White, John

fl. 1577–93

See also: John White, Research Branch, NC Office of Archives and History; Art of John White

John White, colonizer and artist, who was closely associated between 1585 and 1590 with the area that became North Carolina, has not been firmly identified, but arms granted to him in 1587 are those of the White family of Truro, Cornwall, in England. One John White of this family was a member of the Haberdashers Company of London but died in 1585. He might possibly have been the uncle of our subject—a John White who was trained as an artist-craftsman and became a member of the Painter-Stainers Company of London by 1580.

John White, colonizer and artist, who was closely associated between 1585 and 1590 with the area that became North Carolina, has not been firmly identified, but arms granted to him in 1587 are those of the White family of Truro, Cornwall, in England. One John White of this family was a member of the Haberdashers Company of London but died in 1585. He might possibly have been the uncle of our subject—a John White who was trained as an artist-craftsman and became a member of the Painter-Stainers Company of London by 1580.

During the late 1560s John White was a parishioner of St. Martin Ludgate in London—a parish dominantly populated by haberdashers. On 7/17 June 1566 he married Tomasyn Cooper. The next year, on 27 April/7 May, their son Thomas was baptized. On 9/19 May 1568 John White's daughter Elinor, who was destined to become the mother of the first child of English parentage to be born in the New World, was baptized. Near the end of that year, on 26 Dec. 1568/5 Jan. 1568/69, the infant Thomas was buried, and White seems to have left the parish shortly afterwards—at least he does not appear in any of the parish records after that date. The next reference to a John White who might be he is in January 1578/79. On Twelfth Night, A Maske of Amazons was presented at Richmond Palace for Queen Elizabeth. One John White and one Boswell were paid by the Office of Revels under the category of painters for the parcel gilding of two armors used by two Knights of the Masque. A William Boswell, painter, had been a parishioner in St. Martin Ludgate at the same time as John White.

John White may have accompanied Martin Frobisher on his expedition to Baffin Island to look for gold in 1577. If so, he was probably present as observer and recorder (although no narrative of his is extant); he drew pictures there of one of Frobisher's ships and an Eskimo in a kayak, a vigorous impression of an encounter between English and Eskimos. He certainly painted front and rear views of the man, woman, and child brought back to England. It appears that these pictures (and perhaps others) were engraved (conceivably by White himself) in a small volume of illustrations published in 1578 of which no copy survives, but for which we are fortunate in having several original drawings and a number of derivatives.

White is first found mentioned by name in connection with the Roanoke voyages on 11/21 July 1585 in a ship's boat in convoy with Sir Richard Grenville and a small exploration party. Crossing Pamlico Sound to Pomeioc on the mainland, he drew the Indian village and a number of its inhabitants. Later, going on to Aquascogok and then to Secotan a little farther south, he did the same there.

In 1584 Walter Raleigh's reconnaissance party had identified Roanoke Island as a suitable place to establish a settlement. An expedition under Grenville left England on 9/19 Apr. 1585 to plant a military post and a base for a survey of the coast and the interior. In July it landed from the Tiger at what is now Roanoke Island, where, before the end of August, Ralph Lane supervised the construction of crude cottages and a fort. John White and Thomas Harriot, the mathematician and navigator in Raleigh's employ, were members of the expedition.

Harriot remained with the Lane colony for its eleven-month tenure, during which time he recorded the physical, natural, and human resources of the area. John White drew, and subsequently painted, many components of the same resources. We can imagine the two men compiling from their field notes and sketches large illustrated summaries in fulfillment of the task assigned to them.

White had begun to prepare himself by drawing picture-plans of temporary camps made in Puerto Rico on the way over and putting on paper a number of plants, animals, birds, and fish seen in the Caribbean and along the sea route to the Outer Banks. From the base at Roanoke Island the pair proceeded to compile illustrated information on their Indian neighbors, ultimately penetrating up Albemarle Sound and probably the Chowan and Roanoke rivers. To improve their coverage, they possibly paid further visits to the southern parts of Pamlico Sound, working their way along the shores of the Outer Banks. Harriot must have compiled map sketches as he went, with White helping him to assemble them into districts as a base for the first map of the area. At the same time he must have drawn the animals, crustaceans, fish, birds, and plants that came to their notice. It must have been at this time that Harriot made notes about clay, sand, minerals, and the possible uses of timber, as he later published a little book with such information.

