Hunter, James

Ca. 1735–Ca. 1783

See also: Regulator Movement (from the Encyclopedia of North Carolina)

James Hunter, leader of the Regulator movement, was born of Scot-Irish ancestry probably in Pennsylvania. Tradition has him the son of James, Sr., but his mother was the former "widow Ann Hunter" who in 1755 purchased land of her son-in-law, Gilbert Strayhorn, in Orange County. Strayhorn family records pertaining to New Hope Presbyterian Church, Orange County, note that James Hunter moved to the county as a young man, possibly some years before his mother bought her land there. On 11 May 1757 he was granted 200 acres of land in what was then western Orange County, and in January 1779 he and James Low acquired 640 additional acres adjacent to or near the first grant.

James Hunter, leader of the Regulator movement, was born of Scot-Irish ancestry probably in Pennsylvania. Tradition has him the son of James, Sr., but his mother was the former "widow Ann Hunter" who in 1755 purchased land of her son-in-law, Gilbert Strayhorn, in Orange County. Strayhorn family records pertaining to New Hope Presbyterian Church, Orange County, note that James Hunter moved to the county as a young man, possibly some years before his mother bought her land there. On 11 May 1757 he was granted 200 acres of land in what was then western Orange County, and in January 1779 he and James Low acquired 640 additional acres adjacent to or near the first grant.

Court minutes of the county indicate that Hunter was active in local affairs and seemed to be better educated than the average person. He early assumed a position of leadership in the Regulator movement through which many people in the backcountry sought to gain more influence in local government. Hunter is credited with having helped to draft some of the Regulator "Advertisements" and petitions. Such petitions to Governor William Tryon seem to have had no effect, and the Regulators believed that their chief opponent was Edmund Fanning, register of deeds and superior court judge in Orange County and holder of other offices. He was a close friend of Governor Tryon.

At each step of the Regulator movement, Hunter took an active part. His signature appears on most of the petitions, and he was entrusted to deliver several of them. In March 1768, after peaceful measures had failed, the Regulators warned officials that future taxes would be collected at the risk of the sheriff's life. The warning was ignored, and a farmer's mare, with saddle and bridle, was seized for unpaid taxes. In response, a party of Regulators proceeded to Hillsborough, the county seat, and "rescued" the mare; they also fired some shots into Colonel Fanning's house. Further incidents occurred after Regulator leaders Herman Husband and William Butler were arrested and charged with inciting the people to riot.

Petitions to the governor failed to bring relief. Although Regulators were elected to the Assembly, they were unable to secure passage of desired legislation—in part, because members of the Assembly were beginning to support early steps that led to the American Revolution. As a result the governor dissolved the legislature. The courts, it seemed, also failed the Regulators when the judges found Fanning guilty of charges of corruption but failed to punish him. When the Regulators broke up one session of court and threatened to repeat such action, the governor called out the militia to restore order in Orange County and elsewhere in the backcountry.

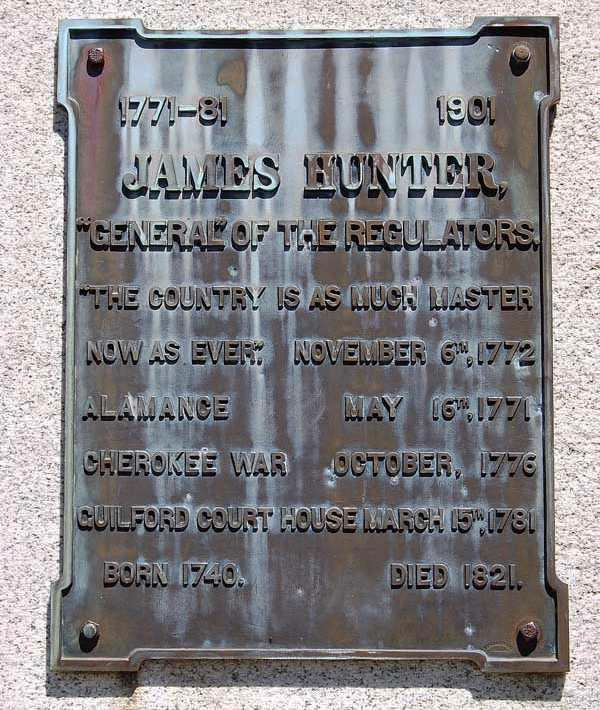

Matters came to a head in the spring of 1771, when Tryon led the militia of some 1,400 men to a site west of Hillsborough where a large number of Regulators were encamped. The Regulators requested a conference with the governor, but he refused as long as they were armed. He would, however, confer with a delegation if the remainder laid down their weapons, and he gave them one hour to reply. At the end of the hour, the governor sent a messenger to seek their answer and to tell them that if they did not respond he would order his force to fire. About this time a few of the Regulator leaders, including the Quaker Herman Husband, left the scene. James Hunter was asked to assume leadership, but he refused with the traditional response that "they were all free men and every one must command himself." Hunter, nevertheless, somehow came to be called "the general of the Regulation."

Matters came to a head in the spring of 1771, when Tryon led the militia of some 1,400 men to a site west of Hillsborough where a large number of Regulators were encamped. The Regulators requested a conference with the governor, but he refused as long as they were armed. He would, however, confer with a delegation if the remainder laid down their weapons, and he gave them one hour to reply. At the end of the hour, the governor sent a messenger to seek their answer and to tell them that if they did not respond he would order his force to fire. About this time a few of the Regulator leaders, including the Quaker Herman Husband, left the scene. James Hunter was asked to assume leadership, but he refused with the traditional response that "they were all free men and every one must command himself." Hunter, nevertheless, somehow came to be called "the general of the Regulation."

