Jones, Thomas H.

By Eric Leder, North Carolina State University, 2013

1806-?

Thomas H. Jones was a self-educated abolitionist, minister, and author who spent much of his early life in Wilmington, North Carolina. Most information about Jones is from his popular autobiography and slave narrative titled Experience and Personal Narrative of Uncle Tom Jones; who was for Forty Years a Slave. Growing up in Wilmington Jones was witness to the auctions of enslaved people and worked for a short stint in one of the most important and largest ports in the south, based alongside the Cape Fear River.

Thomas H. Jones was a self-educated abolitionist, minister, and author who spent much of his early life in Wilmington, North Carolina. Most information about Jones is from his popular autobiography and slave narrative titled Experience and Personal Narrative of Uncle Tom Jones; who was for Forty Years a Slave. Growing up in Wilmington Jones was witness to the auctions of enslaved people and worked for a short stint in one of the most important and largest ports in the south, based alongside the Cape Fear River.

Thomas H. Jones was born enslaved in 1806. His parents and siblings were also enslaved. Although his parents are never named in Jones’s narrative, he does mention his five siblings: Richard, Alexander, Charles, Sarah, and John. Born into plantation life, he was owned by a man named John Hawes. Hawes owned a plantation in New Hanover County, about forty-five miles from Wilmington. The Hawes plantation was home to over fifty enslaved people. In his narrative Jones discusses slavery and oppression, recalling an average work day ranging from first light till dark, as well as the rugged conditions of their labor.

In 1815, Thomas was taken from his family and sold to a man by the name of Mr. Jones. From this enslaver Thomas was given his surname “Jones.” The 45 mile trek from Hawes plantation to the Jones residence in Wilmington was made by foot. It was here that he received his first whipping: “My tasks for that day were neglected. The next morning my master made me strip off my shirt, and then whipped me with the cowhide till the blood ran trickling down upon the floor. My master was very profane, and, with dreadful oaths, he assured me that there was only one way for me to avoid a repetition of this terrible discipline, and that was, to do my tasks every day, sick or well,”

Soon after this incident one of the house cooks died. Jones filled the opening and worked inside, cooking, cleaning, and tending the fire. Mr. Jones’s wife had a particular resentment towards Thomas and after a year insisted that he be placed in the general store, away from her gaze. Working in the general store Thomas met David Codgell, a kind man who sympathized with the tribulations of enslaved people and was able to show Jones that not all people had cruel intentions. Codgell was eventually fired due to his differing treatment of enslaved people and Mr. Jones hired a white boy by the name of James Dixon to work the register.

One day Jones noticed Dixon reading a book and began to question him about learning and education. Jones realized education was the only way to free the mind and thus free the body from the chains of oppression. Tired of being kept ignorant, he procured a spelling book after multiple failures and spent every waking minute of his spare time trying to find meaning in the scribbles.

Around this time Thomas Jones attended a meeting led by Jack Cammon, a freeblack man and Methodist preacher. A newfound religious fervor brought greater urges of freedom, and Jones begged his enslaver to let him join the church. After six months of begging, Mr. Jones allowed Thomas to join the church and take classes; the beginning of a spiritual awakening for Jones.

After the death of his enslaver, Mr. Jones, in 1829, Thomas was sold to Owen Holmes for 435 dollars. It was also at this time that Thomas revisited his birthplace, Hawes Plantation. To his horror he discovered that his family had been separated and his father, brothers, and sisters sold throughout the South. His mother was the only one who remained. At that moment, Thomas decided that he would no longer suffer enslavement and he would do anything and everything in his power to break the chains of his oppression.

While under the ownership of Owen Holmes, Thomas Jones married an enslaved woman named Lucilla Smith. Lucilla, enslaved by a woman names Mrs. Moore, was seventeen years old and an impressive seamstress. Thomas and Lucilla had three children: Lizzie, Annie, and Charlie. For the first time Jones tasted true happiness until Lucilla’s master moved to New Bern taking with him Jones' children and wife. Soon they returned to Wilmington only to board a ship and sail to Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Jones was heartbroken. While waiting for the hopeful return of his family he needed a way to earn a living, and he knew exactly where to look.

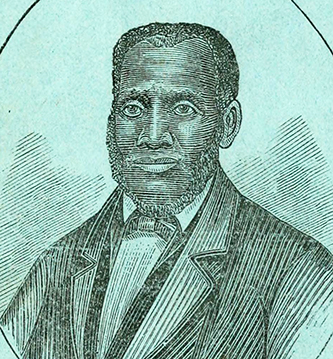

![Engraving of Thomas H. Jones from <i>Experience and personal narrative of Uncle Tom Jones: who was for forty years a slave. Also the surprising adventures of Wild Tom, of the island retreat, a fugitive negro from South Carolina</i>. Boston: J. E. Barwell & Co., Printers. [1854?]. Image from the Internet Archive. Engraving of Thomas H. Jones. He is wearing a top hat, white shirt, and suit coat. He has a smoking pipe in his mouth and curly hair on each side of his face. Text on the image reads "Uncle Tom's Portrait."](/sites/default/files/images_bio/Jones_Thomas_H_Archive_org_experienceand00jones_0009.jpg) Wilmington was an incredibly large and important port city at the time. The Outer Banks islands made it difficult for ships to reach the coast of North Carolina. Ships were able to access Wilmington by sailing up the mouth of the Cape Fear River. Wilmington became a mecca of commerce and people from all over the south came to trade, buy, and sell vast amounts of cotton, tobacco, rice, and enslaved people. By 1840 Wilmington was the largest city in North Carolina and was home to three major railroads. Jones got a job unloading and loading vessels. He was hired for 150 dollars a year and was soon able to rent his own house.

