Nichols, William

ca. 1777–12 Dec. 1853

William Nichols, architect and builder, was born in Bath, County Somerset, England, and probably received his early training in England. Arriving in North Carolina in 1800, he was a resident of New Bern by 1805. There he practiced as an architect and builder and may have designed the New Bern Academy building (erected about 1806–10). Nichols moved to Edenton, where he extensively renovated St. Paul's Episcopal Church (1806–9) and had a part in the design and construction of the Palladian mansion at Hayes (ca. 1815–17) and other structures, possibly including Beverly Hall (ca. 1810).

By 1818 Nichols had relocated in Fayetteville. In addition to designing and building public and private structures in that town, he built (ca. 1822) the first local public water supply system, of which he was president and, until 1832, part owner. Most of his Fayetteville buildings undoubtedly were destroyed in the fire that devastated much of the town in 1831. One surviving structure that he probably designed is the Sandford House, built about 1818 as a residence; later it was taken over by the U.S. Bank and then the Woman's Club. As an engineer, Nichols in 1818 gave advice on opening the Cape Fear River to navigation above Fayetteville.

By 1818 Nichols had relocated in Fayetteville. In addition to designing and building public and private structures in that town, he built (ca. 1822) the first local public water supply system, of which he was president and, until 1832, part owner. Most of his Fayetteville buildings undoubtedly were destroyed in the fire that devastated much of the town in 1831. One surviving structure that he probably designed is the Sandford House, built about 1818 as a residence; later it was taken over by the U.S. Bank and then the Woman's Club. As an engineer, Nichols in 1818 gave advice on opening the Cape Fear River to navigation above Fayetteville.

Also in 1818 he was hired to survey the statehouse in Raleigh (built between 1792 and 1796) and advise the General Assembly on needed repairs. After urging extensive improvements in the structure, he was appointed as full-time state architect to plan and execute them. Between 1820 and 1824, Nichols largely rebuilt and greatly improved the building. In the process, it became the second statehouse (Pennsylvania's was the first) to combine the central portico, domed rotunda, and balanced wings housing the two branches of the legislature, which soon became the standard formula for such buildings.

Nichols extended the central pavilions of the east and west fronts to give the ground plan a cross shape, added a third story, fronted the new east and west wings with pseudoporticoes, each consisting of four engaged Ionic columns standing on a rusticated stone basement and carrying a pediment, and stuccoed the brick walls of the structure in imitation of stone. Internally, he formed at the center of the building a rotunda, which he carried up through the roof and capped with a low dome, lighted by a glazed cupola. The rotunda housed Antonio Canova's celebrated statue of George Washington, whose installation Nichols supervised in 1821. The House of Commons was given a semielliptical seating plan (probably derived from the House chamber in the U.S. Capitol) and the Senate a circular seating plan, the members' area being defined in each chamber by a screen of Ionic columns. A classically detailed courtroom was formed on the first floor. While the exterior was essentially Palladian, the interior of the remodeled statehouse must have been a significant early example of neoclassic civic architecture.

In 1825 Nichols designed and, as general contractor, built on Union Square, southeast of the statehouse, a small brick state treasurer's office, which was pulled down about 1840. While in Raleigh, he also directed repairs on the Governor's Palace. He designed (and, in some instances, built) private structures, including the original frame sanctuary of Christ Church (erected in 1829) and the two-story southern section of the Mordecai House (1826) with its two-tiered, pedimented portico, a Palladian design feature that he also used on the Sandford House in Fayetteville.

The University of North Carolina engaged Nichols to design and erect what is now the southern two-thirds of Old West Dormitory (1822–23) and concurrently to add a third story to its pendant, Old East. Thus he established the symmetrical, north-oriented campus plan that prevailed until the end of the century. He also designed and began constructing Gerrard Hall (erected between 1822 and 1837) as a chapel and an assembly hall, which featured a colossal four-columned, pedimented Ionic portico on its southern flank. All three buildings, although modified, survive in form and function. Nichols made alterations to South Building and other university structures during the same period. His work on the campus ended in 1827.

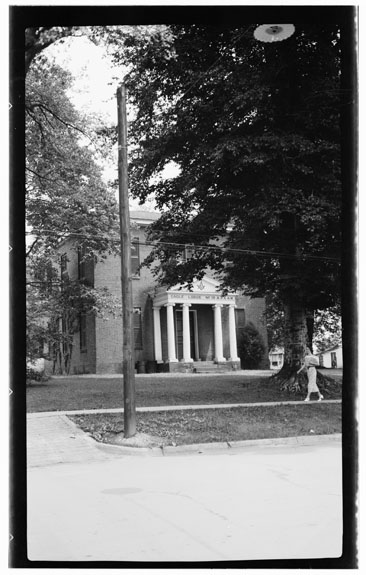

Other North Carolina buildings designed by Nichols include the surviving Eagle Masonic Lodge (built between 1823 and 1825) in Hillsborough and, according to Governor David L. Swain, courthouses for Davidson and Guilford counties. Swain said that Nichols, the first North Carolina architect-builder to operate statewide, "was a skillful and experienced artist, and made the public greatly his debtor for a decided impulse given to architectural improvements throughout the State, in private as well as in public edifices."

