Davidson, William Lee

ca. 1746–1 Feb. 1781

William Lee Davidson, Revolutionary War officer, was born in Lancaster County, Pa., the son of George Davidson of County Derry, northern Ireland. When William Lee was about two years old, his father joined the migration from Pennsylvania to the Piedmont of the Carolinas and settled on Davidson's Creek in what is now southern Iredell County, N.C. George Davidson's will, probated in 1760, names as guardians for his children his "trusty and well-beloved Friends" Alexander Osborn and John Brevard, Esquires. These were the most substantial men of the Catawba River section of Rowan (later Iredell) County and they obtained classical educations for their more ambitious sons. William Lee Davidson attended Sugaw Creek Academy near Charlotte at the time when the Reverend Alexander Craighead was pastor and perhaps pedagogue.

William Lee Davidson, Revolutionary War officer, was born in Lancaster County, Pa., the son of George Davidson of County Derry, northern Ireland. When William Lee was about two years old, his father joined the migration from Pennsylvania to the Piedmont of the Carolinas and settled on Davidson's Creek in what is now southern Iredell County, N.C. George Davidson's will, probated in 1760, names as guardians for his children his "trusty and well-beloved Friends" Alexander Osborn and John Brevard, Esquires. These were the most substantial men of the Catawba River section of Rowan (later Iredell) County and they obtained classical educations for their more ambitious sons. William Lee Davidson attended Sugaw Creek Academy near Charlotte at the time when the Reverend Alexander Craighead was pastor and perhaps pedagogue.

On 10 Dec. 1767 the twenty-one-year-old Davidson gave bond of his intention to marry Mary Brevard, daughter of his guardian John Brevard. The Brevards were originally Huguenots who had fled to northern Ireland and thence to America and the North Carolina Piedmont. In many respects, they were the intellectual leaders of Centre Congregation in Rowan County though none of them became ministers. They were also ardent Whigs. At the beginning of the American Revolution John Brevard became an original member of the Salisbury District Committee of Safety, and all eight of his sons saw service as soldiers in the war. One son, Dr. Ephraim Brevard, wrote the famous Mecklenburg Resolves of May 1775.

Many years later, Davidson's Virginia friend and fellow soldier, "Light-Horse Harry" Lee, wrote of him that he was "enamoured of the profession of arms." The spring before his marriage in 1767 he had served as lieutenant in the Rowan militia regiment, which accompanied Governor William Tryon into Cherokee territory to settle a boundary dispute. Less than a decade later, Captain William Davidson was enlisting minutemen to defend the colonies against the king's government. There is evidence that Davidson was prominent in the Charlotte meetings leading to the Mecklenburg Resolves as he owned property in Charlotte. In December 1775 he served as adjutant to Colonel Griffith Rutherford and the Rowan regiment in the "Snow Campaign" against the Tories in upper South Carolina.

North Carolina added four regiments to its Continental line, as distinguished from the state militia, in the spring of 1776. Of the Fourth Regiment, Thomas Polk was made colonel; James Thackston, lieutenant colonel; and William Lee Davidson, major. The North Carolina regiments marched to Wilmington to defend that port from the expected attack by Sir Henry Clinton; when he sailed the British fleet to Charleston, S.C., instead, these troops followed down the coast and participated in the American victory there. It was soon obvious that Major Davidson was a popular officer and, as was observed later, "able to keep up discipline without disgusting the soldiery." Because of his popularity, he was detached from the idle army and sent back to his home territory to recruit.

In the fall of 1777 he marched north with his regiment to join the army of General George Washington. Whether these soldiers arrived in time to fight at Brandywine is not clear, but Davidson was certainly present at the Battle of Germantown and was promoted to lieutenant colonel of the Fifth Regiment, traditionally for gallantry in action in that battle. Then followed the harrowing winter at Valley Forge. Along with his command, Davidson suffered the freezing weather, the inadequate supplies, and the shortage of food. There was some compensation for these trials in the excellent military training given at Valley Forge by Baron von Steuben. Among the friends acquired during this icy ordeal were "Light-Horse Harry" Lee and Daniel Morgan, both to aid later in the defense of the Carolina Piedmont.

In the fall of 1777 he marched north with his regiment to join the army of General George Washington. Whether these soldiers arrived in time to fight at Brandywine is not clear, but Davidson was certainly present at the Battle of Germantown and was promoted to lieutenant colonel of the Fifth Regiment, traditionally for gallantry in action in that battle. Then followed the harrowing winter at Valley Forge. Along with his command, Davidson suffered the freezing weather, the inadequate supplies, and the shortage of food. There was some compensation for these trials in the excellent military training given at Valley Forge by Baron von Steuben. Among the friends acquired during this icy ordeal were "Light-Horse Harry" Lee and Daniel Morgan, both to aid later in the defense of the Carolina Piedmont.

The North Carolina regiments were so depleted that they were consolidated and the supernumerary officers reassigned. Davidson returned to his home state to recruit. His commission was transferred from the Fifth to the Third Regiment and in the fall of 1778 he returned to the north. A year and a half of military duty without much action followed. When the North Carolina troops were again sent south in the autumn of 1779, Davidson asked for and received a well-deserved furlough. He reached his home in Centre Congregation in late December or early January 1780. There were six children in the family, three boys and three girls, and there was to be another son before their young father fought his final battle. By the end of Davidson's leave, his regiment was beleaguered in Charleston and he was unable to join it. The Americans surrendered to Sir Henry Clinton on 12 May 1780, and North Carolina lost practically its entire Continental line.

