The waters off North Carolina's coast have been called the "Graveyard of the Atlantic" because of the great number of ships that have wrecked there -- thousands since the sixteenth century. Geography, climate, and human activity have all played roles in making this region unusually treacherous to shipping.

By the 1800s, several lighthouses had been built to guide ships safely to shore and around dangerous rocks. In 1848, the U.S. Life-Saving Service was created, with stations along the shoreline to protect life and property from shipwrecks. (The Life-Saving Service eventually became part of the Coast Guard.) In colonial times, though, mariners were left to fend for themselves, relying on hand-drawn maps, descriptions of the coastline, and their own experience.

The geography of the coast

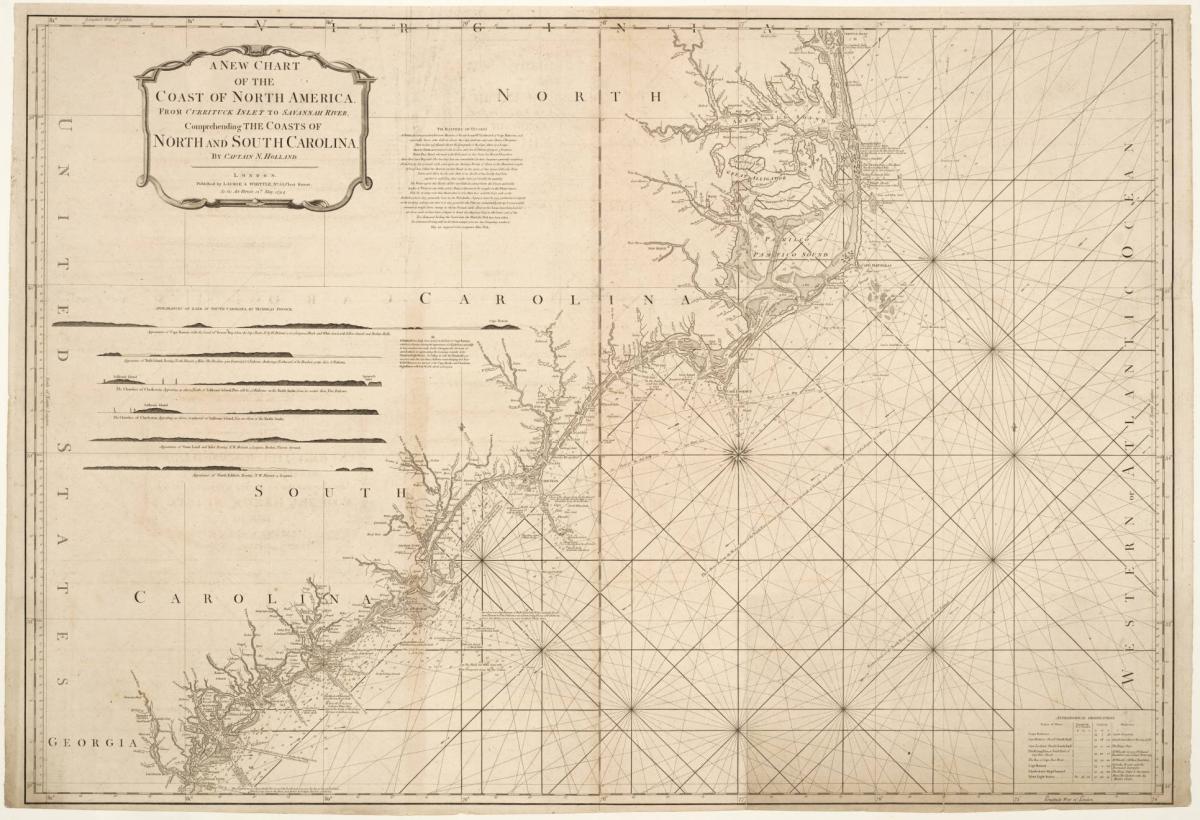

North Carolina has few good harbors in which large ships can safely anchor, but many narrow inlets, small islands, and coastal rivers. The barrier islands, including the Outer Banks, almost completely block access to the mainland. That complicated geography made navigation difficult for ships -- especially in a time when maps were drawn by hand and could be based on inaccurate information. Even worse, storms could close inlets and open new ones, or make once-passable inlets too narrow or too shallow for large ships to navigate.