Other North Carolina buildings designed by Nichols include the surviving Eagle Masonic Lodge (built between 1823 and 1825) in Hillsborough and, according to Governor David L. Swain, courthouses for Davidson and Guilford counties. Swain said that Nichols, the first North Carolina architect-builder to operate statewide, "was a skillful and experienced artist, and made the public greatly his debtor for a decided impulse given to architectural improvements throughout the State, in private as well as in public edifices."

Probably in search of a more profitable area of operation, Nichols moved to Alabama in 1827. There he designed at Tuscaloosa a state capitol (built between 1827 and 1829) that was very similar in plan to his remodeled North Carolina statehouse but grander in scale and finer in finish than the older structure. Abandoned as the capitol in 1846, this building housed a school until it burned in 1923. For the University of Alabama, also at Tuscaloosa, Nichols in 1828 designed the original buildings, ordering them in a quadrangle with a rotunda at its head after the manner of Thomas Jefferson's plan for the University of Virginia. Most of Nichols's University of Alabama buildings were burned by Federal soldiers in 1865, the only survivors being the Gorgas House (built between 1828 and 1831), the Observatory, and the monumental President's Mansion (completed in 1841).

The North Carolina statehouse burned in 1831. The legislative act providing for construction of the capitol (as the successor building has always been known) directed that it be an enlarged version of the statehouse. Nichols and his son, William, Jr., were engaged by the commissioners for rebuilding to provide the initial plan, and the younger Nichols arrived in Raleigh in the spring of 1833 to work with the commissioners. In July 1833 the Nichols plan was approved by the commissioners, the two architects were paid, and their connection with the capitol ended. No drawing illustrating the Nichols design has been found, but from contemporary descriptions, it clearly was a further refinement on a larger scale of the cruciform plan that William Nichols had devised for North Carolina in 1820–24 and improved upon for Alabama in 1827–29. The Nicholses determined the ground plan, general dimensions, and massing of the capitol and the disposition of the principal functions within it. Their successor architects, Town and Davis of New York (August 1833–35) and David Paton (1835–40), modified and greatly refined but could not fundamentally alter the basic design.

William Nichols's fourth state capitol design was his 1835 plan for altering and enlarging the former Charity Hospital on Canal Street in New Orleans to serve as the Louisiana state capitol. His fifth and final state capitol was that at Jackson, Miss., which he designed and built between 1836 and 1839. Another grand variation on his basic statehouse scheme, it drew praise from Talbot Hamlin as "expressive of much that was best in the creative thinking and the sensitive aesthetic feeling of its time." It is the only one of Nichols's five statehouses that stands largely as he designed it (though much of the interior is a recent re-creation, not his original work). His other structures in Jackson included the state penitentiary (completed in 1840) and the handsome Greek Revival Governor's Mansion (completed in 1842), recently restored and still in use. For the University of Mississippi at Oxford, he designed the Lyceum (completed in 1848) and other buildings.

William Nichols became a naturalized citizen in 1813. His first wife was Mary Rew, whom he married in Craven County in 1805; his second wife was Sarah Simons, whom he married in Chowan County in 1815. Nichols had at least two children, William, Jr., and Samuel, both of whom married North Carolina residents. Nichols died and was buried in Lexington, Miss. In his obituary, the Mississippian said of him: "He has left enduring monuments of his genius, and will long be remembered for many excellent qualities as a man and a citizen."

References:

Gertrude S. Carraway, Years of Light (1944). https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/16929 (accessed October 3, 2014).

Cecil D. Elliot, "The North Carolina State Capitol," Southern Architect 5, no. 6 (June 1958).

Talbot F. Hamlin, Greek Revival Architecture in America (1944).

Ralph Hammond, Ante-Bellum Mansions in Alabama (1951).

Henry-Russell Hitchcock and William Seale, Temples of Democracy: The State Capitols of the USA (1976).

Legislative Papers, 1818–25 (North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh).

Additional Resources:

"Nichols, William (1780-1853)." North Carolina Architects & Builders, NCSU Libraries. http://ncarchitects.lib.ncsu.edu/people/P000026 (accessed October 3, 2014).

"Moredecai House." Raleigh: A Capital City. National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/nr//travel/raleigh/mor.htm (accessed October 3, 2014).

Bishir, Catherine W. 1990. North Carolina architecture. Chapel Hill: Published for the Historic Preservation of North Carolina by the University of North Carolina Press.

Image Credits:

Biggs, Archie A. "VIEW OF FRONT FROM STREET. - Eagle Lodge, 142 West King Street, Hillsborough, Orange County, NC". Photograph. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/nc0063.photos.102579p/ (accessed October 3, 2014).

Helget, Kellie Jo. "Sandford-House-Fayetteville-NC-2." Photograph. August 2008. Wikimedia Commons. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sandford-House-Fayetteville-NC-2.JPG (accessed October 3, 2014).

1 January 1991 | Sanders, John L.