Blackbeard the Pirate

by Robert E. Lee, 1986

(ca. 1680–22 Nov. 1718)

Blackbeard, picturesque colonial pirate, is usually said to have been born in Bristol, England. The circumstances of his early life are not known. Pirates rarely wrote about themselves or their families: each hoped to acquire a vast fortune and return to his former home without having tarnished his family name.

Blackbeard, picturesque colonial pirate, is usually said to have been born in Bristol, England. The circumstances of his early life are not known. Pirates rarely wrote about themselves or their families: each hoped to acquire a vast fortune and return to his former home without having tarnished his family name.

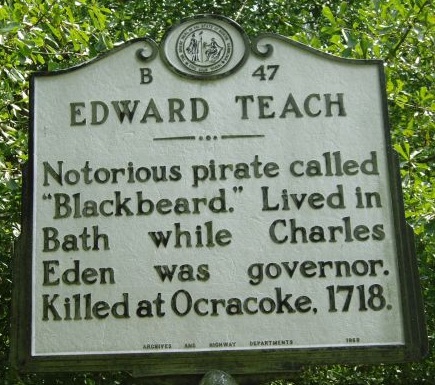

Because pirates tended to adopt one or more fictitious surnames while engaging in piracy, there is no absolute certainty of Blackbeard's real surname. In all the records made during the period in which he was committing his sea robberies, he was identified as either Blackbeard or Edward Teach. Numerous spellings of the latter name include Thatch, Thack, Thatche, and Theach, but Teach is the form most commonly encountered, and most historians have identified him by that name.

Captain Charles Johnson (recently thought to be a pseudonym for Daniel Defoe), a recognized authority on the pirates of the era, states emphatically in A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates, originally published in 1724, that Edward Teach sailed for some time out of Jamaica on the ships of privateers during Queen Anne's War and that "he had often distinguished himself for his uncommon boldness and personal courage."

Sometime in 1716, Teach transferred the base of his operations from Jamaica to New Providence in the Bahama Islands. He served an apprenticeship under Captain Benjamin Hornigold, who was the fiercest and ablest of all pirates regularly operating out of the island of New Providence. Jointly they captured and looted a number of large merchant vessels. Having amassed a sizeable fortune and recognizing that the profitable days of piracy were nearing an end, Hornigold in early 1718 retired from piracy and took up the honest life of a planter on New Providence. He took full advantage of the king's pardon when Woodes Rogers arrived in Nassau on 27 July 1718 as the newly appointed governor of the Bahama Islands.

Teach converted a large French ship, Concord, which he and Captain Hornigold had captured, into a pirate ship of his own design. He renamed her the Queen Anne's Revenge and mounted upon her forty guns. The vessel was eventually manned by a crew of three hundred, some of whom had been members of her crew when she sailed under the French flag.

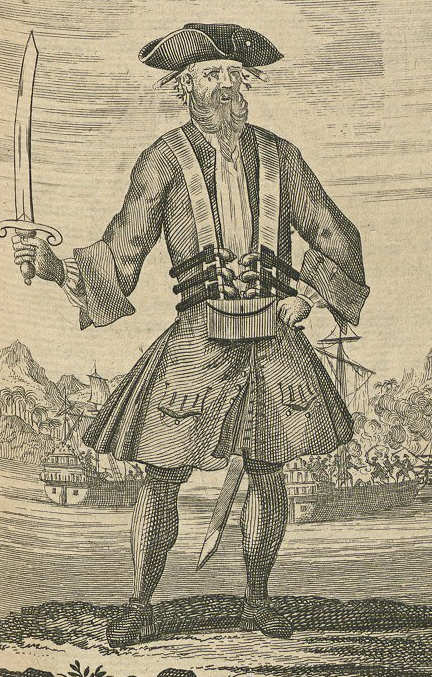

Most men of this period did not wear beards, but Teach discovered that he could grow a coarse, coal-black beard that covered the whole of his face. He allowed his monstrous mane to grow to an extravagant length, and he was accustomed to braiding it into little pigtails, tied with ribbons of various colors. As a finishing touch before a battle, he tucked under the brim of his hat fuses that would burn at the rate of a foot an hour, the curling wisps of smoke from which added to the frightfulness of his appearance. Across his shoulders he wore a sling with two or three pistols hanging in holsters, like a bandolier. In the broad belt strapped around his waist was an assortment of pistols and daggers and an oversized cutlass. Teach's deliberately awesome appearance in battle array had its effect. When ferociously attacked, the crews of many merchant ships surrendered without any pretense of a fight.

