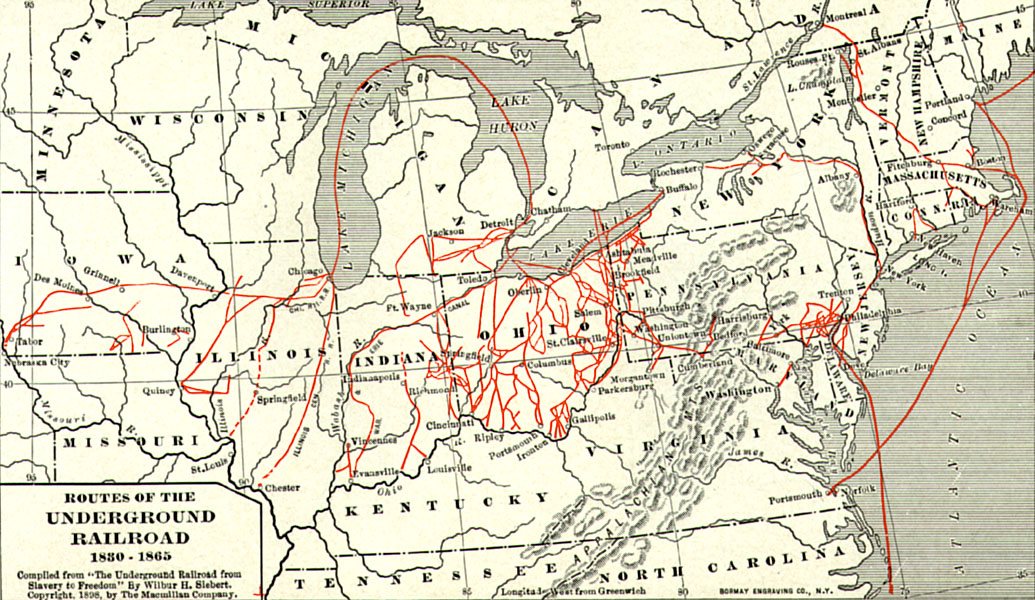

The Underground Railroad was an informal connection of people and homes across the United States that helped freedom seekers -- enslaved people who had escaped their enslavers in the South -- reach safety in the North, Canada, and to a lesser extent Mexico and the Caribbean. It was not an actual railroad but a series of paths that freedom seekers followed from one home to another. In keeping with the idea of a railroad, though, the people who helped the freedom seekers were called “conductors” or “station masters” and their homes were referred to as “stations” or “depots.” Station masters provided enslaved people with food, clothing, and a place to rest. Sometimes a conductor accompanied the freedom seeker, but most often the station master simply provided the freedom seeker with directions to the next station.

Although very few men and women succeeded in escaping slavery, those who did -- and the men and women who helped them -- have captured the imagination of Americans ever since.

Freedom seekers, enslavers, and abolitionists

Enslaved black people had always struggled to be free. Before the Revolution, when all of the colonies permitted slavery, most freedom seekers hid in communities located in swamps, forests, or mountains. These were known as maroon communities. Beginning in the 1770s, northern states abolished slavery, and by the 1830s, slavery was illegal throughout the North and in the British colonies of Canada. By 1810, enslaved people from the South who reached the North, particularly in the cities of New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, could live as free people.

At the same time, federal law had always required free people to return freedom-seeking enslaved people to their enslavers. The 1793 Fugitive Slave Act made it a federal crime for any free person to assist an enslaved person seeking freedom. Hunters hired by their enslavers or working in hope of rewards tracked down freedom seekers and returned them to the South. But many northern states passed laws that overrode or undermined the federal law. They prevented marshals from arresting enslaved people, and they required that any captured freedom seeker must have a trial before a jury to determine whether he or she was truly an enslaved person. Northern juries often sided with freedom seekers regardless of the evidence, effectively granting them emancipation.

Some free people in both the North and the South helped enslaved people escape to the free states. By the 1830s, an abolitionist movement was growing in the North. Men and women who opposed slavery formed societies to raise public awareness of the brutalities of slavery, publishing newspapers and pamphlets, making speeches, and petitioning Congress to abolish slavery. While most abolitionist societies were in the North, a minority of Southerners also believed that slavery was wrong and formed abolitionist societies in their communities.