The map below shows the locations North Carolina's first towns. (Click the markers to see which town is which.) The satellite photos also show just how complicated North Carolina's coastline is. You can see (especially if you zoom in) that each of these early towns is located on the water for ease of transportation, but that some are more easily accessible by water than others. How would ships have reached these towns from the Atlantic Ocean? Can you guess which town grew most slowly in the eighteenth century?

Wreckers

Some residents of the Outer Banks, known as wreckers, made part of their living by scavenging wrecked ships -- or by luring ships to their destruction. In 1860, a writer for Harper's New Monthly Magazine told the story of how Nags Head got its name:

A wilder country than the Banks can not well be imagined. Where it widens to four or five miles there is a little tillage; but, generally speaking, nature has but few encroachments on her primeval rule to complain of. The men may be sweepingly described as combining the vocations of farming, fishing, and wrecking. Their ideas of meam and teemA meam was a temporary shelter built by a traveller (originally, the word meant an aboriginal hut). To teem meant to empty out (though the word is no longer used that way). The phrase "meam and teem" implies theft. Even for the nineteenth-century, though, the writer was being more clever than clear. have been accused of some slight confusion on the subject of stranded property. But by all accounts they are sounder on this point than the coast-people of CornwallCornwall is the region of England farthest to the southwest, which juts out into the Atlantic Ocean. The site of many shipwrecks, it was known as a home of "wreckers," pirates, and smugglers. and Wales. Their kindness and hospitality to wrecked seamen is unfailing and unlimited. Instances have been told us of the surrender, for weeks together, of a shoreman s whole house to a company of such unfortunates without the prospect of compensation. Formerly, practices were attributed to a portion of the Bankers slightly inconsistent with this description. Nags Head derives its name, according to the prevalent etymology, from an old device employed to lure vessels to destruction. A Banks pony was driven up and down the beach at night, with a lantern tied around his neck. The up-and-down motion resembling that of a vessel, the unsuspecting tar An old English nickname for a sailor. would steer for it. Other means of increasing the wreck harvest were resorted to. But the march of moral improvement, let us hope, has abolished them all...

Our own impression is, that Bankers may be found farther inland and farther north who make more money out of wrecks, of one kind or another, and are every way less to he trusted than those of ArabiaThe "wreckers" to be found further inland and north are northern businessmen who take advantage of other people's misfortune -- what later generations would call "robber-barons" or industrial "pirates." The mention of Arabia probably refers to the Barbary pirates, who operated off the coast of North Africa from the late Middle Ages until the early nineteenth century, capturing trading ships and demanding ransom for the return of crews. The United States fought two "Barbary wars" in the early 1800s, after which American ships were typically safe in the region. (The line "to the shores of Tripoli" in the opening of the Marine Hymn comes from action by the U.S. Marine Corps in these wars.). We throw out the idea for what it is worth, and shall be delighted to know that no one of our readers has cause to coincide in our opinion.1

Pirates and privateers

The many hidden inlets and small harbors along North Carolina's coast made excellent hideouts for pirates. The notorious Blackbeard rested his crews and repaired his ships on the Outer Banks.

Although we think of pirates as being lone figures roaming the seas, loyal to none but themselves, many were privateers -- ships authorized by their governments to attack and raid enemy ships. Privateers operated independently, apart from the navy, but were an accepted part of naval warfare from the 1500s to the 1800s. Private investors paid for privateering in hopes of profiting from stolen goods, while governments appreciated the damage they did to enemy commerce.

During the many wars fought between England and Spain from the 1580s to the 1760s, Spanish privateers frequently raided the coast of North Carolina. In 1747, Spanish privateers anchored in Cape Lookout Bight and sent men ashore to capture the town of Beaufort. The local militia turned out and forced the invaders back to their ships.2

Hurricanes

If ships made it past the sand bars, wreckers, and pirates, they still had nature to contend with. Because of its location and climate, North Carolina is frequently subjected to hurricanes.

Tropical cyclones -- the biggest of which we call hurricanes -- form in the tropics and move northward, most often around an area of high atmospheric pressure centered over Bermuda called the Bermuda High. Depending on the size of the Bermuda High in a given summer, hurricanes following this path have a good chance of making landfall in North Carolina. In fact, the point most frequently visited by hurricanes in the entire North Atlantic is just 20 miles off Cape Hatteras!