Black Americans became increasingly restive in the postwar years. During the war they had challenged discrimination in the military services and in the work force, but their contributions were largely ignored by white politicians and business owners. Millions of Black Americans had left Southern farms for Northern cities, where they hoped to find better jobs in what is known as The Great Migration. With small amounts of capital earned as tenant farmers or sharecroppers, many Black migrants could not afford adequate housing. Instead, they could afford crowded conditions in urban slums. Now, Black service members returned home, many intent on rejecting second-class citizenship.

Jackie Robinson pushed imposed racial boundaries in 1947 when he broke baseball’s color line and began playing in the major leagues. A member of the Brooklyn Dodgers, he was often harassed and discriminated against by opponents and teammates as well. But an outstanding first season led to his acceptance and eased the way for other Black players, who now left the leagues of Black players to which they had been confined.

Government officials, and many other Americans, discovered the connection between racial problems and Cold War politics. As the political and military leader of the West, the United States sought support in Africa and Asia. Discrimination at home impeded the effort to court allies in other parts of the world.

Harry Truman supported the early civil rights movement. He personally believed in political equality, though not in social equality, and recognized the growing importance of the Black American urban vote. When informed in 1946 of a span of lynchings and anti-Black violence in the South, he appointed a committee on civil rights to investigate discrimination. Its report, To Secure These Rights, issued the next year, documented Black Americans’ second-class status in American life and recommended numerous federal measures to secure the rights guaranteed to all citizens.

Truman responded by sending a 10-point civil rights program to Congress. Southern Democrats in Congress blocked its enactment. A number of the angriest, led by Governor Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, formed a States Rights Party to oppose the president in 1948. Truman thereupon issued an executive order barring discrimination in federal employment, ordered equal treatment in the armed forces, and appointed a committee to work toward an end to military segregation, which was largely ended during the Korean War.

Black Southerners in the 1950s still enjoyed few, if any, civil and political rights. In general, they could not vote. Despite the 15th and 19th Amendments protecting the rights of all Americans to vote, Black people who tried to register (and subsequently vote) faced the likelihood of beatings, loss of job, loss of credit, or eviction from their land. State laws, like grandfather clauses and literacy tests, supported the white-only voting processes. Lynchings still occurred. Jim Crow laws enforced segregation of the races in streetcars, trains, hotels, restaurants, hospitals, recreational facilities, and employment.

Desegregation

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) took the lead in efforts to overturn the judicial doctrine, established in the Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896, that segregation of Black and white students was constitutional if facilities were “separate but equal.” That decree had been used for decades to sanction rigid segregation in all aspects of Southern life, where facilities were seldom, if ever, equal.

Black Americans achieved their goal of overturning Plessy in 1954 when the Supreme Court – presided over by an Eisenhower appointee, Chief Justice Earl Warren – issued its Brown v. Board of Education ruling. The Court declared unanimously that “separate facilities are inherently unequal,” and decreed that the “separate but equal” doctrine could no longer be used in public schools. A year later, the Supreme Court demanded that local school boards move “with all deliberate speed” to implement the decision.

Eisenhower, although sympathetic to the needs of the South as it faced a major transition, nonetheless acted to see that the law was upheld in the face of massive resistance from many white Southerners. A major crisis erupted in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957, when Governor Orval Faubus attempted to block a desegregation plan calling for the admission of nine black students to the city’s previously all-white Central High School. After futile efforts at negotiation, the president sent federal troops to Little Rock to enforce the plan.

Governor Faubus responded by ordering the Little Rock high schools closed down for the 1958-59 school year. However, a federal court ordered them reopened the following year. They did so in a tense atmosphere with a tiny number of Black students. Thus, school desegregation proceeded at a slow and uncertain pace throughout much of the South.

