The Black Pioneers Loyalist Company was one of the few all-Black military companies during the American Revolution. The company was composed of fifty to one hundred formerly enslaved people. They escaped enslavement from the Cape Fear River Region of North and South Carolina and the James River Region of Virginia. Significant cities from which many Black Pioneers fled enslavement included Portsmouth and Norfolk in Virginia, Charleston in South Carolina, and Wilmington in North Carolina.

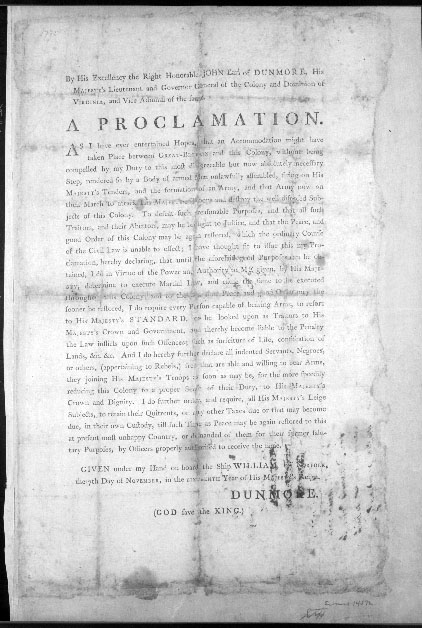

The Pioneers were created during the 1776 British siege of Wilmington. On February 9, 1776, the British sloop Cruizer moved up the Cape Fear River to attack Wilmington, and the people that lived there evacuated. As more British ships arrived from Boston under the command of Sir Henry Clinton, British soldiers and ships attacked Wilmington, along with its riverside homes, and private plantations. With the city burning and people evacuating, many enslaved people used this as an opportunity to escape to freedom behind British lines. Many of them fled to British military camps for safety because of British promises of emancipation offered in Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation, issued in 1775. In April 1776, Clinton and a subordinate officer, George Martin, organized a group of freedom-seeking people from North Carolina, South Carolina and Virginia into a military company. This military company was called The Black Pioneers and was made up of formerly enslaved and free black people. They were soldiers who served British and Loyalist forces as “pioneers.”

The Black Pioneers’ activities varied, but the roles they served were usually dangerous. They served as scouts, raiders, custodial staff, and military engineers until the end of the war. Members of the Black Pioneers were given little training or protection during their jobs. Such tasks included building huts, bases, or defenses. They also cooked and cleared land for soldier camps. They were also responsible for digging outhouses and latrines. When the company was first created, its members died often. This was most likely due to exhaustion from overwork, or exposure to harsh winter climates.

The Black Pioneers were managed by Clinton and traveled with his company throughout the war. They traveled across North America supporting the Loyalist cause. After British forces captured Charleston on May 12, 1780, Clinton went to New York. The Black Pioneers traveled with them there, and to many other places in New England as well as Philadelphia. The company remained in New York until the war ended in 1783.

At the end of the war, Patriot leaders stated that all “property” was to be returned and demanded the return of enslaved people that had escaped. However, the Black Pioneers (and other Black Loyalists) had successfully provided essential services to the British monarchy during the Revolution. And according to the multiple royal proclamations, they were no longer property. Sir Guy Carleton, leader of the British forces, refused to return people to their enslavers. Instead, they were evacuated to Nova Scotia, Canada to live as free Black people.

British soldiers and Loyalists, including the Black Pioneers, were evacuated from New York after the British defeat. Many members of the Black Pioneers were documented at the evacuation of New York. According to the Book of Negroes, approximately 3500 Black and African people migrated to Canada as part of this evacuation. Their names were recorded, along with their status as a Black Pioneer, in the British government’s Book of Negroes. The Book was the list of all Black people that left New York for Nova Scotia with the British.

Some members of the Black Pioneers fled enslavement in North Carolina. Murphy Steele had been enslaved by Stephen Daniel in Brunswick County. Abraham Leslie had been enslaved by Parker Quints in Upper Town Creek (near Edgecombe County). And Thomas Peters had been enslaved by William Campbell in Wilmington (New Hanover County).

After leaving New York, the Black Pioneers were disbanded, like many other British military companies. Many of the group’s members, like Steele and Peters, worked as social activists after the group was dissolved. They fought for the rights of Black people in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, Canada. Peters also continued his work by helping Black Canadians return to (and receive land in) Africa. He helped found the modern nation of Sierra Leone, located in West Africa.

Glossary:

- Loyalist: Supporters of the British monarchy in the colonies during the American Revolution.

- Emancipation: To release someone from something, usually slavery.

- Pioneer: A person who does something before many others do it. Used here to describe a type of military role.

