By winter 1864 the Union was poised to strike North Carolina from several vantage points. General William T. Sherman completed his March to the Sea in late December and turned his attention northward to the Carolinas. The Union high command also turned their attention to the Cape Fear region, particularly Fort Fisher and Wilmington, long neglected in favor of numerous failed attempts to subdue Charleston, which the Union viewed as the very seat of dominion secession. With the Army of Northern Virginia entrenched around Petersburg and Richmond, the Union realized they could force them out if they could cut off their main source of supplies through Wilmington.

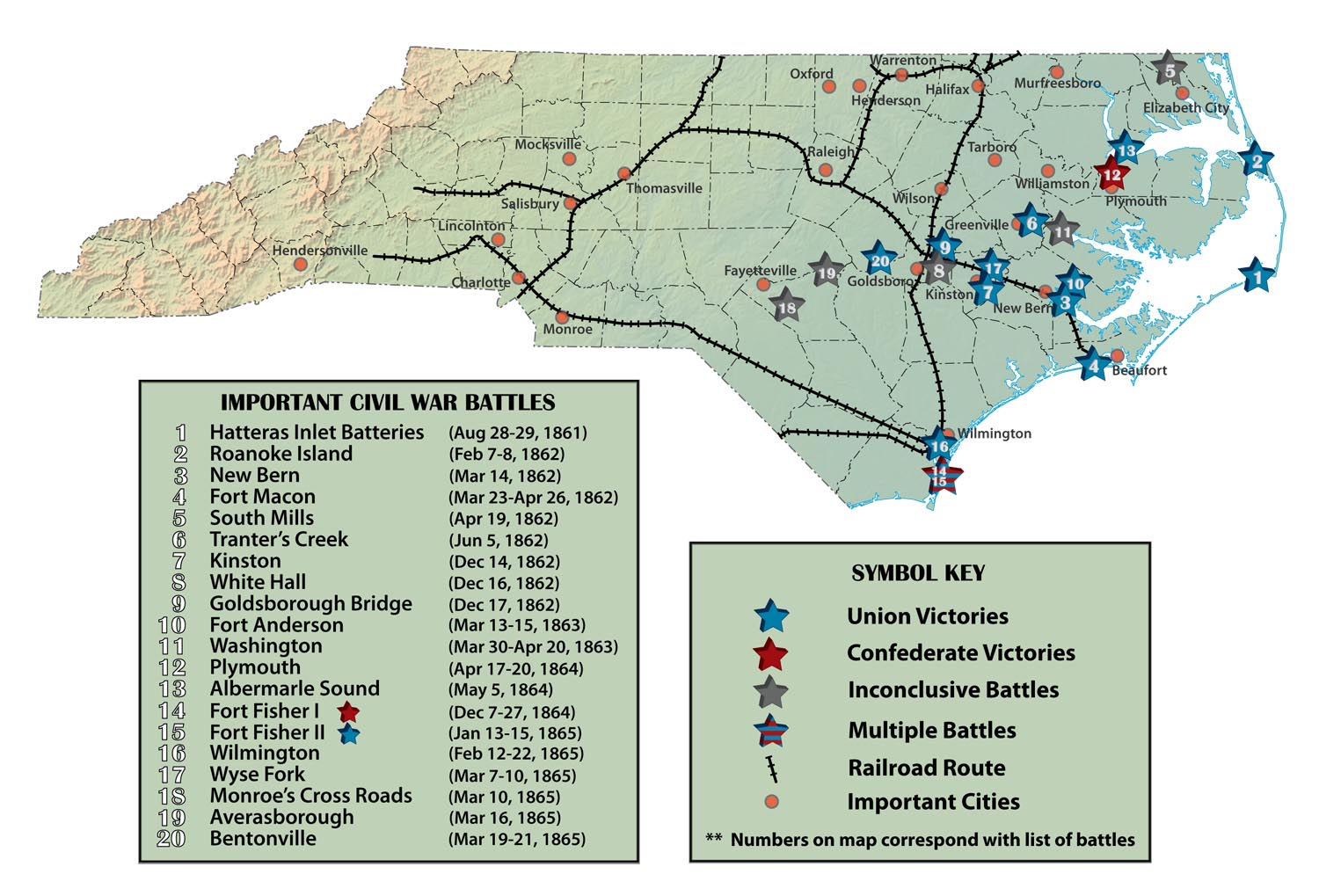

In December 1864 the Union assembled a joint operation to attempt the reduction and capture of Fort Fisher. The plan called for the navy to bombard the fort, while the army landed a force to the north. Once the naval bombardment had effectively damaged the fort, the infantry would begin their assault. Commanding the expedition were Admiral David Dixon Porter and General Benjamin Butler. The First Battle of Fort Fisher took place on Christmas, with the navy opening its bombardment on December 24. On Christmas Day, as Porter anxiously awaited the ground attack on the fortification, Butler’s force instead retreated. The navy’s artillery fire had been largely ineffective and had not dismounted enough of the fort’s heavy guns to allow for an assault without heavy casualties. The weather had taken a turn for the worse and Butler also learned that General Robert F. Hoke’s division of 6,000 men had arrived in Wilmington and would soon be to his rear. Porter was incensed and blamed the failed attempt to take the fort on Butler’s lack of courage and mismanagement.