Left without a command, Davidson offered himself for service in the militia. The brigadier general of Salisbury District was his old comrade-in-arms, Griffith Rutherford, who appointed him second-in-command of the district, which comprised the entire western section of the state. In the battle at Colson's Mill, near the junction of Rocky River and the Pee Dee, Colonel Davidson received a severe wound in the stomach while fighting the Tories. It was said that his Continental uniform made him a conspicuous target. He won the battle but was confined at home for several months. During his convalescence, the Americans were defeated at the Battle of Camden and General Rutherford was captured. Davidson was then promoted to brigadier general of the Salisbury District in Rutherford's place. The British and Tories were infesting the Piedmont of both Carolinas. Cornwallis was determined to take over Charlotte and put an end to the local "rebellion." Davidson and the other commanders kept partisan bands deployed for many miles around. They harassed the British, attacked the Tories, and kept up the spirit of patriot resistance. Cornwallis with his greatly superior force occupied Charlotte in September 1780. Throughout his stay, his men were constantly under sniping attack from the militia. The British could obtain few provisions and get no news from outside. It was this period of the war that gave Charlotte her proud nickname of "The Hornets' Nest."

The colonels mustering their forces to attack Patrick Ferguson in the west petitioned the state for General Davidson or Daniel Morgan to command them. Neither could be spared but the colonels won a signal victory at Kings Mountain. When Cornwallis learned of this, he despaired of success and left Charlotte for Winnsboro with the hornets in hot, but cautious pursuit. The following January, Cornwallis decided once again to invade North Carolina. This time he planned to go around Charlotte and cross the Catawba at one of the numerous fords. General Nathanael Greene, who had been sent by Washington to command the Whig army, relied on Davidson to rouse the militia and delay Cornwallis until the Americans were ready for battle. The militia had been much in the field but at the call of the young commander—Davidson was only thirty-four—they returned with their arms and horses to guard the river. Greene retired northward to Guilford Court House. Davidson stationed men at each of the fords. On the cold morning of 1 Feb. 1781, Cornwallis's army crossed at Cowan's Ford. The Whig picket at the water's edge gave the alarm and Davidson rode at the head of his troops to reinforce them. But it was too late. The British had reached the bank and the young brigadier was shot from his horse by a Tory bullet. The body was recovered late that evening and buried by torchlight the same night in Hopewell Churchyard, there being too many victorious redcoats and Tories in the vicinity to attempt to transport it back to Centre.

Although Cowan's Ford was an American defeat, the British were sufficiently delayed for General Greene to complete his "retreat" that led to the battle at Guilford Court House. The successive failures of Cornwallis culminating at Yorktown are matters of national history. The youthful brigadier had not died in vain.

After the war, Davidson's family moved to land given them for his services in what was then western North Carolina but has since become Tennessee. The county to which they moved was named "Davidson" in his memory and the county seat "Nashville" in honor of the state's other general killed in action. Davidson's widow married Robert Harris of Cabarrus County, N.C., but long outlived him. She died at the home of her daughter Pamela in Logan County, Ky., where her will was probated on 1 Mar. 1824.

Davidson's sons were George Lee, who became a militia general in Iredell County and eventually moved to Alabama; John Alexander, who migrated to Mississippi; Ephraim Brevard, who died in New Madrid, Mo.; and William Lee, born a month before his father's death, who married his cousin Betsy Lee Davidson, settled in Mecklenburg County, and gave the land on which Davidson College—named for his father—is located. The daughters were Jean, wife of Henry Green of Mississippi; Pamela, wife of George McLean of Kentucky; and Margaret, who married the Reverend Finis Ewing and is herself the subject of a small volume called Aunt Peggy (1876).

In 1905 an impressive memorial arch honoring Davidson's Revolutionary War service was erected at Guilford Battle Ground in Guilford County, although Davidson himself was not present at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse. The arch was dismantled in 1937.

References:

Chalmers G. Davidson, "General Davidson's Wallet—183 Years Later," State Magazine 32 (1 Feb. 1965), Piedmont Partisan (1951).

William Lee Davidson Papers (Library, Davidson College, Davidson).

Additional Resources:

Graham, William Alexander. General William Lee Davidson: an address. Greensboro, N.C.: Guilford Battle Ground Co. 1906. https://archive.org/details/generalwilliamle31grah (accessed December 6, 2013).

Lathan, Robert S. "We are Family." Davidson Journal. July 29, 2012. http://davidsonjournal.davidson.edu/index.php/we-are-family/ (accessed December 6, 2013)

"Report by the United States Senate concerning William Lee Davidson's military service in the Revolutionary War." William Saunders, ed., The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Vol. 1. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 159-160. Documenting the American South. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.html/document/csr22-0021 (accessed December 6, 2013).

"William Lee Davidson Arch [Removed], Guilford Courthouse." Commemorative Landscapes of North Carolina. UNC University Libraries. https://docsouth.unc.edu/commland/monument/133/ (accessed December 6, 2013).

Image Credits:

"Greensboro, N.C. Davidson Arch--Guilford Battle Ground." Postcard. Durwood Barbour Collection of North Carolina Postcards (P077). North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives. Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. http://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/nc_post/id/5452 (accessed December 6, 2013).

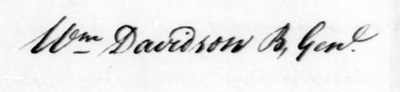

"William Lee Davidson to Horatio Gates, September 26, 1780." Correspondence. George Washington Papers, 1741-1799: Series, General Correspondence, 1697-1799. Library of Congress. http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=mgw4&fileName=gwpage071.db&recNum=333 (accessed December 6, 2013).

1 January 1986 | Davidson, Chalmers G.