Wilmington was an incredibly large and important port city at the time. The Outer Banks islands made it difficult for ships to reach the coast of North Carolina. Ships were able to access Wilmington by sailing up the mouth of the Cape Fear River. Wilmington became a mecca of commerce and people from all over the south came to trade, buy, and sell vast amounts of cotton, tobacco, rice, and enslaved people. By 1840 Wilmington was the largest city in North Carolina and was home to three major railroads. Jones got a job unloading and loading vessels. He was hired for 150 dollars a year and was soon able to rent his own house.

After four long and solemn years, Jones realized that his beloved Lucilla was never going to return. He married Mary R. Moore, whom he purchased with the aid of a white friend for 350 dollars. This unnamed friend also helped Thomas and Mary purchase a cabin. Since enslaved people were unable to own property, Jones’s friend held the property under his name.

In 1849 Jones was told that men were plotting to take his wife and children back into slavery. Terrified to be separated from his family once again, he concocted a plan to send his wife and children to New York. They enlisted the help of a kind boat captain, and for 25 dollars, Jones sent his family off. The next several months were spent saving up for his own departure from slavery and the south. Fortunately, Jones’s enslaver fell ill and with this opportune moment an escape to New York was made.

After several moves in the North, Thomas Jones and his family finally settled in Salem, Massachusetts. Massachusetts was a forerunner in the abolitionist movement and home to the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. This society hired formerly enslaved people such as Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison as abolitionist orators. Jones became involved with the abolitionist movement and preached often at a Wesleyan Church. In 1852, Jones discovered that he would be able to purchase his eldest son, Edward’s, freedom for the price of 850 dollars. After some problems accumulating funds, Jones decided to write a narrative about his life detailing his trials as an enslaved person. He used his narrative to help raise the funds to purchase his son, although it is unknown whether or not Edwards’s freedom was ever purchased.

Thomas H. Jones became a renowned speaker and activist against slavery. His narrative helped sway popular opinion, while his many speeches reached the masses. By 1859, Jones moved to Worcester, Massachusetts and remained there until 1862. The date of his death is not known, but he lived to see his narrative reprinted with additions in 1885.

References:

“Abolitionist Movement." History Net. Weider History Network. https://www.historynet.com/abolitionist-movement/ (accessed November 12, 2013).

Berkowitz, Claire and Karen Board Moran. "American Anti-Slavery Society." Worcester Women's History Project. https://www.wwhp.org/Resources/Slavery/aass.html (accessed November 12, 2013).

"Declaration of Independence-A Transcription." Charters of Freedom. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs (accessed November 12, 2013).

Tetterton, Beverly. "History of Wilmington." New Hanover County Public Library. Wilmington, N.C.

Melton, Gordon. A Will to Choose: The Origins of African American Methodism. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. 2007. 130. http://books.google.com/books?id=KdZbAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA130#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed November 6, 2013). 130-132

Garrison, William Lloyd. "The Liberator. To the Public." PBS. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4h2928t.html (accessed November 15, 2013).

Schöpf, Johann David, and Alfred J. Morrison (translator). "A slave auction at Wilmington." Travels in the Confederation, 1783-1784 From the German of Johann David Schoepf. New York: Bergman, 1968. Travels in the Confederation, 1783-1784 (accessed November 6, 2013).

Thomas, Jones. Thomas H. Jones Experience and Personal Narrative of Uncle Tom Jones; Who Was for Forty Years a Slave. Also the Surprising Adventures of Wild Tom, of the Island Retreat, a Fugitive Negro from South Carolina.. Boston: H.B. Skinner, 1854? https://archive.org/details/experienceand00jones

"Thomas H. Jones.” Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/jones/support3.html (accessed November 10, 2013).

Image Credits:

[Thomas H. Jones]. Engraving. The experience of Thomas H. Jones, who was a slave for forty-three years. Boston. Printed by Bazin & Chandler. 1862. cover. https://archive.org/details/experienceofthom00jonea/page/n5/mode/2up?view=theater (accessed February 25, 2014).

"Uncle Tom's Portrait." Engraving. Experience and personal narrative of Uncle Tom Jones: who was for forty years a slave. Also the surprising adventures of Wild Tom, of the island retreat, a fugitive negro from South Carolina. Boston: J. E. Barwell & Co., Printers. [1854?]. https://archive.org/details/experienceand00jones/page/n7/mode/2up?view=theater (accessed February 25, 2014).

15 November 2013 | Leder, Eric