Black Duck

Anas rubripes

by Joe Fuller

Updated by Doug Howell

North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission

Classification

Class: Aves

Order: Anseriformes

Average Length

Length: 20 in.–24 in.

Weight: 2.5 lbs.

Food

Food

Various seeds, leaves, stems, roots and tubers of aquatic plants, waste grain, aquatic insects, crustaceans, mussels, and snails.

Breeding

Pair formation usually complete by mid- December. Nesting occurs, March–June; peaks in April. Possibility of 2 clutches.

Young

Clutch size is 7–12 eggs. Incubation period averages 26 days. Young are precocial and reach flight state in 58–63 days.

Life Expectancy

Usually short-lived. About 65% of immature black ducks die during the first year with about a 40% mortality rate each year thereafter.

Range and Distribution

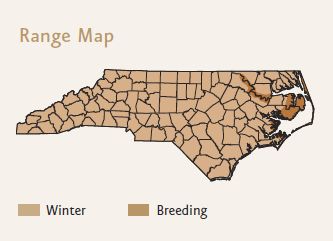

The black duck breeding range in Canada extends from the Maritime Provinces west to eastern Manitoba. In the United States the range extends from the Northeastern states west to about the Mississippi River. The black duck also breeds along the Atlantic Coast as far south as Cape Lookout and Cedar Island, North Carolina.

General Information

The American black duck, along with the wood duck, mallard, teal and others, is a member of the group of ducks called dabbling ducks. Dabbling ducks are recognized by their ability to “jump” vertically from the water when taking flight and by their “dabbling” method of feeding in which they tip up, exposing their rump, when feeding in shallow water. The other group of ducks—the divers—are so named because they dive completely under water to feed. Diving ducks must also “run” across the water before being able to take flight. Examples of diving ducks include canvasbacks, redheads and scaup. In North Carolina, black ducks nest in coastal marshes at low densities and occasionally in beaver ponds. However, black ducks may be seen throughout the state in winter after birds from the North have made their fall migration.

The American black duck, along with the wood duck, mallard, teal and others, is a member of the group of ducks called dabbling ducks. Dabbling ducks are recognized by their ability to “jump” vertically from the water when taking flight and by their “dabbling” method of feeding in which they tip up, exposing their rump, when feeding in shallow water. The other group of ducks—the divers—are so named because they dive completely under water to feed. Diving ducks must also “run” across the water before being able to take flight. Examples of diving ducks include canvasbacks, redheads and scaup. In North Carolina, black ducks nest in coastal marshes at low densities and occasionally in beaver ponds. However, black ducks may be seen throughout the state in winter after birds from the North have made their fall migration.

Description

Aptly named, the black duck is a mottled brown-black duck that is similar in appearance to the more common hen (female) mallard, but it has a much darker body. There is a noticeable contrast between the light brown head and the brown-black body. While in flight, the white underwings provide a striking contrast to the overall black appearance. The black duck is the only common duck in North America where males (drakes) and females (hens) are nearly identical in appearance. Black ducks and mallards interbreed resulting in a variety of plumages. The calls of the drake and hen black duck are nearly identical to the male and female mallard. Calls include a variety of loud quacks, sometimes made in rapid succession. Males are generally less vocal. Black ducks are one of the largest dabbling ducks.

History and Status

History and Status

Historically, the black duck has been considered one of the most highly prized species by waterfowl hunters along the Atlantic Coast. Over time, its winter habitats have been degraded and destroyed by human activities throughout the eastern United States. Corresponding with these changes has been a long-term decline in winter populations of black ducks from approximately 800,000 in the mid-1950s to 300,000 in the 1990s. Their numbers continue to be well below historic levels. Estimates of the numbers of black ducks wintering in North Carolina have also declined over this time.

Habitat and Habits

Throughout its range, the black duck nests in a variety of habitats including marshes, beaver ponds and bogs. Individual nests, however, may be some distance from a wetland area. North Carolina is considered the most southern breeding range for the black duck. Many nests are destroyed due to tidal flooding and predators. The raccoon is the black duck’s prime predator in North Carolina. Black ducks young are precocial—they move about immediately after hatching—and are able to travel long distances to the nearest water. Young stay with the adult hen until they have reached flight stage, about 60 days after hatching.

People Interactions

In winter, black ducks are visible in North Carolina’s coastal marshes. Good places to look for black ducks are the Cedar Island, Pea Island and Mattamuskeet National Wildlife refuges. The birds are very wary, however, and close observation can be difficult. The black duck also remains a favorite quarry for many waterfowlers, but the  species accounts for only about two percent of all ducks harvested in the state. Despite more than 50 years of dedicated research and management efforts, the black duck remains a species of management concern. Continued attention by waterfowl managers and scientists to the status of the black duck will hopefully ensure it remains a species for all to enjoy.

species accounts for only about two percent of all ducks harvested in the state. Despite more than 50 years of dedicated research and management efforts, the black duck remains a species of management concern. Continued attention by waterfowl managers and scientists to the status of the black duck will hopefully ensure it remains a species for all to enjoy.

NCWRC Interaction

Since the 1960s, biologists with the Wildlife Resources Commission have conducted a survey of waterfowl, including black ducks, during January of each year. The survey is conducted from an airplane, primarily in coastal areas of eastern North Carolina, and estimates the numbers of waterfowl that winter in our state. The survey, also known as the Mid-winter Waterfowl Survey, is a cooperative effort with the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, and is conducted in every state in the Atlantic Flyway; an artificial designation which describes the migration paths waterfowl use from their breeding areas to wintering grounds along the Atlantic seaboard. The Mid-winter Waterfowl Survey is the primary population index for the black duck in North America. Based upon this index, black ducks may have declined as much as 60 percent over the last 30 years. Peak numbers of black ducks observed in North Carolina occurred during the late 1970s, with approximately 23,000 counted during the Mid-winter Waterfowl Survey. That number had dwindled to an average of only 7,000 observed during the period from 2001-2005. The black duck also continues to be one of the most studied ducks by biologists in North America.

References

Longco, Jerry R., Daniel G. McAuley, Gary R. Hepp, and Judith M. Rhymer. American Black Duck (Anas rubripes). In The Birds of North America, No 481.

(A. Poole and F. Gill, Eds.).

The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA 2000.

Bellrose, Frank C. Ducks, Geese and Swans of North America (Stackpole Books, 1980).

Bent, Arthur Cleveland. Life Histories of North American Wild Fowl (Dover publications, 1987).

Johnsgard, Paul A. A Guide to North American Waterfowl (Indiana University Press, 1979).

Credits:

Produced 2011 by the Division of Conservation Education; Cay Cross–Editor.

Photos by Steve Maslowski and Derrick Ditchburn Photography.

Illustrations by J.T. Newman.

1 January 2011 | Fuller, Joe; Howell, Doug