London, John

23 Oct. 1747–1 March 1816

John London, colonial official, merchant, and banker, was born in Holborn, London, the son of John and Mary Wollaston London and the great-grandson of Sir Robert London who was knighted by Charles II in 1664 for services rendered his father, Charles I. According to a memorandum made by London, he came to North Carolina in the spring of 1764. Sometime between then and November 1764 he was appointed a deputy auditor by Governor Arthur Dobbs. This fact is attested to by a land grant registered in the "office of the Aud. Gen. at Wilmington the 20th of November 1764," which London signed as "D. Aud." On 21 December 1765 he took the oath as "one of the Clerks of the Secretary's office," and in 1768 he was promoted to the position of deputy secretary of the colony. Following the death of Benjamin Heron, secretary of the province, Governor William Tryon, in October 1770, appointed London "Secretary and Clerk of the Crown." He held this office for only two months, resigning in December. London was also clerk of the New Hanover court from 1769 until the fall of 1775, when he was granted a twelve-month leave to settle his personal affairs in England. As he had been a Crown officer, he was not ready at that time to cast his lot with the American Patriots.

John London, colonial official, merchant, and banker, was born in Holborn, London, the son of John and Mary Wollaston London and the great-grandson of Sir Robert London who was knighted by Charles II in 1664 for services rendered his father, Charles I. According to a memorandum made by London, he came to North Carolina in the spring of 1764. Sometime between then and November 1764 he was appointed a deputy auditor by Governor Arthur Dobbs. This fact is attested to by a land grant registered in the "office of the Aud. Gen. at Wilmington the 20th of November 1764," which London signed as "D. Aud." On 21 December 1765 he took the oath as "one of the Clerks of the Secretary's office," and in 1768 he was promoted to the position of deputy secretary of the colony. Following the death of Benjamin Heron, secretary of the province, Governor William Tryon, in October 1770, appointed London "Secretary and Clerk of the Crown." He held this office for only two months, resigning in December. London was also clerk of the New Hanover court from 1769 until the fall of 1775, when he was granted a twelve-month leave to settle his personal affairs in England. As he had been a Crown officer, he was not ready at that time to cast his lot with the American Patriots.

On 20 January 1776 he sailed from Wilmington to England, where he remained for about twenty months. According to a fragmentary diary London kept during his stay, he visited Bristol, Bromsgrove, Stourport, Loughborough, and Glasgow but did not mention the nature of his business in these places. While in Glasgow he was granted on 3 October 1776 a "Burges Ticket," a handsomely illuminated document, which made him a "Burges and gild Brother" of the city. The Burges Ticket entitled him to become a member of the Merchants' House of Glasgow. London evidently made this arrangement so that he could carry on business with the Glasgow merchants at some future time. This proved to be the case, because a few years later he became a member of the mercantile firm of Burgwin, Jewkes and London of Wilmington.

He returned to America on 25 September 1777, landing in New York. Two months later he and Samuel Cornell, a fellow Loyalist from North Carolina, arrived at New Bern in the brig Edwards. They requested permission from Governor Richard Caswell to come ashore to settle their private business under a flag of truce secured from General Henry Clinton for this purpose. Permission to land was granted, but they were instructed not to "proceed further into the Town, than Mr. Cornell's dwelling House." Caswell ordered them to return to New York on the Edwards by 29 December, stipulating that "Mr. London is permitted to take with him his two servants." London did not go to New York but went to Wilmington instead, having received permission from the governor who placed him under parole and limited his movements to the bounds of New Hanover County. London assured Caswell that he would not in any way concern himself "with any measure whatever inimical to the liberty of America."

