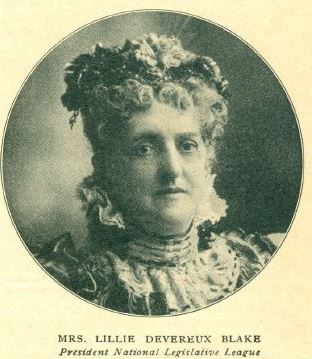

Blake, Lillie Devereux

12 Aug. 1835–30 Dec. 1913

Lillie Devereux Blake, author and suffragist, the daughter of George Pollock and Sarah Elizabeth Johnson Devereux, was born in Raleigh, a descendant of two famous churchmen of New England. Although she was named Sarah Johnson for her mother, her father called her Lily (Lillie) because of her unusual fairness, and she continued through life as Lillie. Her father, a descendant of colonial Governor Thomas Pollock, inherited Runiroi Plantation in Bertie County and lived there from 1827 to 1837. The plantation was in a "rich, low savanna lying on the Roanoke River not far from the Great Dismal Swamp." To escape the summer heat and threat of malaria, the family frequently traveled north in the spring, and George Pollock Devereux died en route in 1837. Lillie and her mother continued their journey to Connecticut; soon after arriving there a second daughter, Georgiana, was born. The Carolina plantation was sold and the Devereuxs made their home in New Haven.

Lillie Devereux Blake, author and suffragist, the daughter of George Pollock and Sarah Elizabeth Johnson Devereux, was born in Raleigh, a descendant of two famous churchmen of New England. Although she was named Sarah Johnson for her mother, her father called her Lily (Lillie) because of her unusual fairness, and she continued through life as Lillie. Her father, a descendant of colonial Governor Thomas Pollock, inherited Runiroi Plantation in Bertie County and lived there from 1827 to 1837. The plantation was in a "rich, low savanna lying on the Roanoke River not far from the Great Dismal Swamp." To escape the summer heat and threat of malaria, the family frequently traveled north in the spring, and George Pollock Devereux died en route in 1837. Lillie and her mother continued their journey to Connecticut; soon after arriving there a second daughter, Georgiana, was born. The Carolina plantation was sold and the Devereuxs made their home in New Haven.

Family connections in New England and many acquaintances of prominence led to an active social life; Mrs. Devereux had the dubious distinction of refusing to entertain Charles Dickens on his American tour because he had no letter of introduction. Lillie and her sister attended the Misses Agthorp's school, where they took the usual lessons in music, dancing, and drawing, followed by instruction in mathematics and philosophy and "other courses pursued by young men in the sophomore and junior classes at Yale," under the tutelage of a young theological student from the university. Lillie was introduced to society at seventeen. According to her diary, she realized at sixteen "the position of my sex, feeling with indignation and humiliation . . . the role assigned to women." This conclusion remained with her, although she lived for several years a social life at watering places in Saratoga, Niagara, and West Point and visited New Orleans, Havana, and Philadelphia.

Lillie Devereux was twice married. Her first husband, Frank Geoffrey Quay Umstead, was the father of her two daughters, Elizabeth Johnson Devereux and Katherine Muhlenberg Johnson. He died, and she later married Grinfell Blake of Maine.

Suffering from ennui following confinement with her first daughter, Lillie began writing as a recreation. Thus began a literary career that became her chief means of support on the death of her first husband. Her spare time was spent in reading the classics and contemporary novels. She started writing a novel (Rockford ) while publishing more lucrative short stories under various pseudonyms—Essex, Charity Floyd, Di Fairfax, Violet, and Tiger Lily. Her publications in Harper's Weekly, the Saturday Evening Post, the New York Leader, the Sunday Times, and many other periodicals earned a small monthly income and allowed an independence, fulfilling her resolution to "owe her position to her own exertions and not to any man's protection." In 1861 she moved to Washington, D.C., upon receiving commissions to print letters from the national capital to the New York Evening Post, the New York World, and the Philadelphia Post. Again she moved among such distinguished personalities as Dr. Verdi (nephew of the composer), Governor Andrew Curtin of Pennsylvania, and Anthony Trollope. She visited the White House, describing people and dress at the presidential levees. Her description of President Lincoln noted his "kindness and sadness of expression." The War Press commissioned several serials and short stories, demanding "themes of blood and love." On a second stay in Washington in 1864, she renewed her visits to the capitol, meeting another native North Carolinian, Andrew Johnson, and being received by General Ulysses Grant. Still reading voluminously, "not even scorning dime novels," she was delighted with Darwin, Spencer, and Huxley. She wrote "patiently and continuously" for more than thirty years in fifty different magazines. By 1882 she had written approximately five hundred stories, articles, speeches, and lectures and five full-length novels. She wrote and spoke in the high-flown speech admired in her day.

Lillie's second career began in 1869, when she joined the woman's suffrage movement. Descriptions of early suffragists are found in her diary. Her first glimpse of Susan B. Anthony was recorded with amazement at Miss Anthony's attire of a "bloomer costume of printed dotted silk !" The early suffragists offered their contemporaries the choice of "Hoops and Stays or Blouses and Freedom"; the latter represented convenience, health, or a gesture of freedom. Lillie herself was described as beautifully dressed, but at about the age of fifty she discarded the fashionable, heavily-boned, wasp-waisted corsets, in favor of the "more healthful dress for females" encouraged by Dr. Lewis, a popular health adviser.

