Child Labor in Raleigh, North Carolina: Document Based Question

by Steven Hill, BA, MA, NBCT, 2022.

Directions: Using the primary and secondary sources provided, compose an essay that evaluates the motives and realities of child labor in Raleigh, North Carolina’s largest textile mill from the 1890s to the early 1900s.

Background:

Caraleigh is a neighborhood of Raleigh located just over a mile south of the city’s center, inside the I-40 Beltline and a short walk from the State Farmers’ Market; Caraleigh’s origins are in the state’s post-Civil War history, when a “craze” for textile mill building struck North Carolina between the 1880s and the 1910s. There were 60 textile mills in North Carolina in 1885; by 1915, there were 318. Caraleigh’s cotton mill, one of the largest in the state, was described in the 1890s as an integral part of Raleigh’s future growth. Caraleigh originally had three parts: the textile mills, the phosphate and fertilizer plant, and its village, a company- created hamlet for its cotton mill laborers, commonly referred to as operatives. Caraleigh was welcomed in Raleigh as a harbinger of prosperity for a city still struggling to regain its economic composure after defeat in the Civil War. From the start of operations in 1892 until 1930, Caraleigh yielded handsome profits for its investors. In 2022, the original textile buildings are recognized in the National Registry of Historic Landmarks and are home to eighty-four residential, luxury condominium units.

|

Document #1 The July 2, 1899, News and Observer described Caraleigh’s pay scale. This mill gives daily employment to 250 people, and its pay roll amounts to between $1200 and $1500 a week. The employees receive from $1.50 (children) to $9 a week. The foreman—there are three in the mill—get $18 a week. Many young girls earn $6, $7, $8 a week.

News and Observer, July 2, 1899. |

|

Document # 2 A 1918 report about “Child Labor in North Carolina” stated that compulsory education laws required children to attend school for four months but provided no “satisfactory machinery for enforcement,” with enforcement throughout the state left to just one man. On paper at least, the state’s child labor laws protected children from factory work until the “ripe old age of 12.”

Child Welfare in North Carolina: An Inquiry by the National Child Labor Committee for the North Carolina Conference for Social Service, Under the Direction of W.H. Swift (1918) (New York: National Child Labor Committee, 1918), 10–11. |

|

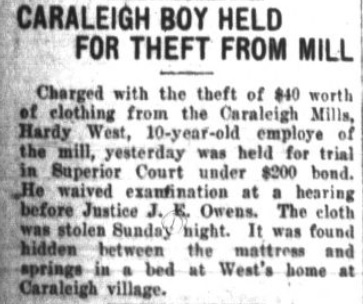

Document # 3

News and Observer, Raleigh, North Carolina, August 20, 1919. |

|

Document # 4 When Caraleigh’s decision-makers decided to plant trees to provide shade around the mill, they avoided “the usual maple or elm” and instead chose pecan trees. Besides shade from the sun, the selection of pecan trees, Caraleigh’s management reasoned, would give occasional nourishment, act as a management tool to control its “doffer boys,” young males ages 12 to 14, and provide a modicum of moral instruction. The doffer boys will be taught to protect and conserve the trees and when the trees begin to bear [nuts] it is Mr. Briggs idea to furnish boxes to the boys in which to stow the nuts where they will be kept until the Christmas holidays and then every child in the village will be given a share of them as a holiday gift from the doffer boys. This is a new idea and one at which some of those who have had trouble in raising young trees around a village will be skeptical, but I believe it will work. My idea is that many a man can be kept out of a crooked path if someone trusts him.”

“Mill Betterment at Caraleigh,” Charlotte News (NC), March 14, 1915. |

|

Document # 5

Caraleigh children in 1923 enjoying the company created playground. (Southern Textile Bulletin, Vol. 25 [June 21, 1923], 152–153). |

|

Document # 6 Besides pecans, Caraleigh’s mill welfare provided age appropriate amusements for its child workers, or “doffer boys.” As reported in 1915, Caraleigh’s management converted the area around the mill into a “playground for the children,” with swings, whirling and “acting poles, where the doffer boys found great amusement when they are not in the mill.”

Dorothy Mitchell, “Mill Village Betterment at Caraleigh,” Charlotte News (NC), March 14, 1915. |

|

Document # 7 W.J. Cash commented that wages in mills were termed a “family wage” because low wages necessitated work from “every member of a family,” father and mother, and “the woman who was about to become a mother,” as well as children.