Near the end of May 1718, when Teach was at the high tide of his piratical career, he and his armed flotilla of five or six vessels appeared outside the entrance to the harbor of Charleston, S.C., and blockaded the busiest and most important port of the southern colonies. All vessels, inbound or outbound, were stopped and looted. Teach demanded and received from the governor of South Carolina and his council a chest of medicine. Without the firing of a single gun, the pirate king reduced to total submission the proud and militant people of South Carolina.

After the daring and bizarre blockade of Charleston, Teach and his small fleet sailed northward up the Atlantic into what is today commonly known as Beaufort Inlet, for a general disbanding of the crew of about four hundred men: Teach knew the "golden age of piracy" was nearing its end.

Sometime in June 1718, Blackbeard and at least twenty members of his crew passed through Ocracoke Inlet, N.C., entered Pamlico Sound, and headed for the town of Bath on the Pamlico River fifty-odd miles from the Atlantic Ocean. There they received from Governor Charles Eden a "gracious pardon" pursuant to proclamation from the king of England, intended to suppress piracy.

Teach acquired a home in Bath and, for a while, lived the life of a gentleman of leisure. He lost little time in selecting his fourteenth bride, a girl who was about sixteen years of age and the daughter of a Bath County planter. Governor Eden performed the marriage ceremony. But Teach had an unquieted passion for adventure. He was soon, once again, pirating on the high seas and bringing back to Bath his spoils.

Ocracoke Inlet was Blackbeard's favorite anchorage. All oceangoing vessels bound for or leaving settlements in northeastern North Carolina passed through this inlet, and he was usually to be found on the sound side of the southern tip of Ocracoke Island. His crew, however, was greatly reduced; his experienced officers and fighting men of former days were no longer with him, because there was no profit in associating with him unless he was actively engaged in looting vessels. It was here that Blackbeard's death occurred in a famous hand-to-hand battle with Lieutenant Robert Maynard, who had been sent by Governor Alexander Spotswood of Virginia to capture the pirate and his treasure.

Maynard ordered Blackbeard's head severed from his body and suspended from the bowsprit of one of Maynard's two armed vessels. The rest of Blackbeard's corpse was thrown overboard. The head of Blackbeard would be proof irrefutable that Maynard and his crew had slain the pirate chieftain, enabling them to collect the reward of one hundred pounds sterling offered by the Colony of Virginia.

References:

Shirley Carter Hughson, The Carolina Pirates and Colonial Commerce (1894)

Captain Charles Johnson, A General History to the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates, ed. Arthur L. Hayward (1955)

Robert E. Lee, Blackbeard the Pirate (1974)

Hugh F. Rankin, The Golden Age of Piracy (1969).

Additional Resources

ANCHOR: The Life and Death of Blackbeard the Pirate

"Blackbeard's Lost Ship," Secrets of the Dead. directed by David Johnson (April 22, 2009)

The Queen Anne's Revenge Shipwreck Project http://www.qaronline.org/

Bourne, Joel K., Jr. 2006. Blackbeard's shipwreck. National Geographic, July. http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2006/07/blackbeard-shipwreck/bourne-text.

Blackbeard pirate relics, gold found. 2009. National Geographic, March 30. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2009/03/photogalleries/blackbeard-artifacts/

Photos and other images depicting pirates, pirate-related scenes, shipwrecks, etc... from the North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh, NC. https://www.flickr.com/photos/north-carolina-state-archives/sets/72157626379760725/with/5622494324/

Brooks, Baylus C. “‘Born in Jamaica, of Very Creditable Parents’ or ‘A Bristol Man Born’? Excavating the Real Edward Thache, ‘Blackbeard the Pirate.’” The North Carolina Historical Review 92, no. 3 (2015): 235–77. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44113270.

Butler, Lindley S. 2000. Pirates, privateers, and rebel raiders of the Carolina coast. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Rankin, Hugh F. 1960. The pirates of North Carolina. Raleigh: North Carolina Office of Archives & History.

Lawrence, Richard and Mark Wilde-Ramsing. 2001. “In Search of Blackbeard: Historical and Archaeological Research at Shipwreck Site 003BUI,” Southeastern Geology. February. http://qaronline.org/Portals/5/Documents/lawrencescreen.pdf

"Blackbeard the pirate," Our State, August 1997. https://digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/our-state/979742?item=979884

1 January 1986 | Lee, Robert E.