In September 1778 London applied to the justices of the peace to be allowed to take the oath of allegiance to the state. They turned down his application on the grounds that they doubted its legality since London was in Wilmington on parole under the Confiscation Act. These doubts appear to have been removed, for on 25 January 1779 he was admitted to citizenship. Further evidence of London's return to favor in his community came a year later when Charles Jewkes, commissary to General Alexander Lillington, wrote Governor Caswell requesting £6,000 for provisions to be sent to John London. Jewkes said that London "manages . . . in my absence" and would "do everything that will be wanting for your service." Notwithstanding this show of confidence, London seems to have felt secure in his position, for when the British troops left Wilmington in November 1781, he went with them to Charles Town. He had already been placed under parole not to take up arms against the king when the British occupied Wilmington in January 1781. Remaining in Charles Town until 1783, he took the oath of allegiance and citizenship before the governor of South Carolina. But his citizenship was not recognized in North Carolina, as he soon learned when he returned to Wilmington on 24 July 1783. He was placed under bond to answer any charges made against him under the confiscation acts, as were other citizens who had left the state during the Revolution.

Writing to a friend concerning London's loyalty, Archibald Maclaine remarked that although he and London differed in politics, he preferred having him and others like him "among us . . . than many that shall be nameless." London remained under bond until 1785, when he was formally discharged and was once again in the good graces of his fellow citizens. Summing up his losses of personal property during the Revolution, he estimated them to be £5,795 sterling. In making this estimate he was realistic enough to state that he did not expect to recover his losses, which he never did.

Nevertheless, London was able to purchase property in 1785 on the south side of Market Street in Wilmington where he made his home. In 1796 he was appointed "Treasurer for the Public Buildings" by the New Hanover court and elected one of the Wardens for the Poor. He served for many years as magistrate of police for the town of Wilmington. It was in this capacity that on 1 July 1812 he issued a call for the citizens of Wilmington to meet in the courthouse for the purpose of considering what measures should be adopted "for the security of this Town and its vicinity at this alarming crisis." This is an interesting turn of events, a former Loyalist now providing for the protection of his town against the British.

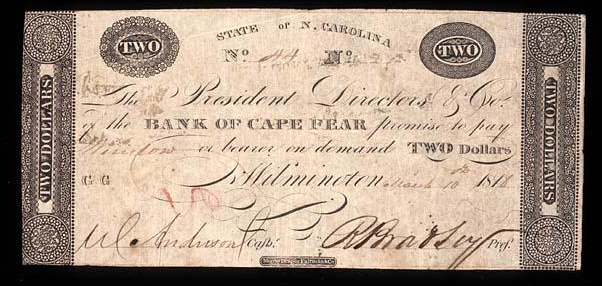

In December 1804 the General Assembly chartered the Bank of Cape Fear, to be located in Wilmington. In the act of incorporation, London was named one of the seven commissioners to solicit the sale of stock in the bank. By August 1805 the required number of shares—one thousand—had been sold. On 19 September the stockholders met at Dick's Hotel in Wilmington to elect eleven directors, one of whom was London. He was reelected a director each year until his death. The Wilmington Gazette for 29 October 1805 carried a notice stating that the Bank of Cape Fear would open for business on 4 November. The notice was signed "Geo. Hooper, President." Hooper held this office until January 1806, when Joshua Grainger Wright was elected president. Wright served until his death on 10 June 1811. London succeeded Wright as president of the bank in 1811 and continued in that office until 1816.

London married first a widow, Peggy Marsden Chivers (1748–86), on 12 July 1785 and by her had one child, John Rutherford (1786–1832). He married second Anne Thorney Mauger (1774–1858) of Charleston, S. C. She was born in St. John's Parish, Isle of Jersey, the daughter of John and Anne Thorney Mauger. In 1783 Anne and her father, then a widower, left Jersey to make their home in Charleston. John London and Anne were married on 12 June 1796 at The Hermitage, a plantation a few miles outside of Wilmington belonging to John Burgwin, an old friend of London. They had ten children, five of whom died in childhood. Those who survived were Henry Adolphus, Mauger, Frances Maria (m. Lallerstedt Mallett), Mary Ashe (m. Thomas Cowan), and Margaret (unmarried).