In the Indian villages, both men carefully observed plants grown for food and tobacco for smoking. Harriot, and perhaps White as well, tried to learn the language and gain some impression of Indian concepts. After the initial investigation of the area, Sir Richard Grenville and his fleet departed for England, leaving behind a contingent of settlers who were charged with the responsibility of conducting further explorations under the direction of Governor Ralph Lane. Harriot certainly remained with the colony for its full tenure, and White may have—although there is no evidence to support his remaining or his leaving. All of his extant paintings could have been made during the preliminary explorations. Because these paintings do not include renderings of the fort and houses on Roanoke Island, there is reason to believe that some, or even most, of White's work has been lost. If he did remain with the colony for the full time, then he certainly would have made more drawings, perhaps even of the area near the Chesapeake Bay. A small group of colonists wintered near the southern shore, and White and Harriot would logically have been included.

Certainly by the summer of 1586, when the colonists returned to England with Sir Francis Drake, Harriot had compiled copious notes and collected numerous natural history specimens. The transfer of men and materials from the shore to Drake's ships during a violent storm was haphazard. Some of Harriot's samples were lost; some of White's sketches could have been lost, and that would account for the absence of pictures of the fort, cottages and many plants, Indians, and natural history specimens. Even so, once back in England Harriot proceeded to write A briefe and true report of the new found land of Virginia, which he planned to publish in support of the 1587 enterprise but held over, for some reason, until 1588. It was not until the latter year that a White-Harriot collaboration took shape when Theodor de Bry obtained materials from both of them to put together his America, Part I (1590), uniting Harriot's tract with engravings of a selection of White's Indian drawings. Published in four languages, it spread their names throughout Europe, although Harriot received most of the credit.

White put together a selection of his drawings as a gift to some important person (and this is what survives of his original work in the British Library). Many of his own copies were recopied in his household. By this process a number of his subjects were saved that otherwise would have been lost.

John White was one of the few men who returned from Roanoke Island with the belief that English people could settle alongside the Indians and live in North America a better life than most of the middling sort—craftsmen, tradesmen, mildly Puritan Protestants not too happy about bishops, small farmers, and the like—could at home. It was for this reason that he promoted a plan to bring out a new kind of settler, colonists who would go as families and would be self-sufficient in a short time even if, in the end, the land would, he believed, make them moderately rich. Raleigh sympathized with White and granted him a substantial area to the south of Chesapeake Bay where the city of Raleigh could be created. A society, called "The Governour and Assistants of the Cittie of Ralegh in Virginea," was constituted in 1587. A seal and arms were made for it; the governor (White himself) and the twelve assistants (even the Portuguese pilot, Simão Fernandes) were all granted coats of arms. It is likely that Raleigh paid for all of this. The enterprise did not go smoothly but well enough to be viable. More were willing to join the colonists later.

Departure was rather late (8/18 May), with arrival at the Outer Banks not until 22 July/2 August. At Roanoke Island they were to leave Manteo as the new lord or high chief of the area under the English Crown and pick up the holding party left by Grenville when he arrived in late summer of 1586 and found the first colony gone. There was no one left alive on the island, however. But Fernandes was determined that there should be: he told White he would not take the colonists to Chesapeake Bay, their real objective, and they must stay on Roanoke Island. His reasons were obscure. Was it because he wanted to get even with White for their disagreements during the voyage, or was it, as he alleged, that he wished to hurry to the Azores to catch stragglers from the Spanish flota, or even was it because he knew what had happened between 1570 and 1572 when the Spanish and the Powhatan Indians were in conflict and that it was not safe for them to go within reach of this tribe?

Despite all of this, White set his settlers to restoring the cottages and the fort (the embankment around it had been flattened). At a personal level he had problems; his daughter Elinor, wife of Ananias Dare, one of the assistants, was pregnant and on 18/28 August gave birth to the girl christened Virginia on 24 August/3 September, while Manteo formally accepted Christianity and was installed as lord of Roanoke. Clearly, White envisaged Roanoke as a place where his people might stay, even winter, before going on to their final home near Chesapeake Bay. But his associates were not happy; they did not have enough supplies to last very long, and they may have been anxious that their final site should be known in England. Only White, they assured him, could bring them aid and reinforcements quickly. He allowed himself to be persuaded. He said farewell, forever as it turned out, to his family and set sail for England on 28 August/7 September, reaching Southampton on 8/18 November after a wretched voyage.

