Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence

by Ronnie W. Faulkner, 2006; Additional research provided by Kelly Agan; Revised December 2021

See also: Pre-revolutionary Resolves; Mecklenburg Resolves

The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence is the name given to a document that was allegedly produced on May 20, 1775, when the residents of Mecklenburg County declared themselves "free and independent people." The so-called declaration did not surface until 1819, 44 years after the event, when it was published in the Raleigh Register at the behest of U.S. senator Nathaniel Macon. The original document was supposedly destroyed in a fire in 1800, and the published text was reconstructed from memory by John McKnitt Alexander and given to Macon by his son, William Alexander. William Polk, the son of the organizer of the Charlotte meeting, gathered testimony from several elderly men who claimed to have been present. Mecklenburgers immediately started celebrating the date.

The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence is the name given to a document that was allegedly produced on May 20, 1775, when the residents of Mecklenburg County declared themselves "free and independent people." The so-called declaration did not surface until 1819, 44 years after the event, when it was published in the Raleigh Register at the behest of U.S. senator Nathaniel Macon. The original document was supposedly destroyed in a fire in 1800, and the published text was reconstructed from memory by John McKnitt Alexander and given to Macon by his son, William Alexander. William Polk, the son of the organizer of the Charlotte meeting, gathered testimony from several elderly men who claimed to have been present. Mecklenburgers immediately started celebrating the date.

The authenticity of the document was not seriously questioned until the posthumous publication of the works of Thomas Jefferson in 1829. In a letter of July 9, 1819 to John Adams, Jefferson dismissed the Mecklenburg Declaration as a hoax. The North Carolina legislature in 1830-31 was so aroused by this development that it established a committee to investigate. As committee chairman Thomas G. Polk organized the fiftieth anniversary celebration of the Mecklenburg Declaration, it is not surprising that his committee gathered evidence to support the contention that the declaration was authentic.

Despite North Carolina's efforts, a number of scholars outside the state maintained that the Mecklenburg document was a fraud. The ultimate scholarly blow came in 1907 with the publication of William Henry Hoyt's The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: A Study of Evidence Showing That the Alleged Declaration of Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, on May 20th, 1775, Is Spurious. Using the latest methods of scientific history and internal criticism, Hoyt maintained that the evidence was overwhelming that the reconstructed declaration was a misconstruction of the Mecklenburg Resolves of May 31, 1775, which contemporary newspapers proved had been written. Most North Carolinians ignored Hoyt's work, but not Samuel A. Ashe, editor, historian, and descendant of one of the state's most prominent families. The first volume of Ashe's History of North Carolina (1908) presented both sides of the issue but ultimately agreed with the naysayers.

A bitter fight broke out in the North Carolina General Assembly over a bill authorizing the purchase of Ashe's book for the public schools. House Speaker Augustus W. Graham, the son of a governor and descendant of a "signer" of the Mecklenburg Declaration, took the floor and defeated the authorization bill. Opponents of the measure, appealing to patriotism, noted that the date of 20 May was enshrined on the state flag and seal. However, the difference in the old style (Julian) and new style (Gregorian) calendars was 11 days at the time the British adopted the new style in 1752. Even in 1775, Charlotte was in a remote area, and some persons still may have been using the old calendar. This fact could have contributed to a misapplication of the 20 May date to the authentic Mecklenburg Resolves of May 31, 1775.

The negative opinions of professional historians toward the Mecklenburg Declaration, including such luminaries as Stephen B. Weeks, John Spencer Bassett, and R. D. W. Connor, remained intact. The one academic who did support the Mecklenburg legend was Archibald Henderson, a mathematics professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Although modern scholars no longer accept the Mecklenburg Declaration as authentic, it has long been maintained and celebrated. The document emerged at a time when North Carolina was the sleeping and backward "Rip Van Winkle State" and thus appealed to pride by establishing that the state was not only progressive but also in the vanguard of the independence movement.

The Mecklenburg Declaration, a product of legend and patriotic sentiment, most certainly never existed. However, the Mecklenburg Resolves were a very real and bold set of anti-British resolutions adopted by Mecklenburg County residents on May 31, 1775, a full year before the Declaration of Independence was penned at Philadelphia by the Continental Congress. The Mecklenburg Resolves denied the authority of Parliament over the colonies and set up basic tenets of governing.

References:

Mecklenburg Resolves https://www.ncpedia.org/mecklenburg-resolves

Pre-revolutionary Resolves https://www.ncpedia.org/resolves-prerevolutionary

Richard N. Current, "That Other Declaration: May 20, 1775-May 20, 1975," North Carolina Historical Review 54 (April 1977).

Ronnie W. Faulkner, "Samuel A'Court Ashe: North Carolina Redeemer and Historian, 1840-1938" (Ph.D. diss., University of South Carolina, 1983).

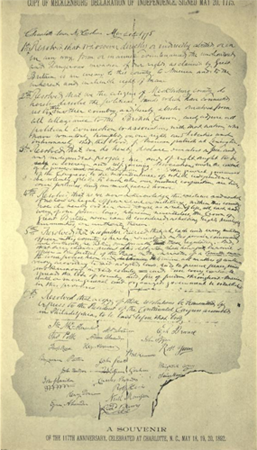

Image credit:

Souvenir depicting the Mecklenburg Declaration from The Mecklenburg declaration of independence : a study of evidence showing that the alleged early declaration of independence by Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, on May 20th, 1775, is spurious. Online at https://archive.org/details/mecklenburgdecla00hoytuoft. Accessed 5/1/2012.

1 January 2006 | Faulkner, Ronnie W.