At the death of his first wife, Peggy Chivers, a rich widow, London inherited the income from her estate for his lifetime. At his death the estate went to their only child, John Rutherford. This inheritance partly explains how London was able to leave his business and take a five-month trip to New York and New England. In a diary London kept of this trip, he stated that he, his wife, and son John left Wilmington on 5 June 1800. Shortly after arriving in New York, he entered John in an academy in Newark, N. J., which was under the direction of the Reverend Uzal Ogden, rector of Trinity Church, Newark. In his diary London made interesting comments on the people he met, the towns visited, the public buildings of the area, particularly churches, and the agriculture of the region. Returning to Wilmington on 6 November, he remarked that the trip had been "one of the most agreeable I ever took" and that it had quite restored his and his wife's health.

No record has been found as to what school, if any, London attended in England before coming to North Carolina. Judging from the style of his letters and the sort of books in his library, he was a man of some intellectual ability. Among his extant collection are eight volumes of Shakespeare's works, Middleton's life of Cicero, the maxims of La Rochefoucauld, the essays of Montaigne, The Iliad and Odyssey, and the poetical and prose works of Pope, Addison, and Goldsmith. All of these volumes were published in London or Edinburgh in the second half of the eighteenth century.

London was a member of the Anglican church. In 1770 he purchased a pew in the newly completed St. James's Church, Wilmington. Following his death, the Wilmington Gazette asserted: "ardent in his attachments, sincere in his friendship, devout in religious exercises, temperate in his habits, and distinguished for method, precision and industry in business, his character presents a fit model for imitation." The officers of the Bank of Cape Fear marched in his funeral procession, and during the day the ships in the harbor flew their colors at half mast. London was buried in Oakdale Cemetery, Wilmington.

References:

Burges Ticket (possession of George E. London, Raleigh).

Walter Clark, ed., State Records of North Carolina, vols. 11–13, 15–16 (1895–99).

Robert O. DeMond, The Loyalists in North Carolina during the Revolution (1940).

Family Bible and manuscripts (possession of Jack London, Uniontown, Ala.).

Don Higginbotham, ed., Papers of James Iredell, vol. 2 (1976).

Donald R. Lennon and Ida Brooks Kellam, eds., Wilmington Town Book, 1743–78 (1973).

Henry Adolphus London Papers (Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill).

John London Diary, 1800 (North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh).

"London Family," in American Families: Genealogical and Heraldic, pp. 279–89 (ca. 1928).

London Family Papers (Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill).

William L. Saunders, ed., Colonial Records of North Carolina, vols. 7–9 (1890).

Henry McG. Wagstaff, ed., Papers of John Steele, vol. 2 (1924).

Alexander McD. Walker, ed., New Hanover County Court Minutes, 1738–1800 (1958).

Wilmington Gazette, 24 Sept., 25 Oct. 1805, 7 Jan. 1806, 6 Jan. 1807, 3 Jan. 1809, 2 Jan. 1810, 13 Jan., 9 Mar. 1816.

Additional Resources:

John London Diary, 1776 (collection no. 02446). The Southern Historical Collection. Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. http://www2.lib.unc.edu/mss/inv/l/London,John.html (accessed January 15, 2014).

London Family Papers, 1764-1933 (bulk 1880s) (collection no. 02442). The Southern Historical Collection. Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. http://www2.lib.unc.edu/mss/inv/l/London_Family.html (accessed January 15, 2014).

Henry Adolphus London Papers, 1770-1885 (collection no. 02011). The Southern Historical Collection. Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. http://www2.lib.unc.edu/mss/inv/l/London,Henry_Adolphus.html (accessed January 15, 2014).

Image Credits:

"Money, Paper, [Bank of Cape Fear] Accession #: H.1978.43.161." 1818. North Carolina Museum of History (accessed January 15, 2014)..

1 January 1991 | London, Lawrence F.