Following the Christmas debacle, the Union high command replaced Butler with General Alfred Terry and sent the expedition back to Fort Fisher for a second attempt. On January 13, 1865 the Second Battle of Fort Fisher began as the navy once again shelled the fort. Gunners on board all of the vessels in the fleet were ordered to concentrate their fire on the fort’s gun chambers in order to maximize the bombardment’s effectiveness. The plan of attack this time also made provisions for a naval landing party, supported by marines to be put ashore and attack the fort from the beach, at its northeast bastion. Terry would land his force north of the fort as before and make the ground assault, while putting troops in position to protect his rear from possible reinforcements from Wilmington. Manning this defensive line were United States Colored Troops, African-American soldiers, under the command of General Charles J. Paine. After two days of bombardment, many of the fort’s land face guns had been disabled, making an assault much easier. As sailors and marines stormed the northeast bastion of the fort, they were slaughtered by murderous Confederate gunfire from inside the fort. However, as many of the Confederate troops and officers were distracted by the sailor’s charge, Terry’s main assault breached the western salient of the fort at the River Road sally port, giving the Union a foothold inside the fortification. The Union soldiers methodically fought their way across the length of the land face and down the interior of the fort. Both General W.H.C. Whiting and Colonel William Lamb, Fort Fisher’s commander, were wounded and captured. The fort was overwhelmed and forced to surrender. Though some Confederate sailors were able to escape across the Cape Fear River, most of the fort’s garrison was captured. Meanwhile, General Hoke’s troops waited at Sugar Loaf, north of Fort Fisher, for an order to attack the Union troops from behind. Instead they received orders from General Braxton Bragg in Wilmington to retreat, leaving Fort Fisher to its fate. On January 15 Fort Fisher was officially in Union hands and the lifeline of the Confederacy was cut.

Following the fall of Fort Fisher, the Union Navy entered the Cape Fear River. The fortifications at the mouth of the river were abandoned and troops relocated to Fort Anderson on the opposite side and upriver from Fort Fisher. The Union split its forces into two wings, one which moved north up the peninsula from Fort Fisher toward Wilmington and the other crossing the river to capture Fort Anderson. General Jacob D. Cox and General John Schofield led a 6,000 man force against Fort Anderson, which was defended by less than half that number. Operations against Fort Anderson were also assisted by navy gunboats as had been the case against Fort Fisher. The vessels had to proceed with caution, in order to avoid the line of torpedoes or underwater mines that had been placed in the river by the Confederates. On February 17 and 18 Union gunboats shelled Fort Anderson. The fort’s commander, General Johnson Hagood began evacuating his troops on the night of February 18, knowing he could not defend the position. Fort Anderson fell into Union hands on the morning of February 19. While Union gunboats shelled artillery batteries on the riverbank south of Wilmington, the army fought skirmishes at Town Creek in Brunswick County and at Forks Road, just outside of Wilmington. These were the Confederates’ last efforts to defend the port city. Bragg ordered the city evacuated and Wilmington fell to Union forces on February 22.

As Union forces were securing their hold on Wilmington, General William T. Sherman was marching into North Carolina from the south, having just captured Columbia, South Carolina. In the meantime, Jacob Cox’s force was sent to New Bern to make an advance against Goldsboro. Cox started for Goldsboro on March 6 with approximately 13,000 troops. Confederate resistance was met two days later at Wyse Fork, just east of Kinston. On the first day of battle, the Confederates held their ground and Robert F. Hoke captured most of the 15th Connecticut regiment. After two more days of battle, the Confederate forces were ordered to evacuate Kinston and move to Goldsboro to join forces with General Joseph Johnston. The ironclad ram CSS Neuse was ordered into action to cover the evacuation. The gunboat spent most of March 11 firing on the Union army. Following the evacuation, the crew of the Neuse scuttled the gunboat and retreated behind the army, leaving Kinston to the Union.

