Great Depression

See also: Great Depression and the New Deal; Blue Ridge Parkway; Federal Writers' Project; Fontana Dam; State Planning Board; Agriculture in NC during the Great Depression; Public schools in NC during the Great Depression.

The Great Depression in North Carolina caused immeasurable hardship for a large percentage of citizens and, by way of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal programs, brought the federal government into the lives of average North Carolinians more than ever before, fundamentally changing the relationship between individuals and government. The Depression was quantitatively the single largest economic downturn the United States and the world had ever experienced. It began in August 1929 and did not effectively end until December 1941 with U.S. involvement in World War II. In 1933, when Roosevelt took office, the nation was plagued by relentless economic depression. Between August 1929 and March 1933 industrial production had fallen by more than 50 percent, deeply damaging the world's economy. The money supply had dropped by more than 30 percent, as had the general level of prices, and the financial system had been decimated by a series of banking crises and panics.

The Great Depression in North Carolina caused immeasurable hardship for a large percentage of citizens and, by way of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal programs, brought the federal government into the lives of average North Carolinians more than ever before, fundamentally changing the relationship between individuals and government. The Depression was quantitatively the single largest economic downturn the United States and the world had ever experienced. It began in August 1929 and did not effectively end until December 1941 with U.S. involvement in World War II. In 1933, when Roosevelt took office, the nation was plagued by relentless economic depression. Between August 1929 and March 1933 industrial production had fallen by more than 50 percent, deeply damaging the world's economy. The money supply had dropped by more than 30 percent, as had the general level of prices, and the financial system had been decimated by a series of banking crises and panics.

In North Carolina, then primarily an agricultural state, the deflation of crop prices was devastating. In 1933 gross farm income was only 46 percent of its 1929 level. The banking community that was so closely linked to the farming community consequently grew weaker and more desperate, and the absence of credit for farmers compounded an already miserable situation. Mass unemployment had become increasingly widespread across the state and nation. By 1933 in North Carolina, 27 out of every 100 persons were on relief; mountain and coastal regions were hardest hit. As one editor of an eastern North Carolina newspaper put it, "a trail of poverty" ran through Northampton, Martin, Bertie, Gates, and Halifax Counties.

North Carolina industries saw the decline in manufacturing value added by more than 50 percent-from $1.3 billion in 1930 to $878 million in 1933. From 1929 to 1933 North Carolina cotton and textile industry wages declined 25 percent. Falling wages and mass unemployment led to substantial labor unrest across the state.

New Deal Agencies in North Carolina

Jump to: Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) | Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) | Public Works Administration (PWA) | Works Progress Administration (WPA) | Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) | National Youth Administration (NYA) | National Recovery Administration (NRA) | Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) | Social Security Act (SSA)

On becoming president, Roosevelt immediately instituted many reforms that had an instant positive impact in North Carolina and throughout the nation. These expedients included removing the gold standard for U.S. currency, instituting a bank holiday for a three-day period in 1933, and establishing federal deposit insurance and a series of measures to provide financial rehabilitation for the banking community, debtors, and individuals seeking credit. Perhaps most important to North Carolina and other states, the Roosevelt administration established New Deal programs that greatly aided the economy, made needed improvements to North Carolina's transportation and other infrastructures, built numerous public-use and cultural facilities, and created employment opportunities for thousands of citizens.

Few states were willing to wholeheartedly accept the liberalism of the New Deal's revolutionary programs, and North Carolina was no exception. The state's relative poverty, and the allocation of federal welfare and construction funds on a matching basis, made full participation in the programs difficult. Governors John C. B. Ehringhaus and Clyde R. Hoey and the legislature, dominated by farmers and conservative businessmen, were determined to both resist Roosevelt's advanced social agenda and maintain a balanced state budget. Nevertheless, several New Deal initiatives had wide influence in North Carolina.

Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA). The the most important New Deal program for North Carolina, the AAA initiated farm production control that proved to be a boon to tobacco, though less to cotton. During the early years of the Depression, tobacco prices plummeted from around 20.0 cents per pound during the end of the 1920s to 8.4 cents in 1931. Cotton prices fell from 22 cents a pound in 1925 to 6 cents in 1931. To improve crop prices, the AAA offered rental and benefit payments to farmers who reduced crop production. County agents of the Agricultural Extension Service worked with local committees of farmers to administer the program.

Agricultural officials focused first on cotton. Because crops for the 1933 season had already been planted, the AAA decided that farmers nationally had to plow up 10 million acres of planted cotton. North Carolina's 150,000 cotton farmers mobilized by signing individual contracts to destroy part of their crop in return for government payments. The plan brought immediate positive results. Cotton prices rose from 7.12 cents per pound in 1932 to 10.80 cents in 1933; cotton income rose 57 percent throughout 1932, and government payments to cotton farmers totaled nearly $3 million. In 1934 Congress enacted compulsory crop control for cotton through the Bankhead Act, taxing the cotton of nonparticipating farmers. Cotton growers, in a referendum on crop control, overwhelmingly approved it. Through 1935 prices inched upward and acres in cultivation declined dramatically.

