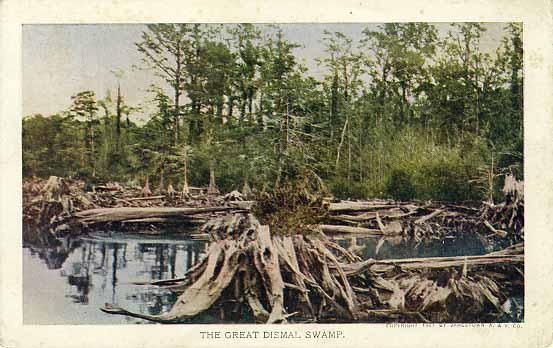

Great Dismal Swamp

The mysteriously and formidably named Great Dismal Swamp straddles the North Carolina-Virginia border only a few miles inland from the Atlantic coast. This region was referred to in correspondence as "dismal swamp" as early as 1715, and appears as Great Dismal Swamp on the 1733 Moseley map. The Great Dismal is a relatively young feature on the North American continent. Believed to be only about 10,000 years in age, the Great Dismal is a wet, forested mantle of peat above a Pleistocene-era ocean bed. Once a vast morass over 2,000 square miles in size, it is now a hemmed-in wilderness only a fraction of its original size, with approximately 175 square miles of it preserved as the Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge. As such, it is one of the most important black bear sanctuaries in the eastern United States and a breeding paradise for songbirds returning from South America, Central America, and the Caribbean each spring.

The mysteriously and formidably named Great Dismal Swamp straddles the North Carolina-Virginia border only a few miles inland from the Atlantic coast. This region was referred to in correspondence as "dismal swamp" as early as 1715, and appears as Great Dismal Swamp on the 1733 Moseley map. The Great Dismal is a relatively young feature on the North American continent. Believed to be only about 10,000 years in age, the Great Dismal is a wet, forested mantle of peat above a Pleistocene-era ocean bed. Once a vast morass over 2,000 square miles in size, it is now a hemmed-in wilderness only a fraction of its original size, with approximately 175 square miles of it preserved as the Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge. As such, it is one of the most important black bear sanctuaries in the eastern United States and a breeding paradise for songbirds returning from South America, Central America, and the Caribbean each spring.

American Indians hunted this area thousands of years before European settlement, when it was a great reach of open marsh. Archaeological digs have discovered countless artifacts-including bola weights, projectile points, tools, and weapons-that they used. Once the Ice Age ended and the climate warmed, the cold weather woods fell in succession to new forests, first of beech and birch, then of oak and hickory, and, finally, a wet stretch of cypress, gum, and juniper (Atlantic white cedar). Tribes like the Chowans and Chownocs were pushed off of these generational lands during the colonial period by white settlers.

The huge wilderness lying between the first two English settlements in the New World, the Great Dismal Swamp long held the attention of American settlers. William Byrd II, one of Virginia's commissioners for the 1728 boundary line survey expedition, wrote memorably of the swamp and its nearby inhabitants in both his official report, History of the Dividing Line betwixt Virginia and Carolina, and his rich, ribald daybook, The Secret History of the Line. These manuscripts circulated widely among Virginia's eighteenth-century social and business elite and influenced contemporary thinking about swamp drainage and agriculture, as well as the potential for a commercial shipping route through the Dismal Swamp to connect the Chesapeake and the Albemarle.

Young George Washington, who considered reclamation of the Great Dismal for farming a grand opportunity, successfully organized an agricultural syndicate, "the Adventurers for Draining the Dismal Swamp," in the 1760s. Washington Ditch, the first canal to penetrate the swamp, runs from what was once the "Dismal Town" settlement south of Suffolk down to Lake Drummond, the 3,100-acre natural lake at the swamp's center, discovered by and named for William Drummond, governor of Albemarle in the 1660s and subsequently a participant in Bacon's Rebellion in Virginia.

Rice and corn farming in the Dismal Swamp was only marginally successful, and, as the Dismal Swamp Company, Washington's adventurers moved into what would be an enormously profitable enterprise: timbering, felling cypress and juniper trees, riving shingles in the swamp, and shipping them out by flat boats called lighters. By 1795 the Dismal Swamp Company had cut over 1.5 million shingles in the Great Dismal Swamp. Though wooden shingles would eventually give way to tin and slate as popular roofing materials, vigorous swamp timbering operations employing railroads and, later, trucks would go on from after the Civil War until well into the twentieth century.