It would seem that he had taken every reasonable precaution in anticipation of his return. The main body of colonists were to move when they were ready "fiftie miles within the maine"—that is, into the territory of the Chesapeake tribe. If, when he arrived and they were gone, signs were agreed as to whether they were well or in distress, and the name of their destination was to be incised on tree trunks. In England Raleigh met White twelve days after his arrival and assured him that aid would be sent with all speed. But in truth this was not easy to arrange. A single vessel could scarcely risk the direct route west from Madeira that Grenville had taken in 1586 or a run through the Caribbean alone now that war at sea was general. Finally, Raleigh made up his mind. White must wait and go over with a new expedition in 1588. This was not destined for Roanoke Island or the city of Raleigh but to find a site for a base, probably farther south, from which active war could be carried into the Spanish Indies. Grenville, once again, was to command, but though he was almost ready with his fleet in March 1588, he delayed long enough to be stopped by the queen and sent to join the great naval force preparing to resist the long-heralded but now imminent Spanish Armada. Raleigh and Grenville did all they could for White: he was to face the ocean and the enemies there in two small pinnaces, the Brave and the Roe, with fifteen or sixteen new colonists and what stores he could cram in. Not far from the Azores, the Brave became involved in a fight with a stronger French privateer and was boarded and robbed.

Arriving back in England wounded and penniless, White found the Roe also a victim of pirates but otherwise unharmed. His miserable voyage left White helpless, while the great sea fight in the English Channel went on and while all sailings overseas were stopped until the queen could assess what shipping she needed for her counterblow the following year. It was apparently William Sanderson, Raleigh's business manager, if we may so call him, who eventually arranged some new backing for White. Also providing support was a syndicate of sympathizers including Sanderson and Richard Hakluyt, whose Principall navigations within a few months would make public the story of the Roanoke voyages. Why, somehow, relief could not be sent after the formation of this group on 7/17 Mar. 1589 we cannot tell, as a few privateers did get permission to operate in the Caribbean. But its influence was not enough to get White to sea that year.

It was only in 1590 that Sanderson could offer any hope of getting one of his ships, the Moonlight, to sea. She was to sail under the protection of three privateering vessels belonging to the merchant prince, John Watts, but they were ready before the Moonlight, and so White thrust himself on board the Hopewell and was grudgingly promised transport to Roanoke Island. He spent some time on board until finally the Moonlight joined them off Cuba, having made her way there safely (and was no doubt carrying stores for the colonists). Eventually the Hopewell, having sent home a valuable Spanish prize, agreed to go north with White. The vessels arrived off Hattorask (roughly what is now Oregon Inlet) on 15/25 August. But because of high seas and strong winds, the first attempt to get ashore was disastrous. Captain Spicer of Sanderson's Moonlight and nearly half his crew were drowned when their boat overturned. Eventually, one of the Hopewell's boats got White ashore. After an absence of three years, the governor finally returned to the settlement on Roanoke Island where he had left his colony.

The colonists were gone; so were both fort and cottages, and instead a stout barricade enclosure, suitable as a defended camp, remained. In it were some deserted guns and pieces of metal. The remains of White's personal belongings were found buried "in the ende of an olde trench, made two yeares past by Captaine Amadas"; they had been dug up by Indians. His armor was rusted, and his maps and pictures were damaged. More encouraging, however, were signs indicating that all was well, and the word Croatoan cut on one of the chief trees or posts of the palisade entrance showed that the resident party, which had waited as long as it could, had gone south to Croatoan where Manteo's village was. This was good news, but White pleaded in vain for transportation across the sound to where he expected to find them. The sea was too rough; the sailors were anxious to get away. White sailed home in the Moonlight, with her crew further depleted after an accident on board. Almost by a miracle she got back. White was at Plymouth on 24 Oct./3 Nov. 1590 after his last voyage, as no one would take him out again, even though the syndicate remained nominally in existence in London.

Further action rested with Raleigh alone, and he decided he wanted none taken. His patent would expire in 1591 if he had not planted a permanent colony in America. White, though he had not found the colony, had brought home news that it was alive. This assumption was to keep Raleigh's control over English voyages to North America alive until 1603. In due course White was packed off to Ireland, perhaps as a freeholder in the Munster plantation, another bigger English colony. If so, he was settled at Newtown in the Great Wood of Kilmore on the lands of a prominent landholder, Hugh Cuffe, some nine miles above Edmund Spencer at his little castle at Kilcolan. Here he lived, possibly with wife and family, and from here he wrote to Hakluyt an account of his last voyage, with a covering letter dated 4/14 Feb. 1592/93. He could only say that all his plans for an American colony had come to an end. "And wanting my wishes, I leave off from prosecuting that whereunto I would to God my wealth were answerable to my will." He could only commend the relief "of my discomfortable company, the planters in Virginia" to God's help. This is his last word.

