WWI: Women volunteers

On the outskirts

During World War I, North Carolina women made major contributions to the war effort by working in a variety of volunteer organizations. One of the largest was the American Red Cross, a relief organization that provides care and help to civilians and soldiers. One Red Cross worker with ties to North Carolina was Suzanne Breckinridge Hoskins.

During World War I, North Carolina women made major contributions to the war effort by working in a variety of volunteer organizations. One of the largest was the American Red Cross, a relief organization that provides care and help to civilians and soldiers. One Red Cross worker with ties to North Carolina was Suzanne Breckinridge Hoskins.

Like most young women volunteering for service, Hoskins probably had visions of nursing sick and wounded soldiers near the front line trenches. But the Red Cross had other plans for her. She was assigned to work with the Children’s Bureau in France. Arriving in France in October of 1917, Hoskins settled into her work as chief nurse at Évian-les-Bains, a resort on the border of France and Switzerland on the banks of Lake Geneva. She described her accommodations to her sister:

We are on the beautiful lake, in a quaint little town of Evian. It is a summer resort, the wonderful baths of Evian. . . . The A.R.C. has taken over this, oh really splendid property—Hotel Chatillet. The hotel is to be the hospital and the [staff] cottages the nurses homes. . . . We will not open before [the middle of] November. The refugees come in at certain times—one thousand at a time—then there is a rest—and then again they come—a thousand again—old men, women, and children—poor, poor children.

The refugees were sent to Hoskins’s hospital from German prisons and war-torn regions of France and Belgium. Many of the children had lost their homes, had been separated from their parents, and had only the clothes they were wearing.

Drawings were often a part of Hoskins’s letters to her sister. On November 24, 1917, she described one of the children she helped: “Another, a fat little gentleman of five—very much rolled up in an immense tippet—He very determinedly blinked away his tears and when I got him unpacked, I said ‘Well—how do you do, sir?’ He dimpled up at me and said, ‘Oui Madame!’ very heartily.”

Hoskins and her staff provided these children with basic medical care as well as warm clothes and a clean bed. “Our part of the game is this, here on the border to get all sick and diseased children and to care for them—to keep disease from the entire country of France—we have scarlet fever, diphtheria, measles, mumps, chicken pox, tuberculosis, pneumonia, and many feet tired out.”

In addition to her work at Évian-les-Bains, Hoskins worked at La Choux where she was responsible for setting up a children's hospital. She and the staff helped care for 175 children. When she first arrived there, the head of the hospital, Dr. Lamb, wanted to examine every child thoroughly. Hoskins wrote her sister of the event:

Now, there were no cards or numbers made out, no numbers on beds and nobody was sure which child was which. So we lined up 90, had 90 physicals, 90 cards made out which took from 10 am to 6 pm. The next day we did 85, and then 175 beds were numbered and names assigned. Then came the dentist and his assistant who worked for three days from 10 until 5, until every tooth was examined, filled, pulled or cleaned. Then the throat specialist and his assistant came to check the children. If this were not enough, there were three meals a day out under the trees, the line-up at 8:30 each am for throat examinations, toothbrush drill, etc. Getting a place like this [organized] is some job!

Hoskins and the nurses she supervised performed an important job in caring for the children of war-torn France. These children needed the skilled nursing care that they could provide. Hoskins wished to be at the front and often commented on this in letters to her sister. But she never got a chance to work with wounded soldiers before she returned home in 1919. After the war was over, Hoskins wrote an article for Ladies Home Journal based on her experiences. She titled it “On the Outskirts: The Diary of a War-Baby Nurse.” The title makes it seem that Hoskins felt she had been on the fringes of war work and that her job had not been that important. Yet the sick, cold, and hungry children she helped would have strongly disagreed with her. Hoskins and the nurses who worked with her played a small but vital role in helping France and Belgium survive the destruction of World War I.

At the time of this article’s publication, Vivian Lea Stevens was curator of collections at the Museum of American Frontier Culture in Staunton, Virginia. She formerly held the same role at the Greensboro Historical Museum.

Resources for Educators:

Beginnings of the American Red Cross Primary Source Set and Teaching Guide, Digital Public Library of America

Additional resources:

"Finding Aid for the Anna Maria Gove Collection, 1864 - 1952." University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Jackson Library. http://library.uncg.edu/info/depts/scua/collections/manuscripts/ead/Mss002.xml

"Annie Bryant Robey Papers, 1918-1919." University of North Carolina Charlotte, J. Murrey Atkins Library. http://library.uncc.edu/manuscript/ms0225

North Carolinians and the Great War. Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries. https://docsouth.unc.edu/wwi/

Wildcats never quit: North Carolina in WWI. NC Department of Cultural Resources. http://www.history.ncdcr.gov/SHRAB/ar/exhibits/wwi/default.htm

"World War I." ANCHOR. https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/world-war-i

WWI: NC Digital Collections. NC Department of Cultural Resources.

WWI: Old North State and the 'Kaiser Bill.' Online exhibit, State Archives of NC. http://www.history.ncdcr.gov/SHRAB/ar/exhibits/wwi/OldNorthState/index.htm

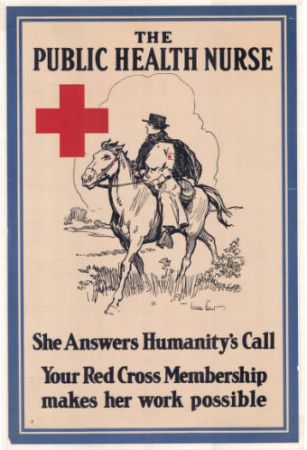

Image credit:

Grant, Gordon. "The Public Health Nurse." American National Red Cross. State Archives of North Carolina. Call no. MilColl.WWI.Posters.3.37. Online at https://digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/the-public-health-nurse/557913.

1 May 1993 | Stevens, Vivian Lea