Rice and corn farming in the Dismal Swamp was only marginally successful, and, as the Dismal Swamp Company, Washington's adventurers moved into what would be an enormously profitable enterprise: timbering, felling cypress and juniper trees, riving shingles in the swamp, and shipping them out by flat boats called lighters. By 1795 the Dismal Swamp Company had cut over 1.5 million shingles in the Great Dismal Swamp. Though wooden shingles would eventually give way to tin and slate as popular roofing materials, vigorous swamp timbering operations employing railroads and, later, trucks would go on from after the Civil War until well into the twentieth century.

Between 1793 and 1814, a combine called the Dismal Swamp Canal Company realized Byrd's dream and dug a major shipping canal between Deep Creek, Va., and South Mills, N.C., connecting the Elizabeth River to the Pasquotank River and, thereby, creating an important water communication between the Chesapeake and the Albemarle. In 1812 the Canal Company dug the Feeder Ditch between Lake Drummond and the Dismal Swamp Canal in order to keep the canal's level at depths sufficient to float large craft, and the first real ship (a 20-ton craft bearing bacon and brandy from the Roanoke River) finally made passage through the Dismal Swamp Canal in June 1814.

Among important literary works set in the Great Dismal Swamp are Thomas Moore's wildly popular 1803 ghost ballad, "The Lake of the Dismal Swamp," a poem that engendered something of a nineteenth-century tourist business for the Great Dismal; Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's 1842 poem, "The Slave in the Dismal Swamp"; and Harriet Beecher Stowe's 1856 novel Dred: A Tale of the Dismal Swamp, her best-selling successor to Uncle Tom's Cabin. Stowe's work, in which a fictional slave runaway named Dred hides out in the swamp, was inspired by the true story of Southampton, Va., slave rebel Nat Turner and played upon the well-known fact that there was a large runaway-slave population living within the swamp for decades prior to the Civil War. Other noteworthy comments on the Great Dismal's evolving life and lore since Byrd's day include works by Johann David Schoepf, Edmund Ruffin, Frederick Law Olmsted, Porte Crayon (David Hunter Strother), and Alexander Hunter.

The Great Dismal Swamp also holds historical significance in the history of free people of color in North Carolina. In the 18th and 19th centuries, many multiracial families were recorded as living freely alongside white citizens in Gates County, NC. These free people of color's lineages route back to white settlers during the Colonial period, who then formed families with enslaved people and/or indigenous people that lived in the area, such as the Chowans or Chowanocs. Communities of free people of color in the Great Dismal Swamp area of Virginia were also recorded, and people from this area migrated to Gates County. According to court records and other primary sources, these families shared community resources -- such as churches, schools, and workplaces -- with their white neighbors and were less likely to experience physical punishment than in other areas of the state. These free people of color were often listed as "mulatto" under census records; this now-outdated term was applied to people who appeared to census-takers or may have identified as multiple races, like black, white, and/or indigenous.

On the anniversary of George Washington's birthday in 1973, Union Camp Corporation made a donation of its 49,100-acre holding in the swamp, land that is the core of today's 111,000-acre Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge. This grant, made through the Nature Conservancy to the U.S. Department of Interior's Fish and Wildlife Service, was the largest single land donation to that date ever made to the American people for wildlife preservation.

Educator Resources:

Grades K-8: https://www.ncpedia.org/great-dismal-swamp-k-8

References:

Bland Simpson, The Great Dismal: A Carolinian's Swamp Memoir (1990).

Charles Royster, The Fabulous History of the Dismal Swamp Company (1999).

Milteer, Warren E. “Life in a Great Dismal Swamp Community: Free People of Color in Pre-Civil War Gates County, North Carolina.” The North Carolina Historical Review 91, no. 2 (2014): 144–70. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23719092.

Paul W. Kirk Jr., ed., The Great Dismal Swamp (1979).

Additional Resources:

"George Washington," North Carolina Historical Highway Markers Program, http://ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?sp=search&k=Markers&sv=A-17

Dismal Swamp Canal Welcome Center Official Site: http://www.dismalswampwelcomecenter.com/

Moore, Mark Anderson. "Dismal Swamp Canal (map)." The Way We Lived in North Carolina. http://www.waywelivednc.com/maps/historical/dismal-swamp-canal.htm

Image Credits:

Wynn, Rebecca/USFWS. "Lake Drummond at Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge in Virginia." Digital photograph. August 2, 2006. From Flickr user: U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service - Northeast Region. https://www.flickr.com/photos/usfwsnortheast/4578425529/. (accessed May 15, 2012).

The Concessionaire, Jamestown Amusement and Vending Company, Norfolk, Va. "The Great Dismal Swamp." Postcard. 1907. Official Souvenier of the Jamestown Exposition. Courtesy of the North Carolina Museum of History.

1 January 2006 | Simpson, Bland