The colonists, it would appear, did live on. Raleigh promised to stop to see them in 1595 on his way back from Guyana but did not do so. Cautiously, using small trading vessels from about 1599 onward, he tried to get word of them: an expedition of 1602 reached the Outer Banks but too far to the south. Ironically, they probably were heard of when two Indians were brought to London who possibly could tell of them, but his patent had expired and he was a prisoner in the Tower in 1603. The belief persisted that the colonists had survived and may have strengthened the Virginia Company's determination to colonize Chesapeake Bay, where they might have been of help. But it appears that as Christopher Newport rounded Cape Henry in April 1607, Powhatan, busy building his power over the peoples around the bay, struck at the Chesapeake tribe and their English associates of nearly twenty years' standing and killed them all except a few who got away to the Chowan River, where the local Indians kept them out of sight of parties from Jamestown searching for them. Powhatan later admitted his complicity in their slaughter. The Lost Colony, however, passed into myth and legend and became the stuff of fiction, not history, though its shadow kept the name of White and of his daughter and granddaughter alive for Americans, especially North Carolinians.

The colonists, it would appear, did live on. Raleigh promised to stop to see them in 1595 on his way back from Guyana but did not do so. Cautiously, using small trading vessels from about 1599 onward, he tried to get word of them: an expedition of 1602 reached the Outer Banks but too far to the south. Ironically, they probably were heard of when two Indians were brought to London who possibly could tell of them, but his patent had expired and he was a prisoner in the Tower in 1603. The belief persisted that the colonists had survived and may have strengthened the Virginia Company's determination to colonize Chesapeake Bay, where they might have been of help. But it appears that as Christopher Newport rounded Cape Henry in April 1607, Powhatan, busy building his power over the peoples around the bay, struck at the Chesapeake tribe and their English associates of nearly twenty years' standing and killed them all except a few who got away to the Chowan River, where the local Indians kept them out of sight of parties from Jamestown searching for them. Powhatan later admitted his complicity in their slaughter. The Lost Colony, however, passed into myth and legend and became the stuff of fiction, not history, though its shadow kept the name of White and of his daughter and granddaughter alive for Americans, especially North Carolinians.

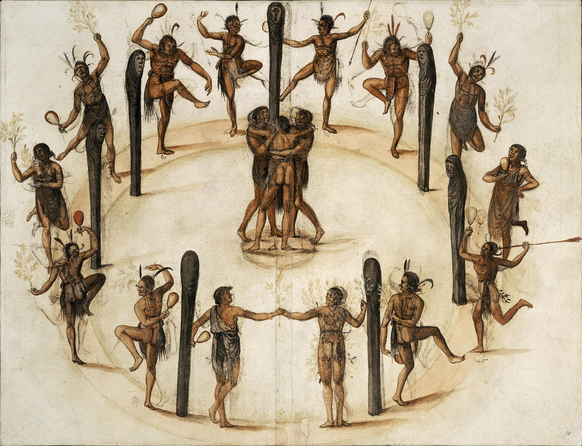

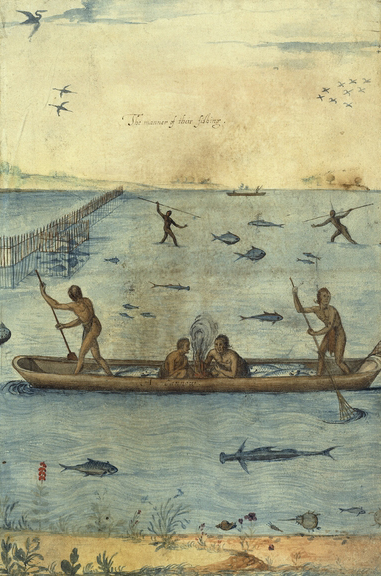

As an artist, White's reputation has grown slowly but surely in the present century, though more particularly since publication of fine versions of his drawings in 1964. It appears that he had some artistic training, revealing some Mannerist influence, and he learned much from Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, the artist-explorer of French Florida who settled in London and had his own collection of Indian scenes to make and remake. Paul Hulton, the leading authority on White's paintings, described his "carefully finished water-colour drawings" as "more spontaneously naturalistic than anything known by an English artist at this period." He considered White's "quality so marked as to be more revolutionary than anything known by an English artist at this period." White drew rough outlines in black lead and applied his water-colors directly to the paper, without a ground, strengthening them with body color and with touches of gold, silver, and white. His use of perspective was intermittent: often he used a half plan, half bird's-eye view for his landscapes, but most of his figure drawings of Indians were formed with a rare fidelity to life, and so they have an authority that no other early pictures of North American Indians had or were to have for a very long time. They are consequently priceless ethnographic documents, detailing artifacts and clothing with care and understanding, and showing the two village communities he drew as living entities.

