Military Women

"Women Step Up to Serve"

by Hermann J. Trojanowski

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian. Spring 2008.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

During World War II, over 350,000 women from across the United States served in the military. More than 7,000 of these women came from North Carolina. As far back as the Revolutionary War, women had served with the military as nurses, cooks, and laundresses. However, these women were considered civilians and not military. It was not until World War I, when some women served in the U.S. Navy as “Yeomanettes,” that women were considered part of the military. Between 1917 and 1919, over 11,000 Yeomanettes performed mostly clerical duties to help relieve the navy’s labor shortage. Women, with the exception of nurses, would not again be part of the military until World War II.

In the late 1930s, while World War II raged in Europe and Asia, many government and military leaders in the United States believed the country would eventually be drawn into the fighting. Military planners feared the armed services would not have enough men to do the job. They believed that women in the military could contribute to the war effort. But many people were against the idea. Despite the opposition, in May 1941 Representative Edith Rogers, of Massachusetts, introduced a bill in the U.S. House of Representatives to create a women’s corps in the army. In May 1942 officials established the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC), giving women auxiliary but not military status. Auxiliary status meant that women did not receive the same pay, legal protection, or benefits as men. Females did get military status when the army disbanded the WAAC and established the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) in July 1943.

In the late 1930s, while World War II raged in Europe and Asia, many government and military leaders in the United States believed the country would eventually be drawn into the fighting. Military planners feared the armed services would not have enough men to do the job. They believed that women in the military could contribute to the war effort. But many people were against the idea. Despite the opposition, in May 1941 Representative Edith Rogers, of Massachusetts, introduced a bill in the U.S. House of Representatives to create a women’s corps in the army. In May 1942 officials established the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC), giving women auxiliary but not military status. Auxiliary status meant that women did not receive the same pay, legal protection, or benefits as men. Females did get military status when the army disbanded the WAAC and established the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) in July 1943.

Other military branches quickly followed the army’s lead. In July 1942 Congress established the U.S. Navy Women’s Reserve, better known by the acronym WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service). In November 1942 the U.S. Coast Guard Women’s Reserve was established. Its members were called SPARS, an acronym for the Coast Guard motto “Semper Paratus—Always Ready.” The Marine Corps Women’s Reserve was established in February 1943. Its members were simply called women marines.

The WASP (Women Airforce Service Pilots) group was established in August 1943 but did not have military status. These women ferried and flight-tested military planes, towed targets for male pilots to shoot at, and transported passengers and cargo from 1943 to late 1944. Thirty-eight of the 1,074 WASP lost their lives during the war. Because they were considered civilians, they were sent home at the expense of their families. WASP veterans finally received military status in 1977.

A common theme on recruitment posters for women was “free a man to fight.” Although women in the military did not serve in World War II combat, their service in other positions allowed many men to fight overseas. Women held jobs such as bakers, clerks, control tower operators, cooks, cryptographers, dental technicians, drivers, instructors, laboratory technicians, mechanics, nurses, parachute riggers, pharmacists, photographers, radiomen, spies, storekeepers, X-ray technicians, and more. They served all over the United States and sometimes in dangerous zones in Europe, North Africa, Southeast Asia, and the South Pacific.

Many North Carolina women who served during World War II have shared their military experiences through oral history interviews conducted for the Betty H. Carter Women Veterans Historical Project based in the University Archives and Manuscripts department at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Here are just a few of those stories.

Dorothy B. Austell, of Shelby, served as an undercover agent in the WAC from June 1943 to July 1946. One of her assignments was to find out why so many of the planes flying from Bear Field near Fort Wayne, Indiana, to England were crashing. She caught three men sabotaging gas tanks, which would have caused the planes to explode in midair. To this day, she remains sworn to secrecy about most of her wartime work.

Dorothy B. Austell, of Shelby, served as an undercover agent in the WAC from June 1943 to July 1946. One of her assignments was to find out why so many of the planes flying from Bear Field near Fort Wayne, Indiana, to England were crashing. She caught three men sabotaging gas tanks, which would have caused the planes to explode in midair. To this day, she remains sworn to secrecy about most of her wartime work.

Lucile Griffin Leonard, of Sanford, served as an army dietitian from 1943 to 1945. She recalled the trip across the north Atlantic Ocean on the Louis Pasteur, a converted British ocean liner. She had to share a two-person stateroom with 12 other women. They slept in bunk beds three decks high and shared a small bathroom designed for two people. Everyone slept in their fatigues, a type of uniform, and boots, in case they were attacked and had to abandon ship quickly. Leonard was stationed in North Africa and Italy. In 1944, while serving in Italy, she wrote her mother asking for candles, cake pans, and food coloring, so she could bake birthday cakes for the wounded troops.

Daphine Doster Mastroianni, of Monroe, served in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps from 1942 to 1945 as a surgical nurse stationed in New Zealand, Fiji, and India. While in the South Pacific, she became friends with Red Cross worker Joe Mastroianni. When the war ended, Mastroianni returned to his wife in New York. Doster returned to Arkansas and later to North Carolina, remaining single. In 1992, after Mastroianni’s wife died, he and Doster reconnected and married. They had seven wonderful years together before his 1999 death.

Lucille Ingram Pauquette, of Greensboro, joined the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve in March 1945. She was a postal clerk at Cherry Point Air Station until her discharge in June 1946. Pauquette had two brothers and two sisters who also were in the military during the war. Her parents were very proud to display five stars in their window, which let everyone know that they had five children in service.