Crop controls for flue-cured tobacco developed after growers, angry about low opening market prices in 1933, pressured the AAA's Tobacco Section to persuade cigarette manufacturers to pay higher prices. To assure tobacco companies of their seriousness, AAA officials asked tobacco farmers to sign up for a 30 percent acreage reduction for 1934 and 1935. After 95 percent of tobacco growers complied, manufacturers eventually accepted a marketing agreement, promising a set price for the 1933 crop. The results were striking: that year, tobacco sold for 15.3 cents per pound compared to 11.6 cents in 1932. The AAA's tobacco program was successful, as the policy of scarcity drove prices up. For each year between 1934 and 1939, flue-cured tobacco farmers earned three times as much for their crop as they had in 1932.

In 1936 the U.S. Supreme Court declared the AAA unconstitutional. But farmers continued to consent to AAA tenets through referenda and participated in the decentralized, local administration of the program. Businessmen and politicians were enthusiastic allies, and in 1938 Congress reestablished many AAA programs, including marketing quotas. These congressional programs of 1938 brought crop control again to North Carolina tobacco farmers. Financed by general revenues rather than a tax on cigarette manufacturers (as was the first AAA), this scheme proved constitutional and growers overwhelmingly endorsed it.

Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA). Created to give direct cash relief for states and local governments to distribute, FERA funds between 1933 and 1935 provided relief payments to about 300,000 North Carolinians per month. Governor Ehringhaus established the North Carolina Emergency Relief Administration (NCERA) to distribute the federal funds, but local state welfare personnel often were FERA officers. Ehringhaus selected Annie Land O'Berry to direct the NCERA. She eventually administered the NCERA with 220 state office employees and about 2,000 county level assistants.

From 1933 to 1935 the NCERA administered relief remarkably free from corruption, spending almost $40 million in federal dollars and about $700,000 in local money. In addition to general relief, it funded public works, rural rehabilitation, education projects, a cattle program, distribution of surplus commodities, a fishing cooperative, and an urban vagrancy program.

In 1935 Congress stopped grants to states for direct relief, ending the NCERA, and in its place created work relief under the Works Progress Administration. From 1933 to 1935 about 10 percent of North Carolina's population was on relief, but these funds proved inadequate in both urban and rural areas, despite the millions of dollars that the FERA poured into the state. Per capita, North Carolina ranked a lowly forty-third nationally in FERA grants.

Public Works Administration (PWA). Created under the National Industrial Recovery Act in June 1933, the PWA sought to stimulate business activity by offering loans to private industry to build public works, also indirectly providing work relief. The PWA spent millions on constructing facilities at Fort Bragg in Fayetteville, improving the navigability of the Cape Fear River, and expanding the Blue Ridge Parkway. In 1934 the PWA allotment for North Carolina, including both federal and nonfederal projects, totaled just over $22 million. Former highway department chairman Frank Page and University of North Carolina engineering dean Herman G. Baity headed the Advisory Committee on Public Works for the state. By the end of the 1930s, the PWA in North Carolina had sponsored 903 projects at an estimated cost of $86.1 million and employed 6,938 workers.

Works Progress Administration (WPA). Intended as a permanent replacement for the FERA, the WPA concentrated on providing jobs for the able-bodied unemployed. Programs ranged from large construction projects to undertakings in social services, public health, conservation, education, the fine arts, and scholarly research. George W. Coan, former mayor of Winston-Salem, was appointed the first state administrator of the WPA in North Carolina in 1935. He was succeeded by Charles C. McGinnis in 1939.

Local conservative opposition to the WPA contributed to a relatively low amount of WPA spending in the state. Despite this, the WPA built 14,500 miles of highways, roads, and streets and about 700 bridges in North Carolina. Road projects concentrated on constructing secondary and "farm-to-market" routes and repairing and straightening existing roads. In towns, the WPA built sidewalks, curbs, gutters, and culverts and removed streetcar tracks. Workers raised nearly 1,000 new public structures, including city halls, municipal office buildings and garages, courthouses, and National Guard armories; they erected, renovated, or upgraded numerous schools, utility plants, water treatment plants, sewage treatment plants, reservoirs, airports, parks, school and municipal stadiums, and hospitals.

WPA North Carolina conservation projects included restoring oyster beds, building sand fences along the Outer Banks, planting more than 633,000 trees, restocking streams with trout and bass, and constructing levees, jetties, and breakwaters. In WPA sewing rooms, North Carolina women made more than 10 million garments and many Christmas presents for the needy. A WPA sewing room provided the first costumes for the outdoor drama The Lost Colony in Manteo. The WPA organized school lunch and breakfast programs, served 54 million school lunches, and organized adult education and literacy classes and nursery schools. WPA workers rebound more than 4 million library books in North Carolina and expanded public library service to 41 additional counties.