In this atmosphere, the Underground Railroad was born. Although many people opposed slavery, only a relative handful were devoted enough to the cause to help freedom seekers escape their enslavers. But the abolitionist movement helped to create an environment in the North where freedom seekers could live as free people.

Sectional tension and the Fugitive Slave Act

As the abolition movement grew, though, so did enslavers' anger at what they saw as northern attempts to undermine their property rights. Southern states outlawed abolitionist societies and banned their publications. As part of the Compromise of 1850, the Fugitive Slave Act was toughened. People who harbored freedom seekers could be fined or imprisoned. Freedom seekers were denied all rights under the law; if captured, they were returned immediately to slavery. Thousands of black individuals who had been living as free persons in the North were suddenly at risk of being captured and returned to slavery in the South. In the South, but also in parts of the North where people were sympathetic to slavery, participants in the Underground Railroad faced mob violence if they were found out.

In most of the North, though, the Fugitive Slave Act backfired. Riots broke out in Boston and Philadelphia when hunters of enslaved people arrived and attempted to take freedom seekers, and often free men and women as well, back to the South. Northerners who had turned a blind eye to the realities of slavery now saw them playing out in their own communities. Instead of assuring that more freedom seekers were returned to southern enslavers, the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act rallied more northerners and sympathetic southerners to the cause of freedom seekers. Despite the risks, more people were now willing to assist freedom seekers and find them safe passage to Canada, where they would be beyond the reach of federal marshals and hunters of enslaved people.

Because of the risks, participants kept their activities secret, and almost no one kept records. No single person knew all of the participants; each station master knew only where the next station was, who lived there, and whether there were any other stations in the area. Enslaved people learned of the Underground Railroad through their own informal networks -- from someone they knew who had escaped slavery or from someone who had tried to escape but failed, or through second-hand accounts of people in their neighborhood who might help them to freedom. Because of its informal and secret nature, much about the Underground Railroad is still unknown to historians. Most of what we know comes from stories told after the Civil War, when former enslaved people were finally safe.

Levi Coffin

One North Carolinian, Levi Coffin, dedicated his life to helping enslaved men and women escape slavery. He and his wife Catherine claimed to have helped some 3,000 men and women flee slavery. Because of his efforts, Coffin became known as "the President of the Underground Railroad."

Levi Coffin was born in New Garden, in Guilford County near present-day Greensboro. His family were members of the Society of Friends (Quakers), who opposed slavery. As a child, Coffin was taught that slavery was wrong, and because he lived in North Carolina, he had many opportunities to see the brutalities of slavery at work. As a young man, Coffin had the opportunity to assist freedom seekers.

In 1826, frustrated by life in an enslaving state, Coffin and his wife Catherine left North Carolina and moved to Newport, Indiana (now Fountain City). Indiana was a free state, and Newport was home to a number of Friends as well as freedom seekers. Newport was also bustling town at the intersection of several main roads. The town's centrality and the fact that it was populated by black and white people who opposed slavery made it a key location for men and women fleeing slavery. In his autobiography, Coffin wrote that a new freedom seeker came to his home almost every week.

In 1847, the Coffins moved to Cincinnati and opened up a warehouse so that he could sell goods made by free laborers, and not by enslaved laborers. In Cincinnati, Coffin continued his efforts to help freedom seekers. After the Civil War, Coffin helped raise money in Europe and the American North to help black Americans establish business and farms after their emancipation. He died in Cincinnati in 1877.

Many other men and women also worked tirelessly to help freedom seekers, and some historians argue that Levi Coffin exaggerated his accomplishments and that his fame was not entirely deserved. William Still, a free black man in New Jersey, earned a similar title -- "Father of the Underground Railroad" -- and in his own autobiography, praised the courage of the freedom seekers themselves, who risked far more than the white abolitionists who helped them.

A story of the Underground Railroad

In his autobiography, published after the Civil War, Levi Coffin wrote of his work in helping freedom seekers. He also told how he first became involved in helping enslaved people escape to freedom.