Owen, Benjamin Wade

4 June 1904–7 Oct. 1983

Benjamin Wade Owen, traditional potter, was born and raised near the Westmoore community in northwestern Moore County, the son of Rufus and Martha McNeill Owen. As a member of a large clan of potters, Owen learned to make pottery alongside his brothers Charlie (b. 1901) and Joe (1910–86) at the family shop. Between the seasonal demands of farming, their father provided informal but practical training in all phases of the craft. As Owen recalled: "I'd help him knead up his clay—weigh it out and knead it up—and help him lift his jars off. And when he'd be doing something else—putting on handles on something else—I'd be trying to make me some little jugs and pitchers to sell." By the time he was sixteen, he was a proficient potter and did some work as a journeyman at other shops. Like the other potters in this region, he produced lead-glazed earthenware pie dishes and flowerpots, as well as salt-glazed stoneware jars, jugs, pitchers, churns, and milk crocks, all familiar, utilitarian forms used in local homes and on farms.

Benjamin Wade Owen, traditional potter, was born and raised near the Westmoore community in northwestern Moore County, the son of Rufus and Martha McNeill Owen. As a member of a large clan of potters, Owen learned to make pottery alongside his brothers Charlie (b. 1901) and Joe (1910–86) at the family shop. Between the seasonal demands of farming, their father provided informal but practical training in all phases of the craft. As Owen recalled: "I'd help him knead up his clay—weigh it out and knead it up—and help him lift his jars off. And when he'd be doing something else—putting on handles on something else—I'd be trying to make me some little jugs and pitchers to sell." By the time he was sixteen, he was a proficient potter and did some work as a journeyman at other shops. Like the other potters in this region, he produced lead-glazed earthenware pie dishes and flowerpots, as well as salt-glazed stoneware jars, jugs, pitchers, churns, and milk crocks, all familiar, utilitarian forms used in local homes and on farms.

Owen's life took a dramatic turn in 1923, when Jacques Busbee offered him a job at the newly established Jugtown Pottery. Together with his wife Juliana, Busbee sought to revitalize the native pottery industry by introducing new forms and glazes and developing new markets outside of the region. Since he was not a potter himself, Busbee had to rely on the skilled hands of local men. He soon found that the members of Rufus Owen's generation wanted no part in such innovations and had no desire to make "toys," as they scornfully referred to the smaller and more decorative wares. And so Busbee hired the younger potters, first Charlie Teague (1901–38) and then Ben Owen: "He came to my house and wanted to know if I'd come down and try. He wanted some young potters that he could show and tell. The older potters, he said, was harder to get it in their heads what he wanted."

The fusion of Jacques Busbee's vision with Ben Owen's skills eventually earned an international reputation for the Jugtown Pottery. Busbee patiently educated the young man in the ceramic traditions of the Orient, most notably works from the Han, T'ang, and Sung dynasties of China. He took Owen to museums in New York and Washington, D.C., and provided sketches, photographs, pictures, and even a tea bowl to study and imitate. Owen found that "it didn't take me long to get on to it," but he soon learned that he had to finish these pieces much more carefully than the old utilitarian wares. "It had to be just right or he wouldn't have it. . . . He wanted it to be just like the picture or the model." Busbee did not neglect the old forms—Owen continued to turn jugs, jars, pitchers, pie dishes, and ring jugs—but now the Jugtown repertory included equal numbers of Han vases, Sung bowls, Korean bottles, and Persian jars. Likewise, Owen learned about new glazes—white, mirror black, Chinese blue—to go with the old lead, salt, and frogskin types. In all, the collaboration of the two men produced a classic pottery unlike that made anywhere else, a blend of old and new founded on the principles of restraint and simplicity that were inherent in both the native folk and Oriental traditions.

Jacques Busbee died in 1947, but Ben Owen remained at Jugtown until 1959, when the business was sold to John Maré. After a disagreement with the new owner, Owen left and founded the Old Plank Road Pottery, where he continued to produce the same forms and glazes until his retirement in 1972. During this final phase of his career, he stamped his pottery with his own name: Ben Owen/Master Potter. Fittingly, Owen's work has been widely exhibited in North Carolina, the United States, and abroad. Permanent collections may be found in such institutions as the Mint Museum, Charlotte; the North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh; the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and the Louvre, Paris.

Jacques Busbee died in 1947, but Ben Owen remained at Jugtown until 1959, when the business was sold to John Maré. After a disagreement with the new owner, Owen left and founded the Old Plank Road Pottery, where he continued to produce the same forms and glazes until his retirement in 1972. During this final phase of his career, he stamped his pottery with his own name: Ben Owen/Master Potter. Fittingly, Owen's work has been widely exhibited in North Carolina, the United States, and abroad. Permanent collections may be found in such institutions as the Mint Museum, Charlotte; the North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh; the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and the Louvre, Paris.

Although severely impacted by arthritis late in life, Owen had the pleasure of watching his son and grandson revive his work. From his marriage to Lucille Harris on 27 Mar. 1937, there were two children: Benjamin Wade, Jr., and Jane. Son Wade worked at the Old Plank Road Pottery but then moved on to other occupations such as farming and teaching. However, in late 1982, he and his son, Benjamin Wade III, reopened the shop as the Ben Owen Pottery and began producing a full line of old North Carolina forms and Oriental translations, most of them based closely on the earlier work of the master. In his last years, Ben Owen was able to teach and encourage his grandson, thus extending the tradition he had learned as a boy. He died of a heart attack after a bout with pneumonia and was buried at the nearby Union Grove Baptist Church, the final resting place of many generations of North Carolina potters.

References:

Ben Owen Pottery (1974) (exhibition catalogue, North Carolina Museum of History).

Jean Crawford, Jugtown Pottery: History and Design (1964).

Jugtown Pottery: The Busbee Vision (1984) (exhibition catalogue, North Carolina Museum of Art).

Benjamin Wade Owen, "Reflections of a Potter," The State of the Arts (April 1969), newsletter of the North Carolina Arts Council.

Charles G. Zug III, Turners and Burners: The Folk Potters of North Carolina (1986).

Additional Resources:

"Benjamin Wade Owen." North Carolina Pottery Collection. The Mint Museum. 2012. http://ncpottery.mintmuseum.org/nc-pottery/nc-potters/detail/501156/Benjamin-Wade-Owen (accessed October 10, 2013).

"Jugtown Pottery Era." Ben Owen Pottery. http://www.benowenpottery.com/about-us/history/jugtown-pottery-era.html (accessed October 10, 2013).

Image Credits:

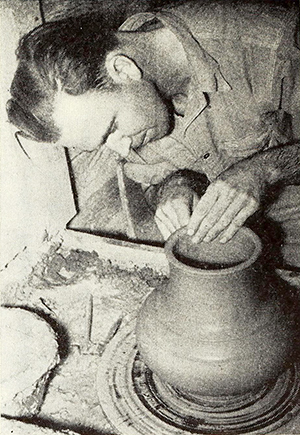

State News Bureau. "Forming a pot on the 'kickwheel' from soft clay is B.W. Owen, chief potter at the Jugtown Pottery." The E.S.C. Quarterly 5, nos. 2-3. (Spring-Summer 1947) 60. https://archive.org/stream/escquarterly00nort#page/n65/mode/2up (accessed October 10, 2013).

"Ring Jug, Accession #: H.2006.23.23." 1960-1972. North Carolina Museum of History.

1 January 1991 | Zug, Charles G., III