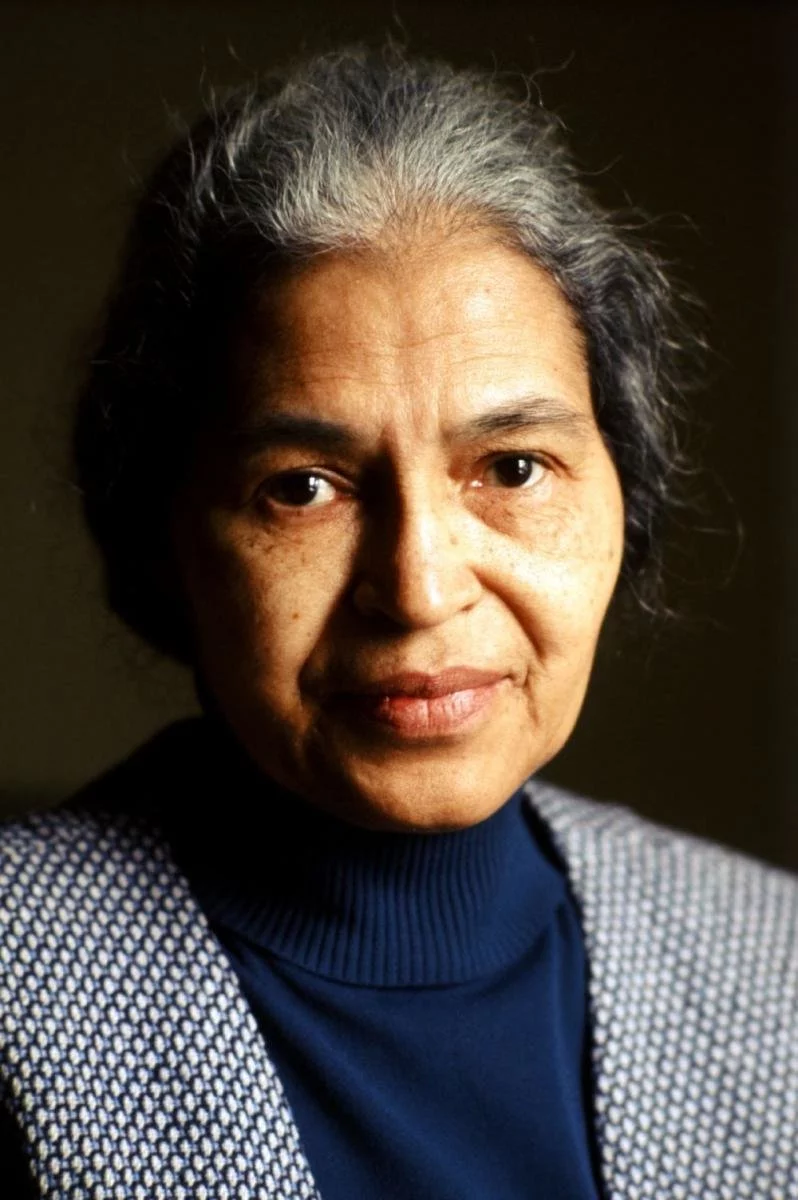

Another milestone in the civil rights movement occurred in 1955 in Montgomery, Alabama. Rosa Parks, a 42-year-old Black seamstress who was also secretary of the state chapter of the NAACP, sat down in the front of a bus in a section reserved by law and social custom for whites. Ordered to move to the back, she refused. Police came and arrested her for violating the segregation statutes. Black activist leaders, who had been waiting for just such a case, organized a boycott of the bus system.

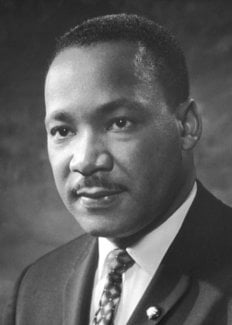

Martin Luther King Jr., a young minister of the Baptist church where the Black Americans congregated, became a spokesman for the protest. “There comes a time,” he said, “when people get tired … of being kicked about by the brutal feet of oppression.” King was arrested, as he would be again and again. He was also threatened with physical violence; a bomb even damaged the front of his house. But Black people in Montgomery sustained the boycott. About a year later, the Supreme Court affirmed that bus segregation, like school segregation, was unconstitutional. The boycott ended. The civil rights movement had won an important victory – and discovered its most powerful successful leader in Martin Luther King Jr.

Black Americans also sought to secure their voting rights. Although the 15th and 19th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution guaranteed the rights to vote for non-white men, many states had found ways to circumvent the law. The states would impose a poll (”head”) tax or a literacy test – typically much more stringently interpreted for Black voters – to prevent poor Black voters with little education from voting. Eisenhower, working with Senate majority leader Lyndon B. Johnson, lent his support to a congressional effort to guarantee the vote. The Civil Rights Act of 1957, the first such measure in 82 years, marked a step forward, as it authorized federal intervention in cases where Black Americans were denied the chance to vote. Yet loopholes remained, and so activists pushed successfully for the Civil Rights Act of 1960, which provided stiffer penalties for interfering with voting, but still stopped short of authorizing federal officials to register Black Americans.

Relying on the efforts of Black activists themselves, the civil rights movement gained momentum in the postwar years. With civil protest and demands of better conditions from Black activists, and with successful legislation through the Supreme Court and through Congress, civil rights supporters had created the groundwork for a dramatic yet peaceful “revolution” in American race relations in the 1960s.

Passage derived from Outline of U.S. History. Edited by Michael Jay Friedman, et. al. U.S. Department of State: Bureau of International Information Programs. 2011. https://archive.org/details/OutlineOfUSHistory/page/n1. Additional edits provided by SLNC Government and Heritage Library, 2023.