Lillie's second career began in 1869, when she joined the woman's suffrage movement. Descriptions of early suffragists are found in her diary. Her first glimpse of Susan B. Anthony was recorded with amazement at Miss Anthony's attire of a "bloomer costume of printed dotted silk !" The early suffragists offered their contemporaries the choice of "Hoops and Stays or Blouses and Freedom"; the latter represented convenience, health, or a gesture of freedom. Lillie herself was described as beautifully dressed, but at about the age of fifty she discarded the fashionable, heavily-boned, wasp-waisted corsets, in favor of the "more healthful dress for females" encouraged by Dr. Lewis, a popular health adviser.

After visiting the Woman Suffrage Headquarters and meeting Mrs. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and others prominent in the movement, Lillie decided, "They're ladies," and began to participate actively. Former society friends and relatives rejected her in her new-found field. Characteristically, she became completely involved. She studied and labored long and hard, "practicing gymnastics to expand my chest and strengthen my voice, exercising myself in elocution and studying politics, history and the laws, so I could deal with the questions of the day intelligently." A new social life evolved around an evening a week devoted to entertaining people important in literary and political life—Francis Brett Harte, Professor Goodyear, L. Bradford Prince (later governor of New Mexico), and Mrs. Frank Leslie, who made a financial success of her husband's publishing house.

Lillie played a prominent part in the National Woman's Suffrage Association and the American Woman's Suffrage Association. Her writing was channeled to the movement and included a contribution to the Woman's Bible, a publication based on Biblical criticism and ecclesiastical history, proving that there was "no explanation for the degraded status of women under all religious, and all so-called 'Holy Books.'" The book created a sensation when it was printed in 1895, with widespread coverage in New York papers. The clergy declared it the work of Satan.

Lillie—by then Mrs. Blake—was a natural organizer. She worked on the national level, but her chief success was in the state of New York. She championed the working people, particularly the women. Fettered for Life, or Her Lord and Master, published at her own expense, was an immediate success, selling thirteen hundred copies on the first day. An active lobbyist in the legislature, she pled for school suffrage, equality of property rights, women factory inspectors, women physicians in hospitals and psychiatric institutions, and police matrons. A Committee on Legislative Advice was organized with her assistance, to help other suffragists; her leaflet of instructions was printed in the Woman's Journal. She succeeded in seeing the passage of legislation granting women the first vote in state elections and the right to become trustees of schools; with the support of Governor Theodore Roosevelt and over "the persistent opposition of the New York Police Department," a bill was passed providing for police matrons. Further legislation allowed women to retain citizenship following marriage to a foreigner, and her final accomplishment was the enactment of an equality of inheritance law by the New York assembly. Eventually the suffragist movement was accepted by "ladies of leisure," who were quickly recruited by Mrs. Blake. They met at the Plaza Hotel and made Sherry's their headquarters. Holidays and celebrations—Columbus Day and the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893—were used to further their goals. Pilgrim Mother's Day was celebrated, in imitation of the New England society for male descendants, by a dinner at the Plaza with important speakers, writers, lawyers, and authors.

At a 1907 testimonial dinner, Lillie Devereux Blake was recognized by a gift of one thousand dollars, which she spent on a trip to Europe. There she met with suffrage leaders in London. The following year she stopped writing and retired to a sanatorium, where she died. "Lillie Devereux Blake, Champion of Woman Kind," was memorialized the next spring in the Church of the Messiah.

References:

Katherine Devereux Blake and Margaret Louise Wallace, Champion of Women: The Life of Lillie Devereux Blake (1943).

DAB, vol. 3 (1929).

Eighty Years and More: Reminiscences of Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1898).

Additional Resources:

Margaret Mordecai Devereux Papers, 1837-1856 (collection no. 02492-z). The Southern Historical Collection. Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. http://www.lib.unc.edu/mss/inv/d/Devereux,Margaret_Mordecai.html (accessed April 12, 2013).

Short bio in Britannica: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/68784/Lillie-Devereux-Blake

Lillie Devereux Blake, Grace Farrell, 2010: https://www.worldcat.org/title/lillie-devereux-blake-retracing-a-life-erased/oclc/368046185&referer=brief_results

Lillie Devereux Blake Papers, 1847-1986 (bulk 1847-1913), Missouri History Museum Archives: http://www.mohistory.org/files/archives_guides/Blake_Lillie_Devereux_Papers.pdf

Lillie Devereux Blake : retracing a life erased, Grace Farrell, 2002: http://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/ocm49226345

"Our Forgotten Foremothers." by Lillie Devereux Blake. Publication: Eagle, Mary Kavanaugh Oldham, ed. The Congress of Women: Held in the Woman's Building, World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, U. S. A., 1893.. Chicago, ILL: Monarch Book Company, 1894. pp. 32-35. Available from UPenn Libraries: http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/eagle/congress/blake.html

Image Credits:

Lillie Devereux Blake, The Feminist Press, CUNY

Lillie Devereux Blake. Courtesy of Lincoln Memorial University. Available from http://www.lmunet.edu/museum/exhibit/vex7/images/10300A97-7F5E-48D9-B2AB-095936564233.jpg (accessed April 12, 2013).

1 January 1979 | Crabtree, Beth G.