North Carolina State Penitentiary, 1870

by Jason Tomberlin

UNC - North Carolina Collection, 2007.

"This Month in North Carolina History" series. Reprinted with permission.

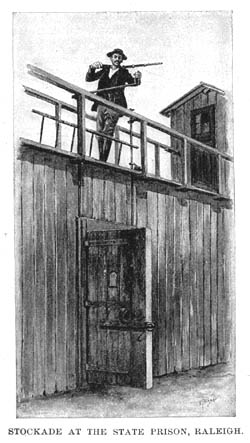

On January 6, 1870, North Carolina’s State Penitentiary accepted its first prisoners, housing them in a temporary log structure that was surrounded by a wooden stockade. Charles Lewis, a twenty-two-year-old African American convicted of robbery in Johnston County, was the first person to be admitted, and his accomplices, Eliza and Nancy Richardson, were the second and third individuals received by the prison and the first women.

On January 6, 1870, North Carolina’s State Penitentiary accepted its first prisoners, housing them in a temporary log structure that was surrounded by a wooden stockade. Charles Lewis, a twenty-two-year-old African American convicted of robbery in Johnston County, was the first person to be admitted, and his accomplices, Eliza and Nancy Richardson, were the second and third individuals received by the prison and the first women.

Prior to 1870, North Carolina, unlike the majority of other states, did not have a central, state-operated prison. Responsibility for housing convicts and administering punishment rested with the counties. As local jails became overcrowded and expenses mounted, public officials began to examine the possibility of opening a state-funded institution to house long-term inmates. In 1846, there was a statewide vote on the desirability of a state penitentiary, but North Carolina’s voters, many of whom still believed in the efficacy of corporal punishment, such as whippings, croppings, and brandings, overwhelmingly disapproved of the plan. Not until mandated by the Reconstruction-era Constitution of 1868 did North Carolina fund and build a state penitentiary.

Operating under this more progressive plan of government, the General Assembly created a penitentiary committee in August 1868 and charged it with selecting a location for the new structure and contracting to have it built. This committee chose and purchased land near Lockville, a community in the Deep River Valley of Chatham County, but the legislature nullified the purchase and began anew after an investigation discovered that the entire process had been fraudulent. The assembly disbanded the original committee and selected a new commission, ordering them to locate the prison near the state capital and giving explicit limitations on acreage and price. The new committee, of which Alfred Dockery was president, purchased about twenty-two acres in southwestern Raleigh. This site had easy access to a railroad line and was adjacent to a stone quarry from which material to build the structure could be removed. With the location chosen, construction of a temporary facility began in late 1869.

Operating under this more progressive plan of government, the General Assembly created a penitentiary committee in August 1868 and charged it with selecting a location for the new structure and contracting to have it built. This committee chose and purchased land near Lockville, a community in the Deep River Valley of Chatham County, but the legislature nullified the purchase and began anew after an investigation discovered that the entire process had been fraudulent. The assembly disbanded the original committee and selected a new commission, ordering them to locate the prison near the state capital and giving explicit limitations on acreage and price. The new committee, of which Alfred Dockery was president, purchased about twenty-two acres in southwestern Raleigh. This site had easy access to a railroad line and was adjacent to a stone quarry from which material to build the structure could be removed. With the location chosen, construction of a temporary facility began in late 1869.

The prison into which Charles Lewis and the other inmates were admitted on January 6, 1870, differed greatly from Central Prison, the modern structure that now occupies the same location. A report submitted by the penitentiary’s assistant architect on November 1, 1870, describes the original wooden edifice as such:

“The Work has been as follows: 2965 ft. Prison Stockade made of long leaf pine poles, hewed on two sides placed close together and set four (4) in the ground, standing fifteen (15) ft. above ground. In which are two (2) large Wagon gates, one (1) Railroad gate, and one small gate for entrance of Persons on foot.

There are twenty (20) Prison Cells, two (2) Hospital Rooms and (2) Rooms for Lockups, all of which are 19x19 ft. square, 8 ft. pitch, built of logs, and sealed with heavy boards on the inside, and all covered with one continuous roof...

There is 850 ft. Railroad Track running in the grounds, and connecting with The N. C. Railroad, also 870 ft. heavy plank stockade enclosing the quarry.”

Believing that the state penitentiary should be self-supporting and that manual labor was beneficial for the prisoners, state officials utilized the readily available and inexpensive inmate work force to construct the permanent buildings, walls, and fences. The process took almost fifteen years and over one million dollars, but in December 1884 the permanent buildings were completed and occupied. The old log cells, which were eventually used as storage bins for animal feed, survived for several more years, with some burning in 1887 and others removed over time.

References and additional resources:

Brown, Roy Melton. “The Growth of a State Program of Public Welfare.” Typescript in North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, ca. 1950.

Murray, Elizabeth Reid. Wake, Capital County of North Carolina. Raleigh, N. C.: Capital County Publishing Company, 1983.

North Carolina. Board of Public Charities. First Annual Report of the Board of Public Charities of North Carolina. February, 1870. Raleigh, N.C.: Printed by Order of the Board, 1870.

North Carolina. Penitentiary Commission. Report of the Penitentiary Commission, to the General Assembly of North Carolina, Made December 8th, 1870. Raleigh, N.C.: The Commission, 1870.

North Carolina. Penitentiary Commission. Rules and By-Laws for the Government & Discipline of the North Carolina Penitentiary During its Management by the Commission. Raleigh, N.C.: M. S. Littlefield, State Printer & Binder, 1869.

Olds, Fred A. “History of the State’s Prison.” The Prison News, vol. I, no. II (November 1926): 4-7.

Image Source:

Ralph, Julian. “Charleston and the Carolinas.” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, No. 536, January 1895.

1 January 2007 | Tomberlin, Jason