Rosa Parks would later say of the day that changed her life: “The only tired I was was tired of giving in.” A secondary-school graduate at a time when diplomas were hard to come by for blacks in the South, Parks was active in her local NAACP, a registered voter (another privilege held by few southern blacks), and a respected figure in Montgomery, Alabama. In the summer of 1955, she attended an interracial leadership conference at the Highlander Folk School, a Tennessee institution that trained labor organizers and desegregation advocates. Parks thus knew of efforts to improve the life of African Americans and that she was well-suited to provide a test case should the occasion arise.

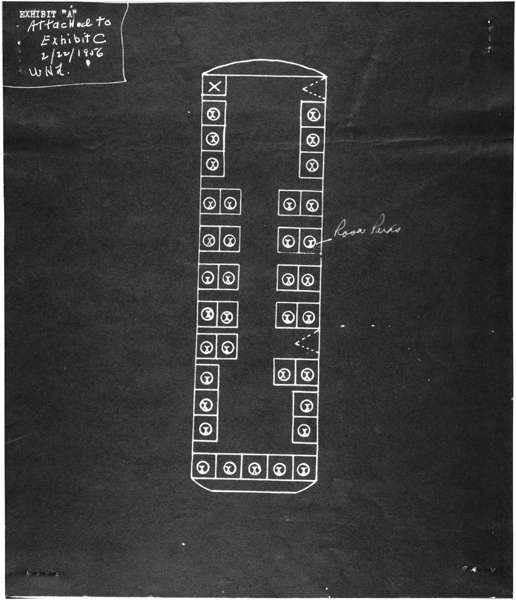

On December 1, 1955, Parks was employed as a seamstress at a local department store. When she rode home from work that afternoon, she sat in the first row of the “colored section” physically almost on the boundary between black and white. When the white seats filled, the driver ordered Parks to give up her seat when another White person boarded the bus. Parks refused. She was arrested, jailed, and ultimately fined $10, plus $4 in court costs. Parks was 42 years old; she had crossed the line into direct political action.

An outraged black community formed the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) to organize a boycott of the city bus system. Partly to forestall rivalries among local community leaders, citizens turned to a recent arrival to Montgomery, the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. The newly-installed pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, King was just 26 years old but he had been born to leadership: His father, the Reverend Martin Luther King Sr., headed the influential Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, was active in the Georgia chapter of the NAACP, and had since the 1920s refused to ride Atlanta’s segregated bus system.

In his first speech to MIA, the younger King told the group:

We have no alternative but to protest. For many years we have shown an amazing patience. We have sometimes given our white brothers the feeling that we liked the way we were being treated. But we come here tonight to be saved from that patience that makes us patient with anything less than freedom and justice.

Under King’s leadership, boycotters organized carpools, while Black taxi drivers charged boycotters the same fare — 10 cents — they would have paid on the bus. By auto, by horse-and-buggy, and even simply by walking, direct, nonviolent political action forced the city to pay a heavy economic price for its segregationist ways.

It also made a national figure of King, whose powerful presence and unsurpassed oratorical skills drew publicity for the movement and attracted support from sympathetic whites, especially those in the North. King, Time magazine later concluded, had “risen from nowhere to become one of the nation’s remarkable leaders of men.”

Even after his house was attacked, King and more than 100 boycotters were arrested for “hindering a bus,” King continued grace and adherence to nonviolent tactics earned respect for the movement. His persistance also discredited the segregationists of Montgomery. When an explosion shook King’s house with his wife and baby daughter inside, it briefly appeared that a riot would ensue. But King calmed the crowd:

We want to love our enemies — be good to them. This is what we must live by, we must meet hate with love. We must love our white brothers no matter what they do to us.

A white Montgomery policeman later told a journalist: “I’ll be honest with you, I was terrified. I owe my life to that... preacher, and so do all the other white people who were there.”

In the end, the desegregation of the Montgomery bus system required not only Rosa Parks’s initiative and bravery, and King’s political leadership, but also an NAACP-style legal effort. As the boycotters braved segregationist opposition, desegregationist attorneys cited the precedent of Brown v. Board of Education in their court challenge to the Montgomery bus ordinance. In November 1956, the Supreme Court of the United States rejected the city’s final appeal, and the segregation of Montgomery buses ended. Thus fortified, the Civil Rights Movement moved on to new battles.