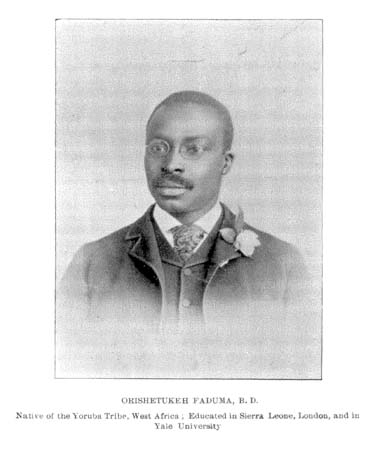

Faduma, Orishatukeh

by Gustav H. K. Deveneaux

(1855–25 Jan. 1946)

Orishatukeh Faduma, teacher and minister, was born in Guyana, South America (formerly British Guiana), to John and Omolofi Faduma, freed African slaves from Yorubaland (now in southwestern Nigeria, West Africa). The inhabitants of this region, the Yoruba, constitute one of the largest ethnic groups in the country. British antislavery policies provided for the settlement in Sierra Leone of Africans taken from British and other slavers whose countries had reciprocal right of search and equipment treaties with Britain. Sierra Leone, a British colony, had been established in West Africa in 1787 for the settlement of such recaptives. In this way, Faduma and his parents were settled in Freetown, the seat of administration in the colony.

Orishatukeh Faduma, teacher and minister, was born in Guyana, South America (formerly British Guiana), to John and Omolofi Faduma, freed African slaves from Yorubaland (now in southwestern Nigeria, West Africa). The inhabitants of this region, the Yoruba, constitute one of the largest ethnic groups in the country. British antislavery policies provided for the settlement in Sierra Leone of Africans taken from British and other slavers whose countries had reciprocal right of search and equipment treaties with Britain. Sierra Leone, a British colony, had been established in West Africa in 1787 for the settlement of such recaptives. In this way, Faduma and his parents were settled in Freetown, the seat of administration in the colony.

Apparently like many other children, Faduma was baptized a Christian upon arrival in Sierra Leone. In keeping with the missionary attitudes then of regarding African names as "heathenish," he was given the name of William James Davies, by which he was known until 1887 when he changed it to Orishatukeh Faduma. Also like the children of other captives, he attended school in one of the leading Christian establishments in the colony, the Methodist Boys High School. Upon graduation from the school, where he must have excelled, he continued his education at the Wesleyan (now Queens) College, Taunton, England, from 1882 to 1883. He then attended London University, where in 1885 he became the first Sierra Leonean to obtain the intermediate bachelor of arts degree.

After completing his studies in England, Faduma returned to Sierra Leone where he probably taught school for a time. It is definite that between 1885 and 1891 he was senior master at the Methodist Boys High School, a position he would not have obtained without prior teaching experience. In 1891 he came to the United States for additional education, one of the few Africans to do so. Receiving a scholarship of $400 to study the philosophy of religion, he continued his postgraduate work at Yale Divinity School (1894–95) where he was awarded a B.D. in 1895. Afterward he remained in the United States.

Sometime between 1891 and 1895 Faduma became affiliated with the American Missionary Association, whose major focus was the evangelization of African-Americans and Africans. During this period he also became more closely associated with the African Methodist Episcopal church and most likely was ordained a minister. From 1895 to 1914, he was principal and pastor-in-charge of Peabody Academy, Troy, N.C., which was established in 1880 for the education of blacks—mostly as teachers to work in the rural areas of North Carolina under the sponsorship of the American Missionary Association. In the early 1900s the academy had four teachers, excluding the principal, two of whom were Henrietta Faduma, Faduma's wife, and Ada Smitherman, a resident of Troy.

Returning to Sierra Leone, Faduma was principal of the United Methodist Collegiate School from 1916 to 1918. Between 1918 and 1923, he served as inspector of schools in the colony, as well as instructor and officer-in-charge of the Model School. Somewhat equivalent to the American junior high school, the Model School prepared pupils for entry into the job market provided they failed to continue their education through the high school level.

In 1924 he returned to the United States and continued teaching in North Carolina until 1939. He served as assistant principal and instructor in Latin, ancient and modern history, and English literature at Lincoln Academy, Kings Mountain. Both Peabody Academy and Lincoln Academy afterwards closed. Upon his retirement, Faduma took up another assignment at the Virginia Theological Seminary and College, Lynchburg.

Faduma's life was not confined to teaching, however. He was very much a public man influenced by the contemporary trends of politics, religion, culture, race, and social relations not only in Sierra Leone, but also in Africa at large and the United States. Thus, soon after his return from England in 1887 he joined with other public-spirited members of the Freetown community in Sierra Leone—such as Dr. Edward Blyden and A. E. Tobuku-Metzger—to form what was known as the Dress Reform Society. The aim of the society was to foster the wearing of African robes, which were more suited to the climate in Sierra Leone and reflected the African cultural heritage, rather than the "Victorian" coat and tie imposed on the westernized settlers or Creoles.

It was at this time that Faduma, who had previously been known as William Davies, changed his name. He adopted Orishatukeh, derived from the Yoruban deity Orisha, and Faduma, his father's name. Many other Creoles also either dropped their baptismal English names for African ones or appended African names to the ones they already had. This cultural movement was part of the Creole response to British racial and cultural paternalism, as well as an attempt to return to their African roots in the hope of finding security in the dilemmas resulting from straddling both the African and European worlds. Much later, Professor Faduma, as he was commonly called, continued to display his political awareness and breadth of vision. In 1923, he was a delegate to the second meeting of the National Congress of British West Africa held in Freetown. The formation of the congress was the earliest effort by West African nationalists from the middle class to create a movement to pressure the British government for political concessions.

