Disfranchisement

See also: Grandfather Clause; Poll Tax.

Disfranchisement refers to a constitutional amendment drafted by the 1899 North Carolina General Assembly and approved in the general election in 1900 severely limiting African Americans' right to vote. The intent of disfranchisement was to repudiate the principle of universal male suffrage, especially black suffrage, and to replace it with laws that ensured that only literate white males could vote.

Federal and state constitutional measures adopted during Reconstruction had prohibited the denial of voting rights on the basis of race. The Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1870, banned any infringement on a citizen's right to vote "on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude," thus giving the federal government domain over voting qualifications. Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, however, access to the ballot in North Carolina was a matter of contention. The Democratic-controlled legislature passed laws that enabled it to control the registration and vote-counting processes. Under this system, bribery, intimidation, and fraud were common. Yet in 1894 the Democratic election machinery was overthrown by the new Populist-Republican "Fusion" government. Fusionist laws passed by the General Assembly in 1895 and 1897 made it easier for illiterates and blacks to vote and reduced the likelihood of fraud.

Federal and state constitutional measures adopted during Reconstruction had prohibited the denial of voting rights on the basis of race. The Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1870, banned any infringement on a citizen's right to vote "on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude," thus giving the federal government domain over voting qualifications. Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, however, access to the ballot in North Carolina was a matter of contention. The Democratic-controlled legislature passed laws that enabled it to control the registration and vote-counting processes. Under this system, bribery, intimidation, and fraud were common. Yet in 1894 the Democratic election machinery was overthrown by the new Populist-Republican "Fusion" government. Fusionist laws passed by the General Assembly in 1895 and 1897 made it easier for illiterates and blacks to vote and reduced the likelihood of fraud.

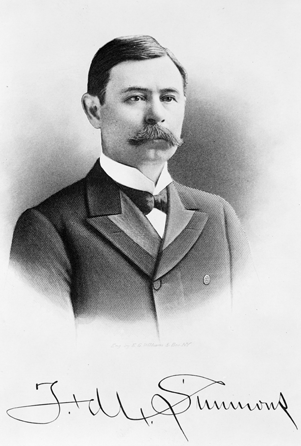

By the election campaign of 1898, Democratic leaders, particularly Furnifold M. Simmons of New Bern, had decided that a dramatic restriction of the franchise would eliminate the complexities of voting in the post-Civil War era and ensure Democratic rule. Recognizing the sensitivity of poorer whites to curbs on voting, Democratic candidates naturally denied they would enact such legislation if elected. Using violence and intimidation against Populist and Republican opponents, the Democratic Party regained control of the General Assembly, which in 1899 approved a constitutional amendment restricting the right to vote. The lawmakers then scheduled a special election to be held on 2 Aug. 1900 for public consideration of the amendment.

The disfranchisement amendment was worded in such a way that it circumvented the federal prohibition of overt racial discrimination in voting procedures. Neutral on its face, it merely required prospective voters to pay a poll tax and to pass a literacy test. However, the poll tax was costly to the poor and, of course, applied only to those intending to vote. In addition, in 1900 almost 30 percent of all voting-age males were illiterate, a disproportionate percentage of whom were poor African Americans. Further, the proposed amendment would operate in conjunction with new registration laws passed in 1899 that gave Democrats control of deciding which persons had properly registered. Finally, to appeal to some whites, the amendment included a grandfather clause that allowed an illiterate to qualify if he or a lineal ancestor had been a registered voter before 1867-that is, prior to Congressional Reconstruction-provided he registered by 1908. The grandfather clause indicated that the short-term purpose of disfranchisement was to eliminate black voters.

The debate over the amendment reached its climax in the summer of 1900. Generally, Republicans and Populists opposed the measure, while Democrats, including gubernatorial candidate Charles B. Aycock, supported it. The greatest concern of Republicans and Populists was the potential disfranchisement of poor whites, not African Americans, yet many supported the amendment. In an election characterized by registration abuses by Democratic officials, more violence and intimidation on the part of Democratic ruffians and groups such as the Red Shirts, and elaborate demonstrations of white supremacists, the disfranchisement amendment passed easily.

The effect of the disfranchisement amendment on North Carolina elections was revolutionary. Between 1900 and 1902, white turnout plummeted and black turnout was almost nonexistent. Not until the 1960s, with the passage of strong federal voting rights legislation, did its continuing impact begin to dissipate.

References:

Jerry W. Cotten, "Negro Disfranchisement in North Carolina: The Politics of Race in a Southern State" (M.A. thesis, UNC-Greensboro, 1973).

Jeffrey J. Crow and Robert F. Durden, Maverick Republican in the Old North State: A Political Biography of Daniel L. Russell (1977).

Helen G. Edmonds, The Negro and Fusion Politics in North Carolina, 1894-1901 (1951).

James L. Hunt, "Marion Butler and the Populist Ideal, 1863-1938" (Ph.D. diss., University of Wisconsin, 1990).

J. Morgan Kousser, The Shaping of Southern Politics: Suffrage Restriction and the Establishment of the One-Party South, 1880-1910 (1974).

Additional Resources:

"The Suffrage Amendment." ANCHOR. https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/suffrage-amendment

Malburne-Wade, Meredith. "Summary of The Proposed Suffrage Amendment. The Platform and Resolutions of the People's Party." from Documenting the American South at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 2004.

"The North Carolina Election of 1898." North Carolina Collection of The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. http://www.lib.unc.edu/ncc/1898/1898.html

Michael Perman, Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888-1908. Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2001.

Image Credits:

Engraving of Furnifold M. Simmons with facsimile autograph, by E.G. Williams and Bro., New York. Image from the State Archives of North Carolina. Call number N_53_15_644.

1 January 2006 | Hunt, James L.