Jones, Joseph Seawell

ca. 1806–20 Feb. 1855

Joseph Seawell Jones, historian and humbug, was born in Warren County, the son of Edward J. and Elizabeth Seawell Jones. His father, a planter, owned a 2,000-acre tract near Shocco Springs; his mother was a sister of Judge Henry Seawell of the North Carolina Supreme Court and a niece of Nathaniel Macon. After attending various academies in Warren and Franklin counties, Jones entered The University of North Carolina in 1824. It was probably during his college days that he became known as "Shocco" Jones—to distinguish him from other students who had the same familiar surname.

Joseph Seawell Jones, historian and humbug, was born in Warren County, the son of Edward J. and Elizabeth Seawell Jones. His father, a planter, owned a 2,000-acre tract near Shocco Springs; his mother was a sister of Judge Henry Seawell of the North Carolina Supreme Court and a niece of Nathaniel Macon. After attending various academies in Warren and Franklin counties, Jones entered The University of North Carolina in 1824. It was probably during his college days that he became known as "Shocco" Jones—to distinguish him from other students who had the same familiar surname.

At Chapel Hill Jones exhibited an inclination towards unconventional behavior that would characterize the remainder of his life. His refusal to apply himself to studies he disliked and his frequent absences from classes and chapel led to his dismissal in 1826. From 1829 to 1832 he intermittently attended the Harvard Law School, which awarded him the LL.B. degree in 1833. Although he had previously obtained a license to practice in the county courts of North Carolina, he apparently never made a serious effort to engage in the legal profession.

Instead, Jones devoted his attention for the next several years to two fields of endeavor: the writing of North Carolina history and "enjoying the fun of hoaxing people." His first book, A Defence of the Revolutionary History of the State of North Carolina from the Aspersions of Mr. Jefferson (1834), gave special prominence to a sympathetic treatment of the Regulator movement, a defense of the "Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence," and a vindication of the character of William Hooper. Although for the most part Jones's book measured up to the established standards of the day, it also revealed that facet of his personality for which he became famous—his "propensity to hoax and play upon the credulity of the public." Into his narrative he casually introduced "Miss Esther Wake," the supposed sister-in-law of Governor William Tryon, in whose honor he maintained Wake County was named. She was one of the earliest hoaxes that Jones imposed upon his fellowman. He apparently also originated the phrase, "Old North State."

In January 1834, the first of two celebrated "duels" involving Jones attracted the public eye. He allegedly participated in an affair of honor at Pawtucket, R.I., with a certain "Mr. Hooper," who had questioned the "delicate reputation of a Lady." Jones responded to a proclamation for his arrest issued by the governor of Rhode Island with a counterproclamation—to which he affixed the "Great Seal of Shocco"—offering a reward of tar and feathers for the governor's apprehension. He also avowed that the next duel he fought would be across the borders of Rhode Island, "which is not more than the usual distance between the parties in such cases convened." If a duel with "Mr. Hooper" took place, it was doubtless staged to publicize Jones's book.

He apparently planned a second and more ambitious historical work entitled "A Picturesque History of North Carolina," to be embellished with expensive engravings, but abandoned the enterprise because of its excessive cost. In January 1836, a correspondent of the Richmond Enquirer wrote that he had seen such a work but questioned that it was published in Raleigh as claimed. Jones undoubtedly was the author of this letter as well as a rejoinding one testifying to the domestic production of such a handsome volume. No such book was in fact published. In the meantime he wrote a series of articles on North Carolina history which appeared in the New-York Mirror, the Raleigh Register, and other journals. These essays—perhaps originally intended for "A Picturesque History"—were collected in a small volume, Memorials of North Carolina, published in 1838.

Jones engineered his two most widely publicized hoaxes in 1839. In April, according to accounts in the Norfolk press, he killed a "Mr. H. Wright Wilson of New York" in an affair that took place near the Dismal Swamp Canal. Although his well-known "love of fun, frolick and hoax" raised doubts about the authenticity of this reported duel, the evidence produced that such an event had taken place appeared incontrovertible. It was not until five months later that a man whom Jones had duped into corroborating his account of the duel reluctantly concluded that "evidence" had been skillfully fabricated to make it appear that a fatal meeting had taken place.

