Resorts

See also: Andrews Geyser; Carolina Hotel; Grove Park Inn; Hot Springs; Outer Banks.

Part i: Introduction; Part ii: Resorts of Western North Carolina; Part iii: Piedmont and Coastal Resorts

Part III: Piedmont and Coastal Resorts

While the Atlantic Coast is undoubtedly a primary attraction for both in-state and out-of-state travelers, the rolling hills and pine forests of the Piedmont and Sandhills regions of North Carolina boast some of the state's finest resorts. In 1890 James Tufts of Boston began construction on the Carolina Hotel in Pinehurst, and soon the town had gained an international reputation as a world-class golf resort with a mild climate. The many other hotels, resorts, and golf courses located in and around Pinehurst and Southern Pines have led to the claim that Moore County is the "Golf Capital of the World." Newer golf resorts, such as Greensboro's Grandover Resort and the Ballantyne Resort in Charlotte, also have begun to attract both out-of-state and in-state visitors to the North Carolina Piedmont.

North Carolina's Atlantic beaches were attracting people at least as far back as the early part of the nineteenth century and soon spawned a major tourism industry, providing the primary economic base for many coastal communities. Hotels are believed to have been at Nags Head since 1838, and some documents indicate that people had gone there in the summer well before the 1830s. Of the distinctive architecture of early twentieth-century coastal resort hotels, one example remains at Nags Head: the First Colony Inn, with its unpainted, weathered shingle siding, third-floor dormers, and bi-level wraparound porches. It was built in 1932 as LeRoy's Seaside Inn and was relocated and refurbished in the 1980s.

Ocracoke appears to have been the first of North Carolina's ocean resorts, though it has remained among the least developed. There are recorded visits to Ocracoke and nearby Portsmouth for sea bathing as early as the 1750s and 1760s, and in 1795 Jonathan Price said of Ocracoke, "this healthy spot is in autumn the resort of many of the inhabitants of the main." The village of Ocracoke is limited in its potential growth by virtue of being surrounded by the lands of one federal park (Cape Hatteras National Seashore) and being next door to another (Cape Lookout National Seashore).

The establishment of the nation's first national seashore in the 1950s (centered at world-famous Cape Hatteras), the construction of the Oregon Inlet bridge, and the paving of a road the length of Hatteras Island in the 1960s opened up more than one-fifth of North Carolina's total ocean shoreline for development. All seven of the Hatteras Island villages were transformed into thriving ocean resorts. Meanwhile, after the construction of a state highway north from Duck to Corolla in the 1970s, the last of the privately owned ocean frontage in the northern part of the state was subjected to development, and the old Currituck Banks area has since experienced a veritable building boom.

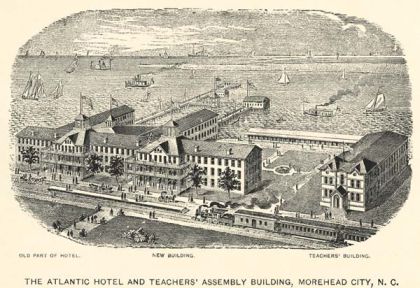

Development of ocean resorts along North Carolina's central coast has followed a pattern similar to that on the northern Outer Banks. There are references from the late colonial period to people at Beaufort going on excursions to the nearby seashore, but the emergence of the area as a widely known resort did not come until the 1850s. At that time, former governor John Motley Morehead, an official of the Atlantic & North Carolina Railroad, announced plans for a large development on Bogue Sound north of Beaufort called Morehead City. On the railroad by 1858, boasting a three-story hotel called Macon House built in 1860, and incorporated as a town in 1861, Morehead City did not gain widespread publicity until 1880, when the 300-room New Atlantic Hotel was built at a choice location overlooking Bogue Sound.

In the 1920s, a bridge was constructed across Bogue Sound to the banks, where a resort town known as Atlantic Beach  was already being developed. A large oceanfront hotel and pavilion at Atlantic Beach served the public through the 1940s, gradually siphoning off tourist business from Morehead City. Following the war, most of the remainder of Bogue Banks was developed, and the ocean resorts of Pine Knoll Shores, Indian Beach, and Emerald Isle now share popularity with Atlantic Beach-though many people continue to refer to the Carteret County resorts as "Morehead." Beginning in the late 1940s, development was initiated farther down the coast on Topsail Island, resulting in still more ocean resorts known as North Topsail Beach, West Onslow Beach, Surf City, and Topsail Beach.

was already being developed. A large oceanfront hotel and pavilion at Atlantic Beach served the public through the 1940s, gradually siphoning off tourist business from Morehead City. Following the war, most of the remainder of Bogue Banks was developed, and the ocean resorts of Pine Knoll Shores, Indian Beach, and Emerald Isle now share popularity with Atlantic Beach-though many people continue to refer to the Carteret County resorts as "Morehead." Beginning in the late 1940s, development was initiated farther down the coast on Topsail Island, resulting in still more ocean resorts known as North Topsail Beach, West Onslow Beach, Surf City, and Topsail Beach.