At the Battle of Alamance, which followed, the absence of a military leader made the outcome of the engagement predictable in favor of Tryon's militia. Twenty Regulators were killed, many were wounded, and twelve were captured, six of whom were later hanged. Tryon's casualties were nine killed and some sixty wounded.

Even though Hunter did not regard himself as a military leader, he was a natural leader among his friends and neighbors. After the Battle of Alamance, Governor Tryon issued a proclamation outlawing him and the other Regulator leaders. Almost a year later, after Tryon had become governor of New York and Josiah Martin had become governor of North Carolina, Hunter was permitted to return to his home and family. Petitions for his pardon, submitted to the governor by his friends and neighbors, show the esteem in which he was held.

The Regulator effort cost Hunter dearly. His plantation was laid waste by Tryon after the battle. As a condition of pardon, he was obliged to take an oath of allegiance to the Crown. Then as events proceeded swiftly into the conflict between America and Great Britain, a new test came. Because he could not in good conscience repudiate his solemn oath, he found himself classified as a Tory. In February 1776, Governor Martin issued a call to the Regulators and Scottish Highlanders to "raise the King's Standard" at Cross Creek on the Cape Fear to repel the "Rebels." Those Regulators called out from the newly formed Guilford County, in which his property now lay, included James Hunter and his brother-in-law, Robert Fields, and Robert's brothers, William and Jeremiah. They all participated in the Battle of Moores Creek, a Patriot victory. The Fields brothers were captured, as was James Low, the man who entered for the land grant with Hunter and who is believed to have been his brother-in-law. Although not apprehended at the scene of the battle, Hunter was subsequently arrested. A few months later he was paroled after taking the oath of allegiance to the new government.

The Regulator effort cost Hunter dearly. His plantation was laid waste by Tryon after the battle. As a condition of pardon, he was obliged to take an oath of allegiance to the Crown. Then as events proceeded swiftly into the conflict between America and Great Britain, a new test came. Because he could not in good conscience repudiate his solemn oath, he found himself classified as a Tory. In February 1776, Governor Martin issued a call to the Regulators and Scottish Highlanders to "raise the King's Standard" at Cross Creek on the Cape Fear to repel the "Rebels." Those Regulators called out from the newly formed Guilford County, in which his property now lay, included James Hunter and his brother-in-law, Robert Fields, and Robert's brothers, William and Jeremiah. They all participated in the Battle of Moores Creek, a Patriot victory. The Fields brothers were captured, as was James Low, the man who entered for the land grant with Hunter and who is believed to have been his brother-in-law. Although not apprehended at the scene of the battle, Hunter was subsequently arrested. A few months later he was paroled after taking the oath of allegiance to the new government.

Afterwards it became necessary for Hunter to mortgage his property. It also appears that his health was broken, and he died sometime between October 1779 and February 1783 when his widow Mary was given administration of his estate.

Although no record survives of the marriage of the Regulator, James Hunter, to Mary Walker, the will of Samuel Walker, dated 1773 and probated in 1783, names his sons-in-law, James Hunter and Robert Fields, as his executors. Genealogical research suggests that Hunter's five children were Martha (m. Aaron Hill), Samuel (m. Lydia Deviney), Marion (m. Alexander Strain), Mary (m. William Strayhorn), and James, Jr. (m. Margaret Phipps). James, Jr., and Samuel later moved to Clinton County, Ill., whereas their descendants moved to Texas and the Far West.

References:

James W. Albright, History of Greensboro (1904).

Vearl G. Alger, "The Case for James Hunter of Stinking Quarter and Sandy Creek: Regulator Leader, 1765–1771," North Carolina Genealogical Society Journal 3 (1977).

E. W. Caruthers, A Sketch of the Life and Character of the Rev. David Caldwell (1842).

D. I. Craig, Historical Sketch of New Hope Church in Orange County, N.C. (1891).

Granville Land Grants, Records of Guilford, Orange, and Randolph Counties (North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh).

Walter M. Hunter, The Hunters of Bedford County, Virginia (1972).

Hugh T. Lefler and Paul W. Wager, eds., History of Orange County, 1752–1952 (1953).

William S. Powell, James K. Huhta, and Thomas J. Farnham, eds., The Regulators of North Carolina: A Documentary History, 1759–1776 (1971).

William L. Saunders, ed., Colonial Records of North Carolina, vols. 7–10 (1890).

Sallie W. Stockard, History of Guilford County (1902).

Additional Resources:

Caruthers, E. W. (Eli Washington). Revolutionary incidents: and sketches of character, chiefly in the "Old North state". Philadelphia: Hayes & Zell. 1854. https://archive.org/details/revolutionaryinc00caru (accessed February 4, 2014).

Image Credits:

"[James Hunter] Monument [Plaque], Accession #: S.HS.2008.45.1." Photograph. North Carolina Historic Sites. (accessed February 4, 2014).

"Photograph [of engraving of Gov. Tryon and the Regulators in one of their stormy meetings], Accession #: H.1949.38.1." 1949. North Carolina Museum of History. (accessed February 4, 2014).

1 January 1988 | Alger, Vearl G.