The Art of John White

By Suzanne Mewborn

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian, Fall 2007.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

If you travel to a new place, you probably will want to pack your suitcase with things like clothing, shoes, and shampoo. One item that you definitely want to include is your camera! Taking pictures of places and people reminds you of where you have been and whom you have met. Photographs document your trip and allow you to share your experiences with friends back home. Those who were part of the 1585 English expedition to Roanoke Island had the same idea in mind.

Seventy-five drawings that artist John White made on that trip have survived. White’s drawings—each approximately ten inches by five inches—give us a glimpse of the people living in present-day North Carolina more than four hundred years ago. These sketches are our only visual record of the American Indians before European contact, and we are lucky to be able to view them today. In 1865 the drawings were in a warehouse that caught fire. They did not burn but did get soaked by water. For three weeks, they lay flattened by other books piled on top of them. When someone rescued White’s drawings—which eventually ended up in the care of the British Museum—they found sheets of paper between them. “Offsets” of the original drawings had stamped onto these loose sheets of paper. The drawings were no doubt extremely bright and colorful before this blotting happened. White used watercolors to bring his pictures to life. Sometimes he even used gold and silver highlights, particularly when drawing fish. The gold and silver remain on the offsets, mirror images of the originals now bound into a volume. The original drawings have been preserved and individually framed.

While Thomas Harriot wrote detailed descriptions of the 1585 landscape so foreign to the English explorers, White sketched their observations. Harriot was a well-known author, mathematician, and astronomer. Sir Walter Raleigh paid him to teach Raleigh and his employees about navigation, in preparation for the first English voyages to the New World. References to Harriot’s life and talents are fairly easy to find in historical records, but White largely remains a mystery. We do not know when or where he was born or died. Because John White is a relatively common name, it is challenging to find information about the John White who traveled to Roanoke. Also, few documents from that time survive. Despite our lack of knowledge about the man, we can see his talents for what the English called the fine gentlemanly skill of limning (another word for drawing and painting) in his work.

When studying these historical images, we must keep in mind that we are looking at early American Indians through an Englishman’s eyes and mind. An interpretation is an explanation of the meaning behind a person’s artistic or creative work. What was White’s interpretation of the Indians? What did he want the audience of his time to see and learn from his drawings? And why are his drawings important today?

Europeans at the time viewed White’s drawings as lifelike renderings of a very mysterious place. In addition to detailed portraits of the people living in what is now North Carolina, drawings include various plants and animals unfamiliar to Europeans. White created them with black lead or graphite during the expedition, and then probably filled them in with more detail and watercolor on board ship or the long voyage back to England. Modern conservators—people who care for, restore, and repair historical artifacts—at the British Museum have determined that the watercolor was applied after the paper was folded. White had folded his paper so that it would be easier to take along and use for sketching in the field.

The reasons behind White’s artwork relate to the wave of voyages to the New World, when what we consider the modern age of history was beginning. The Portuguese, Spanish, French, and English wanted to find water routes to Asia. Water routes would make it easier to carry luxury goods back to sell in Europe. When Columbus landed in North America in 1492, he thought he was near India. In 1497 John Cabot claimed North America for the English monarch, and in 1524 and 1534, the French claimed different areas of the continent. But when Spain soon established colonies in the Caribbean and began exploring present-day Florida, the English really became fearful of Spanish power. The Spanish wanted complete control of North America and its natural resources.

Advisers began telling England’s Queen Elizabeth I about some of the advantages of colonizing North America: blocking the Spanish, finding new trade routes, and having a place to send troubled soldiers and prisoners. One man arguing for colonization was Raleigh. Once the queen approved of his plan to send a group to the New World, Raleigh was sure to include the “skillful painter” White on the list of men who would go. White and Harriot gathered information similar to modern travel brochures.

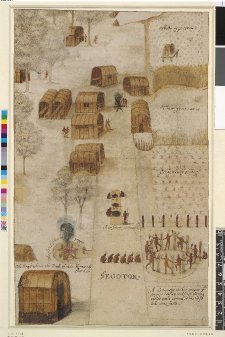

White’s images illustrated ways that the American Indians might be useful to English colonization. Europeans could see productive and welcoming inhabitants with ample food and land. Their villages were orderly, and they demonstrated their intelligence by using nature to survive and flourish. In White’s drawing The Indian village of Secoton, houses appear along a central lane. There are trees on one side. On the other side, Indians have cleared land for planting. White shows three plantings of corn in different stages of growth: “corne newly sprong,” “greene corne,” and “rype corne.” Three cornfields emphasize the productivity of land and food. White’s images stress a natural abundance that would enable the English to survive and grow.