Wilbur Joseph Cash, The Mind of the South, New York: Vintage Books, 1941. |

|

Document # 8 Child labor laws were passed in several states by 1907, but in other states, such as Alabama, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia, anti–child labor advocates recognized that improvement was needed, because cotton mills “employed the greatest number of children” and thereby represented the “greatest hazard to the growth and development of future generations.”

Alexander McKelway, “The Awakening of the South Against Child Labor,” in “Proceedings of the Third Annual Meeting of the National Child Labor Committee,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 29 (1907), 12. |

|

Document # 9 State newspapers in 1900 reported that “the evil of employing young children” in North Carolina’s cotton mills was “generally recognized,” but that sole blame did not belong to the mill owners; it would be a “gross injustice,” one newspaper argued, to “denounce them for its presence,” for there were many skilled mill workers who refused work “unless their children were also employed.”

“Child Labor in Mills,” News and Observer (Raleigh, NC), Roanoke-Chowan Times (NC), December 20, 1900; Weekly Star (Wilmington, NC), June 23, 1899. |

|

Document # 10 Caraleigh resident Nannie Mae Hussey Smith was interviewed in 1999 and stated that her mother, born in 1900, started in the mill when she was 11 years old and was so short that she “stood on a box to work at the mill.”

Daniel Watkins, “Caraleigh: Raleigh’s Cotton Mill Village.” Thesis/Dissertation. (North Carolina State University: April 9, 2000). |

|

Document #11 In the shadow of the mill, Caraleigh’s playground was said to be “always alive with little children.” A similar story was parroted in the June 1916 Industrial Development and Manufacturers’ Record about Caraleigh’s welfare work that started about “a year or more ago” with the creation of a playground for its “young people” and that these comforts gave “the overseers” assurance, thereafter, that they were “never troubled as to the whereabouts of the doffer boys.”

Lena Rivers Smyth, “Welfare Work in Cotton Mills of North Carolina—Progress Operatives Have Made,” June 15, 1916, Industrial Development and Manufacturers’ Record. C.1 v.69, 1916 (Baltimore: Conway Publications, 1916) cited in Steven A. Hill, “Caraleigh: A History of South Raleigh’s Mill Village Neighborhood, 1891 to Today.” McFarland & Company, Inc. (Jefferson, North Carolina. 2022). |

|

Document #12 Some textile industry experts maintained in the early 1900s that an education was largely unnecessary to become a cotton mill operative. This sentiment was reflected in Raleigh schools opening day attendance report showing both mill villages of Pilot Mills and Caraleigh with the lowest number of students attending in either the white or African American schools in 1907.

Steven A. Hill, “Caraleigh: A History of South Raleigh’s Mill Village Neighborhood, 1891 to Today.” McFarland & Company, Inc. (Jefferson, North Carolina. 2022). |

|

Document #13 Just as the Caraleigh Mills Company provided land for the Caraleigh Baptist Church, they also contributed a rent- free building that contained three rooms for a school of five grades in 1903. In 1904, Caraleigh Mills donated land, as well as $500 for a school building, provided that it obtained a commitment from the School Board of Raleigh Township to provide matching funds.

Steven A. Hill, “Caraleigh: A History of South Raleigh’s Mill Village Neighborhood, 1891 to Today.” McFarland & Company, Inc. (Jefferson, North Carolina. 2022). |

|

Document #14 Caraleigh’s enterprises benefited from cotton farmers’ misfortunes in the late 1800s when prices dramatically fell, causing an exodus of farm families from the countryside who sought work at the textile mills and increasing the demand for commercial fertilizers.

Cathy L. McHugh, “Mill Family: The Labor System in the Southern Cotton Textile Industry, 1880–1915.” (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988) cited in Steven A. Hill, “Caraleigh: A History of South Raleigh’s Mill Village Neighborhood, 1891 to Today.” McFarland & Company, Inc. (Jefferson, North Carolina. 2022). |

|

Document #15 In April of 1908, State School Superintendent James Y. Joyner, newspaper editor Josephus Daniels, and City School Superintendent F.M Harper, spoke at an education rally at Caraleigh, hoping to inspire support for a school tax. Despite the efforts of the noteworthy speakers, most mill workers at Caraleigh were less than enthusiastic about educating their children in the first decade of the new century. The employees of Caraleigh Mills, and incidentally, Pilot Mills, gave the fewest votes in support of taxes for schools, and they “actually cast more votes against the school tax.”

“Raleigh Redeemed by Patriotic Votes,” News and Observer (Raleigh, NC), March 17, 1909, cited in “Caraleigh: A History of South Raleigh’s Mill Village Neighborhood, 1891 to Today.” McFarland & Company, Inc. (Jefferson, North Carolina. 2022). |

3 November 2022 | Hill, Steven