References:

“A History of the Black Pioneers.” The On-Line Institute for Advanced Loyalist Studies. December 2000. https://web.archive.org/web/20230524170048/http://royalprovincial.com/mi... (accessed July 25, 2024).

“An Introduction to North Carolina Loyalists Units.” The On-Line Institute for Advanced Loyalist Studies. December 2000. https://web.archive.org/web/20220925082237/http://www.royalprovincial.co... (accessed July 25, 2024).

“Black Loyalists, 1783-1792.” African Nova Scotians in the Age of Slavery and Abolition. Nova Scotia Archives. July 2024. https://archives.novascotia.ca/africanns/results/?Search=&SearchList1=2 (accessed July 25, 2024).

“Black Loyalist Communities in Nova Scotia.” Nova Scotia Museum, Virtual Museum of Canada. 2001.https://web.archive.org/web/20071111014753/http://museum.gov.ns.ca/black... (accessed July 25, 2024).

“Black Pioneers Formation Orders: On board the Pallissar Transport, Cape Fear River, ye 10th May 1776.” The On-Line Institute for Advanced Loyalist Studies. December 1999. https://web.archive.org/web/20230524170048/http://royalprovincial.com/mi... (accessed July 25, 2024).

“Book of Negroes.” African Nova Scotians in the Age of Slavery and Abolition. Nova Scotia Archives. July 2024. https://archives.novascotia.ca/africanns/book-of-negroes/ (accessed July 25, 2024).

“Book of Negroes: ‘Fortune — A Free Negro.’” African Nova Scotians in the Age of Slavery and Abolition. July 2024. Nova Scotia Archives. https://archives.novascotia.ca/africanns/archives/?ID=29&Page=200402035 (accessed July 25, 2024).

Hannigan, John, Ph.D. “Service with the British Army.” National Park Service. October 12, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/john-hannigan-patriots-of-color-paper-2.htm (accessed July 25, 2024).

“Map of Black Loyalist Settlements.” Nova Scotia Museum, Virtual Museum of Canada. 2001. https://web.archive.org/web/20080724201119/http://museum.gov.ns.ca/black... (accessed July 25, 2024).

Ncurrie. “Record of the Week: The Book of Negroes.” Rediscovering Black History. February 5, 2015. National Archives and Records Administration, Say It Loud. https://rediscovering-black-history.blogs.archives.gov/2015/02/05/rotw-the-book-of-negroes/ (accessed July 25, 2024).

“Petition on Behalf of the Black Pioneers.” African Nova Scotians in the Age of Slavery and Abolition. August 20, 1784. Nova Scotia Archives. https://archives.novascotia.ca/africanns/archives/?ID=32 (accessed July 25, 2024).

St. G. Walker, James W. “Blacks as American Loyalists: The Slaves’ War for Independence.” Historical Reflections / Réflexions Historiques 2, no. 1 (1975): 51–67. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41298659 (accessed July 25, 2024).

“The Black Pioneers.” Black Loyalists: Our History, Our People. Canada’s Digital Collections. https://blackloyalist.com/cdc/story/revolution/pioneers.htm (accessed July 25, 2024).

Wilson, Ellen Gibson. The Loyal Blacks. New York: Capricorn Books. 1976.

Additional Resources:

“Black Loyalists Heritage Site.” Black Loyalist Heritage Center. https://blackloyalist.com/birchtowns-historical-site-2/ (accessed July 25, 2024).

Cahill, B. “The Black Loyalist Myth in Atlantic Canada”. Acadiensis, vol 29, no 1, 76. Autumn 1999. https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/Acadiensis/article/view/10801 (accessed July 25, 2024).

Dunnen, Kevin Den. “Black Loyalists and the Promise of Freedom.” ArcGIS StoryMaps, October 27, 2023. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/fa9a1a0adcfe4297b1088ac7bdc8b144 (accessed July 25, 2024).

Hollingsworth, S. The Present State of Nova Scotia : With a Brief Account of Canada, and the British Islands on the Coast of North America. https://archive.org/details/McGillLibrary-rbsc_lc_present-state-of-nova-scotia_lande00450-17225/page/n19/mode/2up (accessed July 25, 2024).

“Life During the American Revolution: Resources for Students and Educators: Black Experience of the American Revolution.” New York Public Library. Jul 12, 2024. https://libguides.nypl.org/c.php?g=1176173&p=8696798 (accessed July 25, 2024).

“Loyalist Trails 2013-21.” The United Empire Loyalists' Association of Canada. May 26, 2013. https://uelac.ca/loyalist-trails/loyalist-trails-2013-21/ (accessed July 25, 2024).

“The Philipsburg Proclamation.” June 30, 1779. https://www.ouramericanrevolution.org/index.cfm/page/view/p0422 (accessed July 25, 2024).