Sothel (or Sothell, Southwell), Seth

d. 1693 or 1694

See also: Seth Sothel, Research Branch, NC Office of Archives and History

Seth Sothel (or Sothell, Southwell), Proprietor of Carolina and governor of North Carolina and South Carolina, is first mentioned in extant records in a letter of June 1675 written by Lord Shaftesbury, one of the Carolina Proprietors, to the governor and Council of South Carolina. In the letter, which pertained to plans Sothel had for establishing a settlement in South Carolina, Sothel was described as "a person of considerable estate in England." Nothing is known of his earlier life.

The plan discussed in Shaftesbury's letter was never executed, probably because Sothel found a more promising opportunity in North Carolina. About October 1677 he became one of the Lords Proprietors of the province by purchasing the Proprietorship originally held by Edward Hyde, earl of Clarendon, but then owned by Henry, second earl of Clarendon. About a year after the purchase, arrangements were made for Sothel to go as governor to the northern Carolina colony, then called Albemarle. On the way to Albemarle, however, he was captured by pirates and held in Algiers for ransom.

By September 1681 the pirates had released Sothel, and he was again preparing to go to Albemarle as governor. To that end his fellow Proprietors issued a notice to the two Carolina colonies informing them of Sothel's purchase of the Clarendon share in Carolina, reminding them of a provision in the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina under which the eldest Proprietor residing in the province was to be governor and ordering them to obey Sothel as governor unless an older Proprietor should arrive. The fact that Sothel had a legal right to the governorship under the Fundamental Constitutions, and did not hold office merely through favor of the other Proprietors, no doubt influenced his conduct in office. In effect, it placed Sothel beyond the control of the other Proprietors, making it possible for him to govern without regard for the rights of either the colonists or his fellow Proprietors.

By February 1682/83 Sothel was officiating as governor of Albemarle. Before the end of the year a flow of complaints against him had reached London, making it evident to his fellow Proprietors that he was far from being the "sober discreet gentleman" they had judged him to be. On 14 Dec. 1683 the Proprietary board ordered that a letter be written reprimanding Sothel for failure to follow the instructions he had been given and directing that he provide information on a number of matters. In a letter executing that order the Proprietors complained that Sothel, contrary to their instructions, had named to the Council men who had been prominent in the recent disorders in the colony, that he had ignored their directive to set up a special court to try actions rising from the disorders, that he had not organized a county court as instructed and as required by the Fundamental Constitutions, that he had not allowed the secretary of the colony to have the perquisites of his office but had pocketed them himself, and that he had taken from Colonel Philip Ludwell of Virginia a plantation owned by Ludwell's wife. They directed that Sothel send them the names of the persons he had appointed to the Council, that he inform them of the amount of quitrents he had collected and his disposition of the receipts, and that he give account of his handling of the other matters on which there were complaints. They further directed that he consult the Proprietor John Archdale, who had recently settled in Albemarle, concerning appointments and other matters.

On one point the Proprietors appear to have been misinformed. A county court conforming in large part to the provisions of the Fundamental Constitutions had been in operation since the spring of 1683. Sothel dominated it, however, and used it to provide color of legality for unlawful acts that he committed.

John Archdale may have had a moderating influence on Sothel for a time, but the years he was in the colony were not free from Sothel's oppression. Sothel, however, was in England for several months in 1685 and 1686, during which Archdale served as governor, giving the colonists a period of relief. Whatever influence Archdale had, it ended about 1686, when he returned to England.

Sothel appears to have been moved largely by avarice and to have recognized no deterrent to satisfying his greed. He took what he wanted, whether it was a plantation, a pewter plate, or a piece of lace. He stole from both the rich and powerful and the poor and helpless. On pretext that the land had escheated, he had the Council issue to him a patent for a plantation of 4,000 acres belonging to the wife of Colonel Philip Ludwell, a member of the Virginia Council, who had married the widow of Sir William Berkeley, one of the original Carolina Proprietors. Charging that George Durant, an early settler and influential leader in Albemarle, had committed "an Infammous Libell," Sothel confiscated and appropriated to himself Durant's plantation of 2,000 acres. Pretending that two traders from Barbados were pirates, although their papers were in good order, he confiscated their goods and threw them in prison, where one of them died. He refused to permit the dead trader's will to be probated, taking his property for himself, and when the executor, the prominent Thomas Pollock, undertook to go to London to complain, Sothel threw him in prison. Entrusted with delivery of a box sent to an Albemarle woman by her brother in London, Sothel stole from the box several yards of lace, some cloth, and two guineas. When confronted by the woman's attorney, he admitted the theft and displayed some of the lace sewed to "head-linnen" by his wife, nevertheless refusing to compensate the intended recipient. He kept for himself some pewter plates belonging to the estate of a colonist and forced an orphaned boy, who was under age, to sign a deed conveying to him the boy's plantation. Those who protested against such acts were put in jail and held for long periods without trial, while common criminals escaped punishment by bribing the governor.