In the United States, Faduma also was active publicly. In 1892, he was a member of the Advisory Council in African Ethnology at the World's Exposition in Chicago. Two years later he was Yale's delegate to the Inter-Seminary Missionary Alliance at Rochester, N.Y., and contributed a paper entitled "Industrial Missions in Africa." In 1895 he delivered two papers on Yoruban religion and missionary work in Africa at a missionary congress on Africa, which was held simultaneously with the Cotton States Exposition in Atlanta. It was at the exposition that Booker T. Washington made his important "Atlanta Compromise" speech and established himself as the spokesman for African-Americans in the United States. Other important black leaders attending the congress were Bishop Henry McNeil Turner, Dr. Alexander Crummell, and T. Thomas Fortune.

Faduma was a member of the American Negro Academy, based in Washington, D.C., which had been established by African-American intellectuals as a forum to express their views on important issues affecting blacks. He was the only African to address the academy, where he spoke in 1904 on "The Defects of the Negro Church." He is also said to have addressed the North Carolina Teachers Association on "The Value of Education in Civic Life" in June 1915.

In September 1895 Faduma married Henrietta Adams, a teacher at Peabody Academy. They had two children: Jowo (b. 1902), who was given a Yoruban name; and Dubois (b. 1922), who was presumably named after W. E. B. Dubois, the great African-American leader and Pan-Africanist.

There can be no doubt that Faduma enjoyed public speaking. On several occasions he went on lecture tours in both the United States and Sierra Leone. Apparently because of these and other activities he was awarded an honorary doctorate of philosophy by Livingstone College in Salisbury, N.C.

Faduma seems to have been a prolific writer as well as a poet. Among his published works were "A Ballad on Egbaland," in AME Church Review (July 1888); "In Memoriam, The Centenary of Sierra Leone," in AME Church Review (October 1889); "Thoughts for the Times, or the New Theology," in AME Church Review (October 1890); "Africa or the Dark Continent," in AME Church Review (July 1892); "Religious Beliefs of the Yoruba People in West Africa" and "Success and Drawbacks of Missionary Work in Africa by an Eye-Witness," in Africa and the American Negro , J. W. E. Bowen, ed. (1896); "Africa the Unknown," in Mission Herald (November-December 1939); "An African Background: My Pagan Origin and Inheritance," in Mission Herald (September-October 1940); and "The Defects of the Negro Church," Occasional Paper No. 8 (1904).

The speeches, writings, and activities of Orishatukeh Faduma reveal that during his long life he was endowed with a keen wit, tremendous energy, and a passion for involvement in political and social issues. His prime avocation undoubtedly was education, and it may be assumed he was successful at it judging by the number of significant and responsible teaching positions he held. He was also a devoted Christian minister. It appears that as he grew older, however, he became more aware of the contradictions regarding race and contempt for black and African values within the Christian ministry. This consciousness led him to greater flexibility. As he once observed, "No foreign missionary introduces God to the African. What he does is to interpret God to him. I owe much in my foundation to my pagan inheritance of qualities which are needed and exalted in Christianity. For these things, I thank God. Of what can I boast?" Again he observed, "The aim and purpose of Christian missions is not to Anglicize, Americanize, or Germanize the world, but to Christianize it."

Professor Faduma's experiences in America at the height of "Jim Crowism" particularly sharpened his consciousness of race. Although he must have developed emotional mechanisms of accommodation to racial segregation, he inveighed against the system and sought to elevate the black man—not only in his work but also by his thoughts and writings. He was nevertheless a temperate man not given to bitter fulminations, but caustic wit. Consider, for example, his reminiscence of a "racial" episode in the United States. "I was once asked in a public lecture whether my father was a white man anywhere, the gentleman who questioned me said. 'What am I?' 'A pink man' I replied. As if to clarify his question, he said 'I mean whether you have white blood in you.' 'White blood?' said I. 'All Bloods I have seen are red, not white. I have seen men of different colors, but not different-color bloods.'"

Faduma also emerges as one of the earliest African nationalists and Pan-African patriots. From his earliest days as a founding member of the Dress Reform Society in Freetown, Sierra Leone, and his membership in the National Congress of British West Africa to his relentless devotion to the education and elevation of African-Americans, especially in North Carolina and Virginia, his pride and faith in the potential of his African heritage remain outstanding. Further research into the life and times of Faduma may yet reveal the many dimensions of his life and establish him as an important figure in African and African-American history.

References:

Charles Alexander, One Hundred Distinguished Leaders (1899)

Edward W. Blyden, Pan-Negro Patriot, 1832–1912 (1967)

William H. Ferris, The African Abroad, or His Evolution in Western Civilization, Tracing His Development under Caucasion Milieu (1913)

Christopher Fyfe, A History of Sierra Leone (1968)

Who's Who in Colored America (1940)

Image credits

Orishatukeh Faduma. J. W. E. Bowen, Africa and the American Negro: Addresses and Proceedings of the Congress on Africa (1895). Courtesy of DocSouth.

1 January 1986 | Deveneaux, Gustav H. K.