Civil War Desertion

Civil War desertion by North Carolina troops remains a controversial topic. Owing to the fragmentary nature of surviving records, researchers have arrived at different conclusions as to how many North Carolina soldiers actually deserted the Confederate army. Soon after the conflict, the U.S. Army's provost marshal general officially estimated that 23,000 North Carolina troops deserted between 1861 and 1865, nearly one-quarter of the total for the entire Confederacy and significantly more than for any other state. Historians have challenged this estimate, one suggesting that a more accurate figure, based on his quantitative analysis of compiled service records, would be about 14,000 desertions.

Civil War desertion by North Carolina troops remains a controversial topic. Owing to the fragmentary nature of surviving records, researchers have arrived at different conclusions as to how many North Carolina soldiers actually deserted the Confederate army. Soon after the conflict, the U.S. Army's provost marshal general officially estimated that 23,000 North Carolina troops deserted between 1861 and 1865, nearly one-quarter of the total for the entire Confederacy and significantly more than for any other state. Historians have challenged this estimate, one suggesting that a more accurate figure, based on his quantitative analysis of compiled service records, would be about 14,000 desertions.

Although debate continues over exact numbers, undoubtedly the absence of North Carolina troops without leave represented a serious problem for the Confederate army. Gen. Robert E. Lee complained about North Carolina's desertion rate. Many North Carolinians bitterly resented these charges, seeing them as yet another example of the Confederate government's alleged discrimination against their state. Virginia newspapers routinely impugned the effectiveness of North Carolina troops.

Nevertheless, the state did have an unusually high rate of desertion. Several factors contributed to this exodus. Many men left the army after they became aware of the hardships and danger encountered by their families back home. As the ravages of war worsened, wives increasingly wrote letters encouraging their soldier-husbands to desert. Desertion generally increased in a unit when the region from which it had been recruited fell into enemy hands, as did several coastal counties. Desertions also occurred in areas where civilians experienced extreme suffering and law and order broke down, as in several western counties.

Nevertheless, the state did have an unusually high rate of desertion. Several factors contributed to this exodus. Many men left the army after they became aware of the hardships and danger encountered by their families back home. As the ravages of war worsened, wives increasingly wrote letters encouraging their soldier-husbands to desert. Desertion generally increased in a unit when the region from which it had been recruited fell into enemy hands, as did several coastal counties. Desertions also occurred in areas where civilians experienced extreme suffering and law and order broke down, as in several western counties.

The state's 1864 peace movement, led by Raleigh Standard editor William W. Holden, may also have contributed to poor morale and desertion among North Carolina soldiers, although Holden publicly condemned this practice. The rulings of North Carolina Supreme Court chief justice Richmond Pearson against the legality of conscription also led many deserters to believe that if they reached their home state, its legal authorities would shield them from punishment. Although some deserters were conscripts who saw little or no active service and some were members of the Unionist secret society called the Heroes of America, many more were relatively devoted Confederates. More than half the state's deserters had served in the army for more than 18 months and almost 70 percent for more than a year. These men apparently felt a greater loyalty to their families, who desperately needed their assistance, or perhaps they recognized the futility of the Confederate cause, particularly in the last, hopeless days of the war.

Educator Resources:

Futch Civil War Letters Lesson Plan, State Archives of North Carolina

References:

Richard Bardolph, "Inconstant Rebels: Desertion of North Carolina Troops in the Civil War," NCHR 41 (April 1964).

James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (1988).

Richard Reid, "A Test Case of the 'Crying Evil': Desertion among North Carolina Troops during the Civil War," NCHR 58 (July 1981).

Additional Resources:

Richmond Pearson, NC Highway Historical Marker M-12: https://www.ncdcr.gov/about/history/division-historical-resources/nc-highway-historical-marker-program/Markers.aspx?ct=ddl&sp=search&k=Markers&sv=M-12%20-%20RICHMOND%20PEARSON%201805-1878 (accessed October 5, 2012).

Desertion in the Tarheel State, NCSU: http://history.ncsu.edu/projects/cwnc/exhibits/show/ncdesertion/response-to-desertion

North Carolina and the Civil War, North Carolina Museum of History: http://www.ncmuseumofhistory.org/exhibits/civilwar/resources_section7d.html

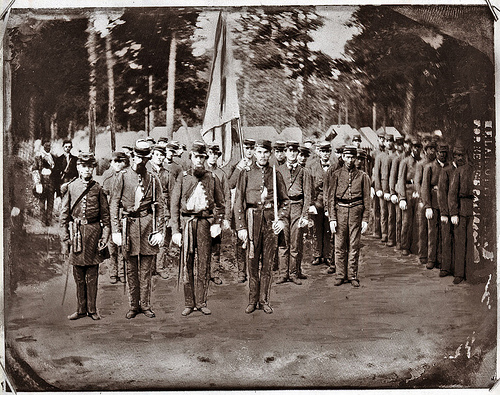

Image Credit:

N_61_10_4 Confederate Grays, Co E 20the Regiment NCT, Duplin Co From the General Negative Collection, North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh, NC. Available from https://www.flickr.com/photos/north-carolina-state-archives/4290086635/ (accessed October 5, 2012).

1 January 2006 | Smith, Michael Thomas