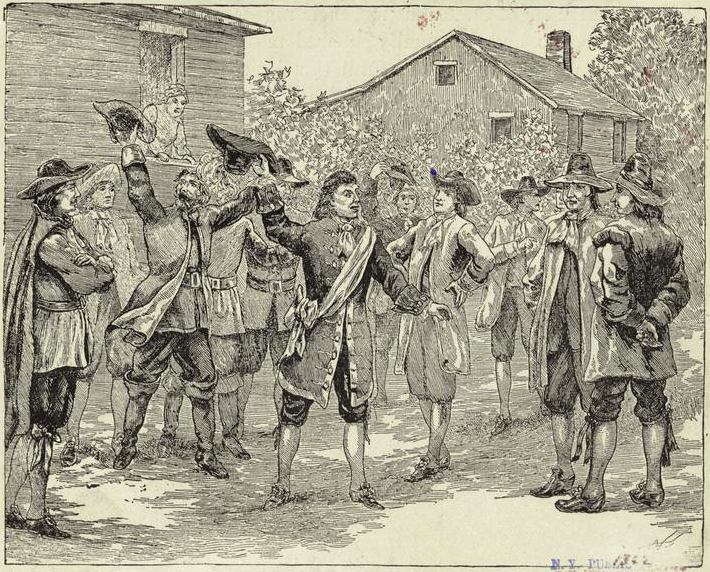

The endurance of the Albemarle inhabitants reached an end in the summer of 1689. About August the colonists rose against Sothel and imprisoned him. They intended to send him to England for trial, but at Sothel's entreaty he was tried by the Albemarle Assembly instead. Finding him guilty of numerous charges, the Assembly banished him from Albemarle for a year and required him to renounce holding office in the colony forever.

News of the events in Albemarle reached London by late fall. On 2 Dec. 1689 the London Proprietors wrote to Sothel expressing hope that the allegations against him were false and that he would be cleared by an investigation they intended to make, but informing him that they were suspending him from the governorship pending such clearance. Three days later they commissioned Colonel Philip Ludwell of Virginia to be governor in Sothel's place.

The Assembly's banishment of Sothel did not take effect immediately. He remained in Albemarle at least through January 1689/90, when he made his will, recorded the deed he had forced George Durant to give him, and no doubt attended to other matters. By summer, however, he arrived in South Carolina, which he had chosen for refuge during his banishment. By 5 Oct. 1690 he had exercised his prerogative under the Fundamental Constitutions and assumed the governorship of the South Carolina colony.

Sothel did not obtain the South Carolina office easily, for the governor, James Colleton, disputed his claim. Supported by a faction that opposed Colleton, however, he took over the office without bloodshed. Almost immediately Sothel displayed the indifference for the rights of his fellow Proprietors that he had demonstrated in Albemarle. Despite instructions from the London Proprietors directing local officials not to hold a parliament until so instructed by them, Sothel called a parliament, which met in December. At his instigation the parliament banished Colleton from the colony and barred him and four others from again holding office. At Sothel's direction, the records and seal of the colony were forcibly taken from the secretary, who was removed from office and imprisoned, although he had been directly appointed by the London Proprietors. Likewise, Council members and lesser officials who had been appointed by the London Proprietors were removed from office and replaced by Sothel's supporters. In effect, Sothel overturned the government authorized by the Proprietary board and set up one controlled by himself alone.

Sothel lost little time before beginning to enrich himself. In February 1690/91 he issued survey warrants for two tracts of land of 12,000 acres each for which he secured patents. He reopened the trade with pirates and personally traded with them. He made changes in the regulations of the Indian trade, changes that are believed to have been directed towards establishing for himself a monopoly of the profitable interior trade, although that was not actually accomplished.

By spring the London Proprietors had learned of Sothel's seizure of the government and his subsequent actions. On 12 May 1691 they wrote reprimanding him for removing their appointees from office, for failing to govern according to their instructions, and for making appointments without their consent. They ordered him to restore the secretary and others he had removed and permit them to perform their duties in peace. They again insisted that he answer to them on the charges brought against him by the Albemarle colonists, which they enumerated, demanding that he go to England at once and answer. Later that month they formally dissented to the act banishing James Colleton, and the following September they informed South Carolina officials of their dissent to all acts passed by the parliament Sothel had called.

Sothel appears to have paid no more attention to the Proprietors remonstrances than he had paid to similar communications while he was in Albemarle. In November 1691 the Proprietors undertook to solve their problem by suspending the Fundamental Constitutions, thereby removing the legal basis for Sothel's claim to office. They also formally suspended Sothel from the governorship and appointed Philip Ludwell, who had succeeded Sothel in Albemarle, to serve as governor of the entire province of Carolina. In a proclamation dated 8 Nov. 1691 they announced their actions to the inhabitants of Carolina.