On March 11, as the Confederates were evacuating Kinston, Sherman marched into Fayetteville and took possession of the arsenal after minimal resistance. The retreating Confederates removed most of the arms, munitions, and equipment prior to leaving the town, and Sherman ordered that the arsenal be razed. From Fayetteville, Sherman continued his march, having split his 60,000 man force into two wings. The right wing of Sherman’s army encountered Confederate resistance from General William J. Hardee’s Corps on March 15-16 at the Battle of Averasboro. This resistance simply delayed the left wing of the Union force, which eventually caught up with the rest of the army at Bentonville.

The delaying action at Averasboro was exactly what General Joseph E. Johnston, commanding all Confederate forces in North Carolina, desired. Knowing that Sherman’s army was nearly twice the size of his own, Johnston hoped to catch the Union force divided. Johnston positioned his troops along the Goldsboro Road, near the village of Bentonville and awaited the arrival of one wing of Sherman’s powerful army. The Battle of Bentonville was fought March 19-21 and was the largest battle fought in the Old North State. Initially, the Confederates broke through Union lines, but failed to completely crush the enemy. When the right wing of the Union army caught up with their comrades, it ensured Johnston’s defeat. The armies battled for two more days, but on March 21, Union forces under General J.A. Mower advanced to within 200 yards of Johnston’s only avenue of retreat. Though the Confederates managed to drive them back, Johnston withdrew his force from the field that evening and retreated to Smithfield. Sherman did not pursue, but rather continued to Goldsboro and re-supplied his weary troops. The Battle of Bentonville was the largest, but not the final military action in North Carolina.

From March 28 through April 26, 1865, Union General George Stoneman led a destructive raid through western North Carolina and southwestern Virginia. The main purpose of the raid was to disrupt the North Carolina Railroad and Piedmont Railroad. On March 28, troops in Boone burned the jail and destroyed the county records, while at Patterson, a cotton mill was burned and stores of bacon and corn were confiscated. From April 3-10, Stoneman’s force was in southwestern Virginia, but they returned to North Carolina on April 10. In order to hit multiple targets, Stoneman frequently divided his force. On April 10, the towns of Salem and Winston were surrendered and spared from harm. The Piedmont Railroad bridge over Reedy Fork was burned, as was another bridge over Buffalo Creek. The 3rd South Carolina Cavalry was routed and a portion of the North Carolina Railroad was cut. Finally, at High Point, a depot containing 1,700 bales of cotton was burned. One of Stoneman’s main targets was the town of Salisbury because of the Confederate prison located there. Salisbury was captured after token Confederate resistance on April 12, and on April 12-13 the public buildings and military stores there were burned.

Stoneman turned back to the west and arrived in Statesville on April 13. Confederate stores, a depot, and the offices of the Iredell Express were burned. On April 16, a detachment of Stoneman’s force occupied Lincolnton, crossed into South Carolina, and burned a railroad bridge over the Catawba River. Stoneman returned to Tennessee on April 17, via Blowing Rock and Boone, while sending General Alvan Gillem on to Asheville. On April 18, Gillem encountered Confederate resistance near Morganton, but was able to overcome it and occupy the town. Gillem was confronted by a much stronger Confederate force led by General James G. Martin at Swannanoa Gap on April 20. Knowing that Martin’s force would prove difficult to defeat, Gillem rerouted his men to Rutherfordton, crossed the Blue Ridge, and approached Asheville via Hendersonville. Having heard of the ongoing negotiations between Generals Joseph E. Johnston and William T. Sherman, Martin’s men refused to fight. On April 24, General Martin met with General Gillem and arranged for Gillem’s force to be supplied out of Confederate stores and have safe passage through Asheville, back to Tennessee. Stoneman’s Raid ended on April 25 when Gillem’s force occupied Asheville. The next day, Gillem left the occupying force and returned to Tennessee.

Aside from Stoneman’s Raid, major military hostilities ceased once General Robert E. Lee’s surrender became widely known. Raleigh was surrendered to Union forces on April 13. Generals Sherman and Johnston met in April at the farm of James and Nancy Bennett near Durham Station to work out the details of Johnston’s surrender. This agreement was finalized on April 26, 1865, thus officially ending the Civil War in North Carolina.

The final shots of the war in North Carolina had yet to be fired. There was some skirmishing in the mountains of western North Carolina following Stoneman’s Raid. Union Colonel George W. Kirk raided Franklin and Waynesville in early May 1865. His detachment of cavalry engaged a small Confederate force belonging to Thomas’ Legion, a military organization partially made up of Cherokee tribesmen from the mountains. This action was of little consequence, but it was the last military action of the war in North Carolina.

Source Citation:

"North Carolina as a Civil War Battlefield." North Carolina Historic Sites. Accessed July 09, 2019. https://historicsites.nc.gov/resources/north-carolina-civil-war/north-ca....