His natural history specimens are also remarkably true to life, especially birds and fish, though he had nothing like Le Moyne's expertise and taste in drawing plants and flowers. Thomas Penny, an early zoologist, used versions of White's swallowtail butterfly, fireflies, and other insects, and John Gerard included the milkweed in his Herbal (1597). White also discussed with him the virtues of sarsaparilla roots (Smilax pseudochina). Some of his bird drawings came to Hakluyt as well. White's presentation volume has survived; his own collections have not. John White wrote well and at times with a simple eloquence. In his narratives of the 1587, 1588, and 1590 voyages he portrays himself as an enthusiast for colonization and a moderately effective organizer of his enthusiasm into action. He clearly could inspire people like himself with a vision of a fruitful life in a wholly new environment. But he had insufficient experience of business or, indeed, of the harshness and intrigues of life at sea. He failed to make a sufficiently strong impression on the London merchants with whom he dealt to rally them into adequate action on his behalf. At sea, too, he was pushed around by the more violent and self-centered seamen. As a governor he would no doubt have been paternal and constructive, while he had an instinctive affinity with the Indian that few Englishmen were to show. But he may not have been strong enough to stand up against adversity or opposition.

His return to England in 1587, whatever the pressures on him, was a fatal mistake—his primary duty was to stay with the colonists. His failures to return to relieve them were due to misfortune and bad luck, but he did not stand up to Raleigh once it became clear—as it must have done after his return in 1590—that Raleigh considered his interest would best be served by not relieving the colony, for the time being at least, because the discovery in or after 1591 that the colonists were all dead would rob him of his stake in North America that he was determined to hold. White, it might seem, always gave way under pressure. He was, however, more farsighted than most of his contemporary enthusiasts for American colonization in believing that a small, mixed community of men, women, and children stood a better chance of establishing itself in America alongside its own inhabitants than a larger, mainly male colony based on military strength and bound to conflict with Indian rights. He thus has a significant place in English colonial relations with the New World.

References:

Theodor de Bry, America, Part I (1590).

Richard Hakluyt, Principall Navigations (1589) and Principal Navigations, vol. 3 (1600).

Thomas Harriot, A brief and true report of the new found land of Virginia (reprint, 1972).

Paul Hulton, The Watercolor Drawings of John White (1965) and The Work of Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, 2 vols. (1977).

Paul Hulton and David B. Quinn, The American Drawings of John White, 2 vols. (1964), and "John White and the English Naturalists," History Today 13 (1963).

Ivor Noël Hume, The Virginia Adventure (1994).

David B. Quinn, England and the Discovery of North America, 1480–1610 (1974) and Ralegh and the British Empire (corrected ed., 1973). Lebame Houston and Olivia Isil, Manteo, N.C., have contributed to this entry new information that they found on several research trips to England in the late 1980s.

Additional Resources:

G. Moran, Michael G. "John White (d. 1593)." Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. http://encyclopediavirginia.org/White_John_d_1593 (accessed February 4, 2013).

"John White Drawings/Theodor De Bry engravings." Virtual Jamestown. http://www.virtualjamestown.org/images/white_debry_html/introduction.html (accessed February 4, 2013).

"A New World: England’s first view of America." The British Museum. http://www.britishmuseum.org/about_us/news_and_press/press_releases/2007/a_new_world.aspx

Image Credits:

White, John. "The manner of their fishing." North America, about AD 1585-93. © Trustees of the British Museum. http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_objec...(accessed February 4, 2013).

White, John. "A festive dance." North America, about AD 1585-93. © Trustees of the British Museum. http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_objec...(accessed February 4, 2013).

White, John. "The manner of their attire and painting them selves." North America, about AD 1585-93. © Trustees of the British Museum. http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_objec...(accessed February 4, 2013).

1 January 1996 | Quinn, David B.