Meanwhile, Jones had embarked on the most spectacular adventure of his career. A few weeks before his Dismal Swamp caper, he journeyed to Mississippi, a state hard hit by the economic recession of the late 1830s. Carrying impressive parcels labeled "Cape Fear Money" and "Public Documents," he let it be known that he had come to the state in a dual capacity: as an agent of the Bank of Cape Fear of Wilmington, he was seeking investment opportunities; and as an agent of the U.S. Treasury Department, he intended to compel Mississippi's two "pet banks" to repay the government deposits entrusted to them prior to the panic of 1837. He immediately became the most respected and feared man in the state. Wined and dined by applicants for loans, he was able to persuade the directors of one hard-pressed Columbus bank to name his stepfather, James Gordon, their new president. Many prominent Mississippians, including former Governor Hiram Runnels and Seargent S. Prentiss, then a candidate for the U.S. Senate, fell for his ruse. Not until October was it discovered that his parcel of "Cape Fear Money" contained nothing but blank pieces of paper and his "Public Documents" were actually old newspapers.

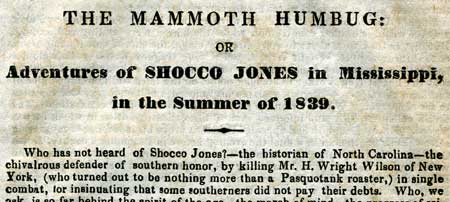

Though publication in 1840 of a widely reprinted newspaper account of "The Mammoth Humbug, or the Adventures of Shocco Jones in Mississippi, in the Summer of 1839" by Francis Leech brought Jones a measure of nationwide fame, he spent his remaining life in virtual obscurity. After leaving Mississippi for a while, he returned to the state to reside in Columbus with his mother and stepfather. After her death he lived a hermitlike existence in a cabin near the town, still fascinating occasional visitors to his retreat with his marvelous powers of conversation.

His contemporaries all agreed that Jones could have achieved a notable professional reputation if he had seriously utilized his obvious talents, but an irresistible compulsion to hoodwink his fellowman led him to seek distinction in a highly unorthodox manner. His death, before age fifty, served to remind the nation of the zany exploits of a remarkable individual who, according to the Raleigh Register, was "as famous in his day as 'Shocco Jones,' as ever was Mr. Randolph as 'John Randolph of Roanoke.'"

References:

Edwin A. Miles, "Joseph Seawell Jones of Shocco—Historian and Humbug," North Carolina Historical Review 34 (October 1957), and ed., "Francis Leech's 'The Mammoth Humbug, or the Adventures of Shocco Jones in Mississippi, in the Summer of 1839,'" Journal of Mississippi History 21 (January 1959).

Additional Resources:

Jones, H.G. "Joseph 'Shocco' Jones, Intriguing Tar Heel." The Times-News [Hendersonville, N.C.]. February 24, 1982. 7. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=JIBPAAAAIBAJ&sjid=ZCQEAAAAIBAJ&pg=5533%2C5059131 (accessed July 31, 2013).

Murray, Alison. “Who Has Not Heard Of Shocco Jones?” North Carolina Miscellany (blog). North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. August 13, 2008 http://blogs.lib.unc.edu/ncm/index.php/2008/08/13/who-has-not-heard-of-shocco-jones/ (accessed July 31, 2013).

Jones, H. G. Scoundrels, Rogues and Heroes of the Old North State. Charleston, S.C.: The History Press. 2007. 245-247. http://books.google.com/books?id=337AcJyhX40C&pg=PA245#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed July 31, 2013).

Cherry, Thomas Kevin B. The Future of Our Past: An Address Delivered Before the North Carolina State Meeting of the Colonial Dames of the XVIIth Century March 21, 2003." North Carolina Libraries. Summer 2003. 62-66. http://www.ncl.ecu.edu/index.php/NCL/article/viewFile/185/214 (accessed July 31, 2013).

Fulkerson, Horace Smith. "Chapter VIII: Shocco Jones in Mississippi." Random Recollections of Early Days in Mississippi. Vicksburg, Miss.: Vicksburg Printing and Publishing Company. 1885. 66-75. http://books.google.com/books?id=aT0VAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA66#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed July 31, 2013).

Image Credits:

"shocco.jpg." Photograph. “Who Has Not Heard Of Shocco Jones?” North Carolina Miscellany (blog). North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. August 13, 2008. http://blogs.lib.unc.edu/ncm/index.php/2008/08/13/who-has-not-heard-of-shocco-jones/

1 January 1988 | Miles, Edwin A.