1850-1861: NC before the War

Originally published as "A Shadow Over Progress: 1850-1861"

by Harry L. Watson

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian, Fall 1996. Revised by NC Government & Heritage Library, May 2022.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

Related Entries: Transportation; Railroad; Piedmont; Education; Industry; Constitution History; Politics and Government; Civil War

By the end of the 1850s, North Carolina had become a very different place than it was in the 1810s and 1820s. State leaders were proud to say that “Old Rip” had awoken at last, and much evidence supported their boast.

Perhaps most obvious were changes in transportation. An extensive system of state-supported railroads was bringing improved transportation to many parts of the state, including distant western portions of the Piedmont. Plank roads were stretching out from market towns and railroad stations to reach farming communities and connect them with railroads and improved waterways.

No less important were education reforms. A simple but effective public school system was bringing education to thousands of children, and state schools and a mental hospital were beginning to address the needs of the blind, the deaf, and the mentally ill.

These changes led to better economic conditions for white people. Newspapers, banks, towns, and business activities were flourishing all across the state, in part because improved transportation had helped to spread prosperity and literacy to areas of the state that had been previously isolated from trade and frequent contact.

Changes to the Constitution

North Carolina’s government had changed during the period, too. These changes were prompted largely by amendments to the state’s constitution in 1835. First, popular election of the governor was introduced. And after decades of fighting for recognition, the west received equal representation in the legislature.

At the same time, national controversies during the presidency of Andrew Jackson had led to the development of two rival political parties, the Whigs and the Democrats. Campaigning and debating between the two parties became the focus of popular public events, where thousands of enthusiastic voters cheered for their favorite candidates.

The emergence of rival parties gave North Carolinians a clear choice between political alternatives. On the one hand, Whigs supported government efforts to promote progress and internal improvements as well as public schools and state charitable institutions and were not afraid to pay for these things by raising state taxes. Democrats, on the other hand, were not in favor of these changes, especially at the beginning of the period, and strongly opposed increasing state taxes to pay for reforms.

Slavery’s Ever-present Shadow

Despite its sudden record of reform, North Carolina in the 1850s was perhaps even more deeply committed to the institution of slavery than earlier in the century. Enslaved people were still regarded as very valuable property, and their enslavers had no intention of agreeing to sacrifice pieces of their wealth.

During the 1850s, sectional tensions were also increasing in America as northern and southern leaders fought harder and louder over the future of slavery. One powerful reform movement in the North called for the complete abolition of slavery in the United States. Most northern politicians, however, agreed with their southern counterparts that the federal government had no constitutional authority to abolish slavery in the existing states. But more and more of them felt they could prevent its growth in America’s newly gained territories in the West.

Any efforts to stop the growth of slavery provoked outrage from white southerners. Enslavers thought they were being treated unequally if their "human property" could not be taken to the territories just like any piece of a northerner’s property. In addition, they feared that a ban on slavery in these territories would be only the first step toward abolition everywhere.

The End of the Antebellum Era

In the North, a new political party began taking shape in 1854. It was called the Republican Party and was dedicated to keeping slavery out of the territories. Southern politicians warned that if the “Black Republicans” ever succeeded in electing a president, the South would secede, or leave the Union of states.

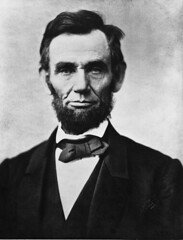

In 1860 a Republican president was elected—Abraham Lincoln. North Carolina’s governor, Democrat John W. Ellis, wanted to join with other southern states and secede from the Union immediately. But other state leaders asked for more time to see what Lincoln really would do.

*At the time this article was written, Harry L. Watson was a professor of North Carolina history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Additional Resources:

TeachingHistory. Org, Causing the Civil War: http://teachinghistory.org/history-content/beyond-the-textbook/23912

Rootsweb Ancestry, Civil War: http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~ncccha/memoranda/civilwar/civilwar.html.

North Carolina Civil War Sesquincentennial, Timeline: http://www.nccivilwar150.com/timeline/chronology.htm.

North Carolina History Project, Secession: http://www.northcarolinahistory.org/commentary/52/entry

North Carolina Civil War Tourism Council: http://www.nccivilwar.com/index.asp

University of North Caroilna at Chapel Hill Library, North Carolina Collection, North Carolina Civil War Image Portfolio. http://www.lib.unc.edu/ncc/pcoll/civilwar/

Image Credits:

Library of Congress. Photo taken November 8, 1863 and posted April 6, 2008"Abraham Lincoln- head & shoulders portrait. Located at http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/98504517/. Accessed March 5, 2012.

Library of Congress. "Andrew Jackson, President of the United States/ painted by W.J. Hubard ; C.G. Childs Lithr.; drawn by A. Newsam, pupil to C.G. Childs." Originally published between 1830-1834. Located at http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2009633805/. Accessed March 5, 2012.

Library of Congress. "Lincoln Museum Collection: Union and Liberty! And Union and Slavery!" Published 1864. Located at http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2008661670/. Accessed March 5, 2012.

1 January 1996 | Watson, Harry L.