The WPA also employed artists, writers, and musicians in North Carolina and established several community arts centers. The WPA's Federal Writers' Project paid writers to conduct oral history interviews and compile a state guidebook. Scholars recorded traditional blues, bluegrass, gospel, and other music indigenous to the state. The Historical Records Survey published the nation's most comprehensive inventory of county records, and WPA workers cataloged manuscript collections at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Duke University, as well as other public and private collections of records and manuscripts. The WPA Federal Theater Project, started in 1935, hired professional artists to assist in community drama, building on the work of the Carolina Playmakers in Chapel Hill to develop a native drama. The Theater Project aided children's theater in Greensboro and Charlotte and adult community drama in Raleigh, Wilmington, Wilson, and Kinston. Through the Federal Art and Music Projects, hundreds of thousands of North Carolinians experienced art exhibits, took courses, and attended lectures, demonstrations, and performances. The North Carolina Symphony started as a program of the Federal Music Project in 1932.

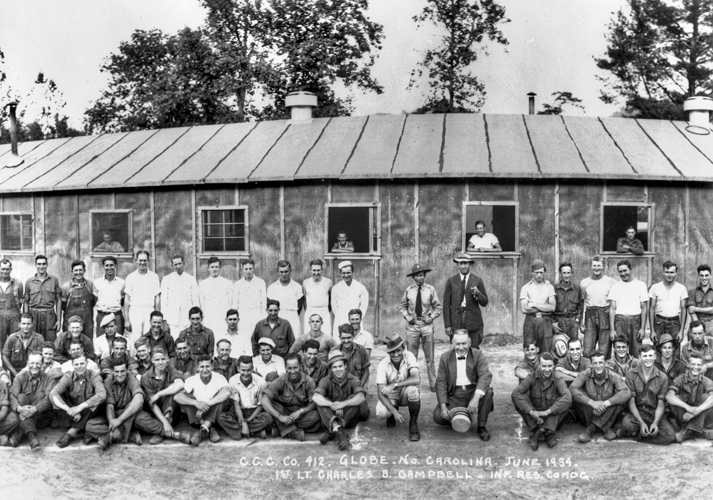

Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). One of the most remarkable and innovative New Deal programs, the CCC employed young men between the ages of 18 and 25 on conservation-oriented projects with emphasis on reforestation and erosion control. To expedite immediate enrollment, every state, and every county in that state, was assigned a quota of CCC enrollees based on population. North Carolina's quota ranged from 253 enrollees for Mecklenburg County to 9 for Dare County. The War Department screened enrollees and sent the eligible recruits to a military base, such as Fort Bragg, for a brief period of physical conditioning before assigning them to work projects.

The CCC had at least 66 camps in North Carolina, employing 13,600 men in 47 counties. One of the earliest camps was Camp John Rock, which operated in what is now the Pisgah National Forest from 1933 to 1936. The camp's major projects included a fish hatchery, fawn rearing, road building and maintenance, trail improvement, reforestation, and forest conservation. By the end of the program in July 1942, CCC workers had rehabilitated thousands of acres of ravaged land in North Carolina, including beach fronts. They also had either built or restored many recreational resources that established the state as a leader in tourism, including the Appalachian Trail, Great Smoky Mountains National Park, the Blue Ridge Parkway, national forests (such as Pisgah), state parks (such as Hanging Rock and Morrow Mountain), state forests, and the Cape Hatteras National Seashore.

National Youth Administration (NYA). The NYA was a student aid program organized in 1935 to keep young people in school. Initially, Charles E. McIntosh led the agency in North Carolina, but after August 1938 John A. Lang directed it. For the 1935-36 school year, the NYA provided $572,571 to assist an average of 5,907 students per month in 53 North Carolina colleges and 885 public schools. Students received part-time jobs, scholarships, and loans based on need. By 1941 NYA enrollments peaked at 15,000 students per month. North Carolina ranked second nationally in the number of participating schools and colleges. Lang, an energetic and capable director, was responsible for much of this success.

National Recovery Administration (NRA). In June 1933 Congress created the NRA to regulate wages, hours, and production to stimulate business recovery. Most North Carolina employers welcomed the assistance, with cotton textile executives in the forefront. Textile companies had cooperated with each other through a trade association since the 1920s, and the NRA strengthened efforts to bring order to the industry by establishing a textile code calling for a 40-hour workweek, a two-shift limit, and a minimum wage (lower in the South than in the North). Employers had to accept the right of workers to unionize and eliminate child labor, but they exercised power as principal administrators of the textile code through their trade association. By the end of 1933, use of the NRA textile code had produced only a modest increase in profits and wages. In 1934 opposition to the code mounted. Mill owners continued to take a tough stand against unions, and NRA collective bargaining rights remained illusory to textile workers in the state. By May 1935, when the U.S. Supreme Court declared the NRA unconstitutional, it had fallen short of its major goals for North Carolina's cotton textile industry.

