By Douglas O. Linder, B.A., J.D., Professor, School of Law, University of Missouri-Kansas City (2018)

By 1786, Americans recognized that the Articles of Confederation, the foundation document for the new United States adopted in 1777, had to be substantially modified. The Articles gave Congress virtually no power to regulate domestic affairs -- no power to tax, no power to regulate commerce. Without coercive power, Congress had to depend on financial contributions from the states, and they often time turned down requests. Congress had neither the money to pay soldiers for their service in the Revolutionary War or to repay foreign loans granted to support the war effort. In 1786, the United States was bankrupt. Moreover, the young nation faced many other challenges and threats. States engaged in an endless war of economic discrimination against commerce from other states. Southern states battled northern states for economic advantage. The country was ill-equipped to fight a war -- and other nations wondered whether treaties with the United States were worth the paper they were written on. On top of all else, Americans suffered from injured pride, as European nations dismissed the United States as "a third-rate republic."

America's creditor class had other worries. In Rhode Island (called by elites "Rogue Island"), a state legislature dominated by the debtor class passed legislation essentially forgiving all debts as it considered a measure that would redistribute property every thirteen years. The final straw for many came in western Massachusetts where angry farmers, led by Daniel Shays, took up arms and engaged in active rebellion in an effort to gain debt relief.

Troubles with the existing Confederation of States finally convinced the Continental Congress, in February 1787, to call for a convention of delegates to meet in May in Philadelphia "to devise such further provisions as shall appear to them necessary to render the constitution of the Federal Government adequate to the exigencies of the Union."

Across the country, the cry "Liberty!" filled the air. But what liberty? Few people claim to be anti-liberty, but the word "liberty" has many meanings. Should the delegates be most concerned with protected liberty of conscience, liberty of contract (meaning, for many at the time, the right of creditors to collect debts owed under their contracts), or the liberty to hold property (debtors complained that this liberty was being taken by banks and other creditors)? Moreover, the cry for liberty could mean two very different things with respect to the slave issue -- for some, the liberty to own slaves needed protection, while for others (those more able to see through black eyes), liberty meant ending the slavery.

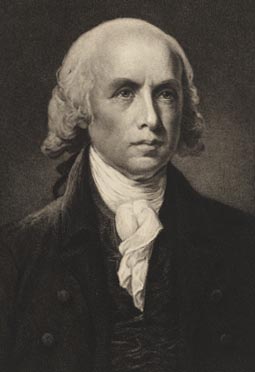

On May 25, 1787, a week later than scheduled, delegates from the various states met in the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia. Among the first orders of business was electing George Washington president of the Convention and establishing the rules -- including complete secrecy concerning its deliberations -- that would guide the proceedings. (Several delegates, most notably James Madison, took extensive notes, but these were not published until decades later.)

The main business of the Convention began four days later when Governor Edmund Randolph of Virginia presented and defended a plan for new structure of government (called the "Virginia Plan") that had been chiefly drafted by fellow Virginia delegate, James Madison. The Virginia Plan called for a strong national government with both branches of the legislative branch apportioned by population. The plan gave the national government the power to legislate "in all cases in which the separate States are incompetent" and even gave a proposed national Council of Revision a veto power over state legislatures.

Delegates from smaller states, and states less sympathetic to broad federal powers, opposed many of the provisions in the Virginia Plan. Charles Pinckney of South Carolina asked whether proponents of the plan "meant to abolish the State Governments altogether." On June 14, a competing plan, called the "New Jersey Plan," was presented by delegate William Paterson of New Jersey. The New Jersey Plan kept federal powers rather limited and created no new Congress. Instead, the plan enlarged some of the powers then held by the Continental Congress. Paterson made plain the adamant opposition of delegates from many of the smaller states to any new plan that would deprive them of equal voting power ("equal suffrage") in the legislative branch.

Over the course of the next three months, delegates worked out a series of compromises between the competing plans. New powers were granted to Congress to regulate the economy, currency, and the national defense, but provisions which would give the national government a veto power over new state laws was rejected. At the insistence of delegates from southern states, Congress was denied the power to limit the slave trade for a minimum of twenty years and slaves -- although denied the vote and not recognized as citizens by those states -- were allowed to be counted as 3/5 persons for the purpose of apportioning representatives and determining electoral votes. Most importantly, perhaps, delegates compromised on the thorny issue of apportioning members of Congress, an issue that had bitterly divided the larger and smaller states. Under a plan put forward by delegate Roger Sherman of Connecticut ("the Connecticut Compromise"), representation in the House of Representatives would be based on population while each state would be guaranteed an equal two senators in the new Senate.

By September, the final compromises were made, the final clauses polished, and it came time to vote. In the Convention, each state -- regardless of its number of delegates -- had one vote, so a state evenly split could not register a vote for adoption. In the end, thirty-nine of the fifty-five delegates supported adoption of the new Constitution, barely enough to win support from each of the twelve attending state delegations. (Rhode Island, which had opposed the Convention, sent no delegation.) Following a signing ceremony on September 17, most of the delegates repaired to the City Tavern on Second Street near Walnut where, according to George Washington, they "dined together and took cordial leave of each other."

Citation:

Linder, Douglas O. “The Constitutional Convention of 1787,” Exploring Constitutional Law, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law. http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/conlaw/convention1787.html