Ludwell reached South Carolina the following spring and on 13 May 1692 delivered to Sothel a letter from the Proprietors and other documents informing him of his suspension from office. Sothel, however, refused to accept the actions as valid and disputed Ludwell's right to the governorship. Although he appears not to have resorted to bloodshed in his efforts to retain office, Sothel continued for a year or more to claim the governorship. On 11 May 1693 the Proprietors issued a second proclamation announcing their removal of Sothel from office and their suspension of the Fundamental Constitutions. In it they warned the inhabitants not to obey Sothel as governor of Carolina or any part of it.

Sothel no doubt remained in South Carolina until some date after issuance of the Proprietors' proclamation of May 1693, but there are few traces of him in surviving documents after the spring of 1692. There is evidence that he was in Albemarle in November 1693, but he was then in the home of another colonist and may not have been living in Albemarle. His home plantation, which was in Chowan Precinct, appears to have been leased at that time, and there is no contemporary evidence that Sothel lived there after his stay in South Carolina. On the other hand, there is evidence, though not conclusive, that he was a resident of Virginia at the time of his death and that he died and was buried in that colony. His death occurred between an unknown date in November 1693, when he was said to have been at the home of John Porter in Albemarle, and 3 Feb. 1693/94, when his will was proved.

Sothel left no children. He bequeathed most of his Albemarle estate to his wife, Anna, whom he named executrix. Anna, who was the daughter of Belshazzar and Anna Willix of New Hampshire, had been married twice before her marriage to Sothel—first to Robert Riscoe, a master mariner, and second to James Blount, a member of the Albemarle Council. Her marriage to Sothel took place at some date after July 1686, when she probated Blount's will. Sothel also had been married before. In his will he identified an Albemarle inhabitant, Edward Foster, as his father-in-law and bequeathed to Foster a plantation and some cattle. After Sothel's death, Anna married John Lear of Nansemond County, Va., a member of the Virginia Council. She died before May 1695.

Sothel's Albemarle estate was the subject of extensive litigation, in large part because of the irregularities by which much of it had been acquired. Settling the estate was further complicated by Anna's death, which was soon followed by the death of John Lear. The estate eventually was settled by Lear's executors, Lewis Burwell and Thomas Godwin of Virginia.

The ownership of Sothel's share in Carolina also was disputed. Sothel's heirs in England claimed title to the share and sold it to James Bertie early in the eighteenth century. Meanwhile, the surviving Proprietors also claimed the share on the ground that Sothel had left no children, which they claimed caused the share to revert to them under an agreement among the Proprietors. In 1697 they assigned the share to Thomas Amy, who gave it to his daughter Ann and her husband, Nicholas Trott. In 1720 the conflicting claims led to a lawsuit, which resulted in a court order for sale of the share. To establish his title, James Bertie, who had bought the share once, bought it again.

References:

Samuel A. Ashe, ed., Biographical History of North Carolina, vol. 2 (1905).

R. D. W. Connor, History of North Carolina: The Colonial and Revolutionary Periods, 1584–1783 (1919).

J. Bryan Grimes, ed., Abstract of North Carolina Wills (1910) and North Carolina Wills and Inventories (1912).

North Carolina State Archives (Raleigh), various documents, especially British Records (photocopies from British Public Record Office, London), and wills of Richard Humphries (7 Oct. 1688) and Seth Sothel (25 Jan. 1689).

Mattie Erma E. Parker, ed., North Carolina Higher-Court Records, 1670–1696 and 1697–1701 (1968, 1971).

William S. Powell, The Proprietors of Carolina (1963).

Hugh F. Rankin, Upheaval in Albemarle: The Story of Culpeper's Rebellion, 1675–1689 (1962).

W. Noel Sainsbury, ed., Calendar of State Papers, Colonial Series, America and West Indies, vols. 9–15 (1893–1904).

Alexander S. Salley, Jr., ed., Commissions and Instructions from the Lords Proprietors of Carolina to Public Officials of South Carolina, 1685–1715 (1916) and Warrants for Lands in South Carolina, 1672–1711 (1910).

William L. Saunders, ed., Colonial Records of North Carolina, vol. 1 (1886).

Eugene M. Sirmans, Jr., Colonial South Carolina: A Political History, 1663–1763 (1966).

Henry A. M. Smith, The Baronies of South Carolina (1931).

South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine, vols. 8 (1907), 13 (1912), 33 (1932).

Additional Resources:

Mitchell, Robert. "An apology to Seth Sothel." in the Thaddeus Ferree papers #4258, Southern Historical Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. http://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/ead/id/180908 (accessed February 8, 2013).

McCrady, Edward. The history of South Carolina under the proprietary government, 1670-1719. New York: The Macmillan company. 1897. 229-234. https://archive.org/stream/historyofsouthca00mccrrich#page/228/mode/2up (accessed February 8, 2013).

1 January 1994 | Parker, Mattie E. E.