The furniture industry, the state's third-largest commercial enterprise, had a similar relationship with the NRA. Conditions had been bad for the industry since the 1920s, and its leaders were eager for assistance; the NRA and manufacturers created and enforced a code with little difficulty. The program proved so helpful that in May 1935, when the Supreme Court ended the NRA, furniture executives sought its continuance.

The tobacco industry in North Carolina was not nearly as cooperative with the NRA as textile and furniture manufacturers had been. Cigarette companies, prosperous despite the Depression, did not need the NRA. They signed a temporary agreement in August 1933 but did not begin code hearings until a year later. The code was not completed until a few months before the NRA was invalidated.

Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). Created by Congress in 1933, the TVA was to be a bold experiment in the use of regional planning to achieve "the unified conservation and development" of the Tennessee River Valley. The Tennessee River, rendered barely navigable by reefs and shoals, flows 650 miles from Knoxville south into Alabama and then northwest to its juncture with the Ohio River at Paducah, Ky. Its entire watershed, comprised of tributaries extending into Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, and Virginia, came under the TVA's jurisdiction. The primary goals of the TVA were flood control, river navigation, and the generation of hydroelectric power. The authority also sought to enhance the valley's socioeconomic development by creating agricultural programs, such as those to promote soil conservation and improve fertilizers; facilitating the purchase of low-cost electrical appliances; and forming model communities with libraries, schools, and parks.

The TVA's impact in North Carolina can be seen in the far southwestern counties, where the authority built four dams in the 1930s and 1940s-the Hiwassee, Chatuge, and Appalachia Dams on the Hiwassee River and the Fontana Dam on the Little Tennessee River.

Social Security Act (SSA). The SSA, passed by Congress in 1935, not only introduced compulsory old-age and survivors' insurance but also provided federal funding for state unemployment compensation and a variety of state welfare programs. Under the act, when states established qualifying unemployment compensation programs, they would receive 90 percent of the federal payroll taxes collected in the state. States that did not have approved programs would lose the payroll taxes collected after 1 Jan. 1936. Since North Carolina's program did not meet the federal guidelines, a special session of the General Assembly was required to enact the needed legislation. Governor Ehringhaus was reluctant to call the special session and delayed action until December 1936, when the legislature created the state Unemployment Security Commission. The SSA also provided matching funds for state old-age pensions; state programs for blind, dependent children; and vocational rehabilitation. Initially, North Carolina did not contribute sufficient matching funds to receive the maximum payment allowed by the federal program, foreshadowing future problems in state-federal relations.

Educator Resources:

Grade 8: Great Depression. North Carolina Civic Education Consortium.

http://civics.sites.unc.edu/files/2012/04/GreatDepression.pdf

References:

Douglas Carl Abrams, Conservative Constraints: North Carolina and the New Deal (1992).

Anthony J. Badger, North Carolina and the New Deal (1981).

Badger, Prosperity Road: The New Deal, Tobacco, and North Carolina (1980).

John L. Bell Jr., Hard Times: Beginnings of the Great Depression in North Carolina, 1929-1933 (1982).

James S. Fackler and Randall E. Parker, "Accounting for the Great Depression: A Historical Decomposition," Journal of Macroeconomics 16 (Spring 1994).

Ronald E. Marcello, "The Politics of Relief: The North Carolina WPA and the Tar Heel Elections of 1936," NCHR 68 (January 1991).

Additional resources:

"Great Depression and North Carolina." North Carolina Museum of History. https://www.ncmuseumofhistory.org/workshops/The_1930s_in_North_Carolina/Session1.html

Records of the National Youth Administration, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. http://www.archives.gov/research/guide-fed-records/groups/119.html

State Archives of North Carolina. 2006. "Works Projects in North Carolina, 1933-1941." http://exhibits.archives.ncdcr.gov/wpa/

"Understanding the Great Depression." LearnNC. http://www.learnnc.org/lp/editions/nchist-worldwar/1.0

Image credit:

Emergency Relief Administration. 1934. "Women making mattresses in Wilmington in 1934." NCERA Photographs 1934-1936. State Archives of North Carolina. Box 144. Online at http://exhibits.archives.ncdcr.gov/wpa/women_1934_mattress.htm

1 January 2006 | Abrams, Douglas Carl; Blethen, H. Tyler; Hill, Michael; Jolley, Harley E.; Norris, David A.; Parker, Randall E.; Troxler, George W.