White’s images illustrated ways that the American Indians might be useful to English colonization. Europeans could see productive and welcoming inhabitants with ample food and land. Their villages were orderly, and they demonstrated their intelligence by using nature to survive and flourish. In White’s drawing The Indian village of Secoton, houses appear along a central lane. There are trees on one side. On the other side, Indians have cleared land for planting. White shows three plantings of corn in different stages of growth: “corne newly sprong,” “greene corne,” and “rype corne.” Three cornfields emphasize the productivity of land and food. White’s images stress a natural abundance that would enable the English to survive and grow.

Another drawing that emphasizes the abundance of food in the New World is Indians Fishing. White shows American Indians in a canoe with fire between them. A fire was used to attract fish, particularly at night. In addition to other people in the background fishing with spears, White includes detailed drawings of various fish that the Indians might catch. Shellfish and a fish trap appear on the left side of the drawing, and birds are flying in the sky. White fills the page with signs of plentiful food. The Native people can feed themselves; maybe the English hoped that they could feed the colonists, too.

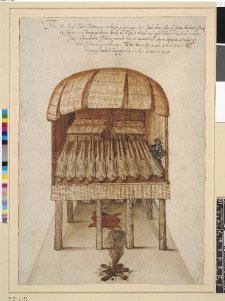

White also includes observations that might challenge English colonization and English relationships with the American Indians, such as religious differences. For example, White draws An Ossuary Temple, a building that houses bodies of deceased Indian chiefs that have been mummified, a ritual that Christians do not perform. A squatting idol overlooks the preserved bodies, suggesting that the Indians were a pagan society that worshipped many different gods instead of Christians’ single God. The lack of clothing worn by the Indians in the drawings shows the warm climate at Roanoke and differences from English customs. Two detailed drawings of villages indicate a relatively large Native population needing food and land of its own. Palisades surround one village, showing the American Indians’ capability to make war and to protect themselves. These drawings served as a reminder to English settlers and investors of possible disagreements to overcome.

White also includes observations that might challenge English colonization and English relationships with the American Indians, such as religious differences. For example, White draws An Ossuary Temple, a building that houses bodies of deceased Indian chiefs that have been mummified, a ritual that Christians do not perform. A squatting idol overlooks the preserved bodies, suggesting that the Indians were a pagan society that worshipped many different gods instead of Christians’ single God. The lack of clothing worn by the Indians in the drawings shows the warm climate at Roanoke and differences from English customs. Two detailed drawings of villages indicate a relatively large Native population needing food and land of its own. Palisades surround one village, showing the American Indians’ capability to make war and to protect themselves. These drawings served as a reminder to English settlers and investors of possible disagreements to overcome.

Despite the differences in clothing, language, religion, and social organization, White shows some similarities between the English and Indians. His portraits of elders and chiefs told interested colonists about more than just each individual subject. Overall, the people in the portraits are smiling, laughing, or talking. They wear ornaments such as necklaces, headbands, earrings, and feathers. The Indians’ ornaments—such as bracelets and necklaces of copper and pearls —emphasized something in common with the English. Clothes and jewelry could identify American Indian leaders, just as they did English rulers and people of wealth. Think about portraits of Queen Elizabeth. She is covered with pearls, jewels, and rich fabrics. White’s drawings of Indians include wood, fur,  leather, shells, clay, stone, beads, and copper. Some of these materials were used to make weapons. White was sure to include them in his drawings as resources available in the New World. These resources were important for trading with American Indians or for making money by selling them back in Europe. White’s drawing of An Indian Man and Woman Eating might suggest that both groups had social lives and organized gatherings, as also seen in A Fire Ceremony. Indians Fishing illustrates that, like the English, American Indians worked in teams.

leather, shells, clay, stone, beads, and copper. Some of these materials were used to make weapons. White was sure to include them in his drawings as resources available in the New World. These resources were important for trading with American Indians or for making money by selling them back in Europe. White’s drawing of An Indian Man and Woman Eating might suggest that both groups had social lives and organized gatherings, as also seen in A Fire Ceremony. Indians Fishing illustrates that, like the English, American Indians worked in teams.

White includes a variety of snapshots in his images: portraits, landscapes, detailed animal studies, and maps. People such as Theodor de Bry—an engraver working in Germany—later published versions of White’s drawings in several languages. De Bry made changes, such as making the Indians’ facial features, coloring, and poses look more like typical European portraits of the time. In the same way that a story changes with each person

who tells it, the drawings changed, too.

At the time of this article’s publication, Suzanne Mewborn served as the program coordinator for the Tar Heel Junior Historian Association at the North Carolina Museum of History.

References and additional resources:

Resources in libraries via WorldCat

Image Credits:

© The Trustees of the British Museum

1 January 2007 | Mewborn, Suzanne