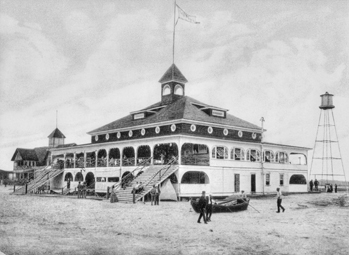

Hugh MacRae, who had previously established the Esseeola Inn and Golf Course at Linville in western North Carolina, was instrumental in the development of the barrier islands east of Wilmington, which up to that time were accessible only by boat. In 1853 the Carolina Yacht Club, said to be the oldest in the United States, built a clubhouse on what was later to become Wrightsville Beach. By 1899, when the town of Wrightsville Beach was incorporated, there were several hotels and more than 50 cottages there. In 1905 MacRae built the centerpiece of Wrightsville, the famous Lumina, a three-story, 25,000-square-foot pavilion on the oceanfront that was elaborately illuminated at night with several thousand incandescent light bulbs. On the second floor was a 50-by-120-foot dance floor surrounded by wide promenades. A balcony for spectators formed the third floor. During the big band era the most outstanding bands in the country played the Lumina, including those headed by Paul Whiteman, Hal Kemp, Guy Lombardo, Cab Calloway, Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, Jimmy Dorsey, and North Carolina's own Kay Kyser. Some claim the shag, a popular dance, was invented at the Lumina.

Although Carolina Beach, located nearer to Cape Fear, was developed at about the same time as Wrightsville Beach, all of the New Hanover County ocean resorts-including Wrightsville Beach, Carolina Beach (sometimes called "Little Coney Island of the South"), and Kure Beach-are often referred to collectively as "Wrightsville." The newest ocean resort in New Hanover and Pender Counties is Figure Eight Island. The remaining Cape Fear-area resorts (some public and some private, gated communities) are in Brunswick County, and most of them-including Sunset Beach, Ocean Isle Beach, Holden Beach, Oak Island, Caswell Beach, and the famously exclusive Bald Head on Smith Island-are the result of post-World War II development activity.

Located across Snow's Cut from Carolina Beach was Sea Breeze, a thriving resort for African Americans built on a 2,500-acre tract previously owned by Black businessman Robert Bruce Freeman. The first building on the beach was constructed in 1922. Eventually Sea Breeze had its own hotels, restaurants, amusement park, fishing pier, and night spots, drawing African Americans from neighboring counties and becoming known as the "National Negro Playground." It became a site for major conventions and housed black musicians during the time when Wilmington hotels would not give rooms to these traveling band members. Both white and Black people were drawn to the music showcased at the resort, which became the basis of beach music. During World War II, Sea Breeze was a popular recreational spot for Black service people from nearby military bases. Destruction by Hurricane Hazel and the demise of segregated beaches put an end to this all-Black beach resort by the early 1970s.

The building of the Blue Ridge Parkway and the creation of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in the mountains, as well as the natural beauty of North Carolina's beaches and national seashores, have continued to make tourism one of the state's major industries. After World War II, the travel industry's focus shifted from wealthy leisure travelers to more mobile, less affluent middle-class tourists. Second-home developments also sprang up in all three resort regions. In the early 2000s, in places such as Beech Mountain, Pinehurst, and Caswell Beach, affluent second-home owners enjoy the same attractions as earlier visitors in exclusive planned communities rather than exclusive hotels. Families visit season after season, often as property owners or cottage renters rather than as hotel guests.

Return to > Part I: Introduction ![]()

References:

Virginia Pou Doughton, Tales of the New Atlantic Hotel, 1880-1933 (1994).

Guion G. Johnson, Ante-Bellum North Carolina: A Social History (1937).

Sydney Nathans, The Quest for Progress: The Way We Lived in North Carolina, 1870-1920 (1983).

Alan D. Watson, Wilmington: Port of North Carolina (1992).

Image Credit:

The Atlantic Hotel, Morehead City, NC. Image courtesy of Documenting the American South, UNC-CH libraries. Available from https://docsouth.unc.edu/true/smith/ill25.html (accessed August 31, 2012).

Lumina, Best Dancing Pavilion on South Atlantic Coast, 1917, Wrightsville Beach, near Wilmington, N.C. Image courtesy of the North Carolina Post Card Collection, UNC-Chapel Hill Libraries. Available from http://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/nc_post/id/2257 (accessed August 31, 2012)

1 January 2006 | Fick, Virginia Gunn; Starnes, Richard D.; Stick, David