Virginia Russell Reavis, of Onslow County, was a nurse in the Army Air Force from 1942 to 1945. In 1943 she became an air evacuation nurse and flew with wounded American soldiers and German prisoners of war back to the United States from England. One of the most horrible things that happened during her flying days was when her plane crashed during takeoff. The plane, hauling gasoline for General George Patton’s troops, crashed because of ice on its wings. As the plane skidded down the runway, it hit other planes lined up in a row, causing them all to catch on fire. Reavis scrambled off the plane as quickly as possible and gave first aid to the crew chief, who was badly injured and later died.

Davetter Butler Shepard, of Sampson County, served with the WAAC and WAC from 1943 to 1945. When her neighbors found out she was signing up, they accused her of going into the army just to have relationships with men. Of course, such gossip was untrue and did not keep her from joining the military. Shepard was a member of all– African American units at Camp Breckenridge and Fort Knox, Kentucky, where she worked in the motor pool driving a truck that carried supplies around the base. She recalled sending part of each fifty-dollar monthly paycheck home to help the rest of her family.

Millie Louise Dunn Veasey, of Raleigh, served in segregated African American units of the WAAC and WAC from 1942 to 1944 as a company and supply clerk. She remembered that most of the black community at the time disapproved of women joining the military, but that did not stop her. When her WAC unit got off the train in Scotland, some local residents had never seen black people, Veasey recalled, and said, “Look at the women in Technicolor.”

Anna Jean Coomes Woods, of western North Carolina, served in the WAVES from November 1943 to July 1946 in Classified Communications and Personnel. She recalled being too thin to pass the WAVES physical. She ate nothing but bananas and milk shakes for several days to gain weight. Woods did finally join the WAVES, in spite of only gaining one pound and becoming sick from all the bananas and shakes.

The women who served during World War II faced challenges. Often their parents, other family members, and friends did not want them to join the military because of slander and rumor campaigns, which accused women who joined to be of low morals. Many people felt women who served in the military would not make good mothers. The military often treated them like schoolgirls instead of mature women. Females were held to higher educational, moral, and skills standards than men. African American women faced not only gender but race discrimination.

All the women interviewed for the Betty H. Carter Women Veterans Historical Project are proud to have served. They joined the military for a number of reasons—to work, to learn new job skills, to travel, to better their lives, to earn more money, and to contribute to the war effort. Their time in the military made them more self-confident and independent, and it opened up new opportunities. After the war, many former servicewomen took advantage of the GI Bill to further their educations and enter careers that had previously been closed to them. They rightly considered themselves trailblazers and pioneers for the women who later served during the Korean, Vietnam, and Gulf wars, and in the modern military.

*At the time of the publication of this article, Herman J. Trojanowski was assistant university archivist at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. At that time he had interviewed more than 85 women veterans for the Betty H. Carter Women Veterans Historical Project. Access the project’s Web site at http://library.uncg.edu/dp/wv/.

Visit these biographies of military women from North Carolina in NCpedia -- they include links to recorded audio of oral history interviews

Grace Collins Boddie, WAVES (WWII): https://www.ncpedia.org/boddie-grace-collins

Gladys Lunsford Dimmick, WAVES (WWII): https://www.ncpedia.org/dimmick-gladys-lunsford

Barbara Courntey Gouge, SPARS (WWII): https://www.ncpedia.org/gouge-barbara-courtney

Gladys Moore Pittman, WAAC/WAC (WWII): https://www.ncpedia.org/pittman-gladys-mclean-moore

Martha Armstrong Silver, WAVES (WWII:) https://www.ncpedia.org/silver-martha-carolyn-armstrong

Lillie Lenora Crocker Stanley, WAVES (WWII): https://www.ncpedia.org/stanley-lillie-lenora-crocker

Connie Marie Badgett Steadman, U.S. Air Force, https://www.ncpedia.org/steadman-connie-marie-badgett

Almyra Maynard Watson, U.S. Army Nurse Corps (WWII-1960s): https://www.ncpedia.org/watson-almyra-maynard

Juanita Hartense Hamilton Webster, U.S. Army Nurse Corps (WWII): https://www.ncpedia.org/webster-juanita-hartense-hamilton

Eleanor Thompson Wortz, WASPS (WWII): https://www.ncpedia.org/wortz-eleanor-elaine-thompson

Correction to this article: Lucille Pauquette had one brother and three sisters who joined the military during World War II.

-- Kelly Agan, N.C. Government & Heritage Library

Image credits:

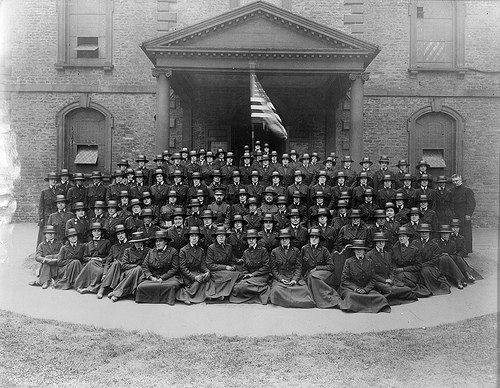

"Army Nurses, Base 65, World War I." Image No. N.53.16.1409. From the Albert Barden Collection, North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh, NC, USA.

Hamblet Col J. E. https://www.flickr.com/photos/judgerock/4971377032/.

1 January 2008 | Trojanowski, Hermann J.